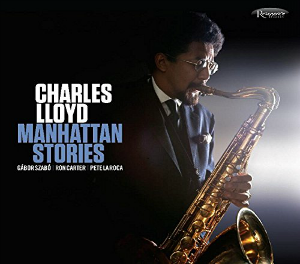

In 1965, the Beatles, Rolling Stones and other British rock groups were steadily siphoning away the audiences from all other types of music. Jazz was still hanging on, both in straight-ahead and avant-garde forms, and there were plenty of fine musicians producing great music. Narrowing the field to just the tenor saxophonists, fans could hear (on records if not always in person) John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Sonny Rollins, Dexter Gordon, Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson, Stan Getz, and a musician whose star had been rising for the past half-decade, Charles Lloyd. Lloyd’s public breakthrough came in 1967 with his live recording of “Forest Flower” (with a stellar quartet featuring Keith Jarrett, Cecil McBee and Jack DeJohnette), but he had already recorded “Forest Flower” twice before, once with his former employer, Chico Hamilton, and with his own quartet on his first Columbia album, “Discovery”. Lloyd was the musical director for Hamilton’s underrated early-to-mid 1960s band, and in mid-1965, when he left Hamilton for a spot in Cannonball Adderley’s sextet, he performed two live performances with his own group that are now part of the Resonance album, “Manhattan Stories”.

In 1965, the Beatles, Rolling Stones and other British rock groups were steadily siphoning away the audiences from all other types of music. Jazz was still hanging on, both in straight-ahead and avant-garde forms, and there were plenty of fine musicians producing great music. Narrowing the field to just the tenor saxophonists, fans could hear (on records if not always in person) John Coltrane, Albert Ayler, Sonny Rollins, Dexter Gordon, Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson, Stan Getz, and a musician whose star had been rising for the past half-decade, Charles Lloyd. Lloyd’s public breakthrough came in 1967 with his live recording of “Forest Flower” (with a stellar quartet featuring Keith Jarrett, Cecil McBee and Jack DeJohnette), but he had already recorded “Forest Flower” twice before, once with his former employer, Chico Hamilton, and with his own quartet on his first Columbia album, “Discovery”. Lloyd was the musical director for Hamilton’s underrated early-to-mid 1960s band, and in mid-1965, when he left Hamilton for a spot in Cannonball Adderley’s sextet, he performed two live performances with his own group that are now part of the Resonance album, “Manhattan Stories”.

The first disc was recorded by Resonance’s owner George Klabin when he was the head of jazz programming at WKCR-FM, Columbia University’s radio station. Like the Bill Evans set released on Resonance a few years ago, the Lloyd performance was recorded live for possible broadcast on the station. Klabin caught Lloyd at Judson Hall as part of cellist Charlotte Moorman’s Festival of the Avant-Garde. While the recording balance finds Lloyd a little distant (and that may be due to the saxophonist’s constant swaying in the heat of improvisation), there’s no missing the fire in his playing. It’s easy to hear the essence of the Coltrane sound in Lloyd’s tone, but it’s clear that Lloyd was finding his own direction. Lloyd’s quartet features his closest musical compatriot at the time, Hungarian guitarist Gábor Szabó, plus the unbeatable rhythm section of Ron Carter and Pete La Roca. On the opening track, “Sweet Georgia Bright”, Szabó refrains from comping for himself or for the other soloists, leaving the backgrounds in the harmonically open atmosphere of bass and drums. There is occasional interplay between Lloyd and Szabó, but for the most part, the main soloist is allowed to have the spotlight alone. On “How Can I Tell You”, an original ballad Lloyd dedicated to Billie Holiday, the setting is much more traditional. While there are still bits of interplay between saxophone and guitar, Szabó also provides some chords behind Lloyd’s melody and improvisation. Although Szabó is pictured with an acoustic guitar, it sounds like he’s playing electric, and his tone is quite brittle and tinny, denying this lovely piece the warmth that it deserves. Carter plays an extraordinary solo on this track, and he plays superbly crafted counterlines behind Lloyd near the end of the performance. Lloyd switches to flute for the final track, Szabó’s complex original “Lady Gabor”. Here, Szabó and the rhythm build an exciting 3/4 vamp behind Lloyd’s improvisation. Szabó plays a harmonically daring solo in the more aggressive second section, and while Carter is playing a repeating ostinato, it still sounds like a commentary to Szabó’s solo. Lloyd’s second flute solo is fascinating, using non-traditional techniques to bring out overtones and to explore the percussive element of the instrument by flapping the keys.

The second disc comes from a tape in Lloyd’s private collection. It was recorded at Slug’s, a rather notorious club in Greenwich Village, around the same time as the Judson Hall concert, and with the same quartet. Like the Judson Hall concert, the set at Slugs’ contains three long tracks (including a repeat of “Lady Gabor”). And that’s about where the similarities end. Slugs’ was also a neighborhood bar, and there’s quite a bit of background chatter. While the recording was probably made with a single microphone, the balance between the instruments is actually a little better, despite the occasional bit of distortion and feedback. Lloyd seems a little more reserved on this date, while Szabó takes considerable chances, and Carter and La Roca are quite turbulent both as a team and as soloists. The opening “Slugs’ Blues” was written especially for this performance, and near the end, there’s another great dual improvisation between Lloyd and Szabó, this one sounding like a distant cousin of Fats Waller’s “Jitterbug Waltz”! The opening groove on the Slugs’ version of “Lady Gabor” is much funkier than Judson, and the second section moves much faster to less effect. Lloyd shakes a maraca in a cross-rhythm to the rhythm section’s vamp while Szabó improvises an aggressive solo. Lloyd also takes a different approach here, riding the groove and raising the intensity while adding occasional elements of polytonality, and leaving out the overtones and key flapping. The final piece, “Dream Weaver” was recorded in 1966 with Jarrett, McBee and DeJohnette as the title track of Lloyd’s first Atlantic album. The Latin rock groove indicates that Lloyd was aware of what was happening on the larger music scene, and there seems to be a real difference in the way the band approaches this piece, as opposed to the other songs on this set. There’s less interplay and there’s less flexibility to the rhythm. Still, Lloyd seems very comfortable with the groove, and he plays an energetic solo to cap off the set.

It is quite fortuitous that these two sets are being presented together. Apart from the common personnel (and these are the only recordings by this particular edition of Lloyd’s quartet), the two sets contrast well with each other, showing the strengths of each setting. These recordings also represent Szabó’s final collaborations with Lloyd (save a pair of 1972 reunions). Finally, the closing track offers an early view of Lloyd’s next musical direction, and bridges the gap between the better-known Lloyd performances of 1967 and his formative recordings of the years before. George Klabin has again provided the jazz world with historically important music that enlightens our understanding of jazz. Let us hope that he continues to find and release these truly remarkable albums.