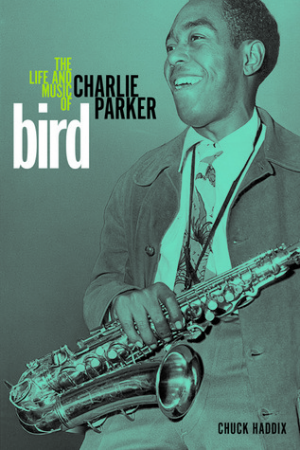

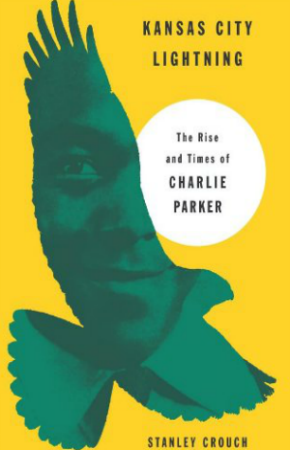

Imagine hearing recordings of the same song performed by pianists Art Tatum and Jimmy Yancey. The common song would doubtlessly be a blues (Yancey played little else) and as such, it would provide the basis for a wide variety of interpretations. Tatum would dazzle the listener with his overwhelming technique and his subtle reworking of the harmony, but Yancey could touch the listener with his emotionally spare melodies and his surprising bass lines. There are no common tunes in the Tatum and Yancey discographies to enable such a comparison, but in back-to-back readings of two new Charlie Parker biographies, I felt the same sensation of common theme and wildly disparate variations. Like the hypothetical blues above, Parker’s life—so clouded with hyperbole, legend and half-truths—offers many options for the biographer. While Chuck Haddix’s “Bird: The Life and Music of Charlie Parker” (University of Illinois Press) and Stanley Crouch’s “Kansas City Lightning” (Harper Collins) touch upon many of the same facts about Parker, the books are considerably different in tone, style and scope.

Imagine hearing recordings of the same song performed by pianists Art Tatum and Jimmy Yancey. The common song would doubtlessly be a blues (Yancey played little else) and as such, it would provide the basis for a wide variety of interpretations. Tatum would dazzle the listener with his overwhelming technique and his subtle reworking of the harmony, but Yancey could touch the listener with his emotionally spare melodies and his surprising bass lines. There are no common tunes in the Tatum and Yancey discographies to enable such a comparison, but in back-to-back readings of two new Charlie Parker biographies, I felt the same sensation of common theme and wildly disparate variations. Like the hypothetical blues above, Parker’s life—so clouded with hyperbole, legend and half-truths—offers many options for the biographer. While Chuck Haddix’s “Bird: The Life and Music of Charlie Parker” (University of Illinois Press) and Stanley Crouch’s “Kansas City Lightning” (Harper Collins) touch upon many of the same facts about Parker, the books are considerably different in tone, style and scope.

Haddix’s book falls under the typical academic biography model. Written in a clear, straight-forward style, it is copiously annotated and carefully delineates many of the mileposts in Parker’s life. He supplements the standard Parker biographies by Robert Reisner, Ross Russell, Gary Giddins and Carl Woideck with his own interviews with Parker’s former boss, Jay McShann and research into Parker’s school and census records. He discusses Parker’s family history, his upbringing in Kansas City, his long musical apprenticeship, his artistic successes and personal differences with Dizzy Gillespie, his roller-coaster private life, his addiction to drugs, and his final decline. Crouch’s book is part of a proposed two-volume set, so “Kansas City Lightning” only deals with Parker’s life up to 1942. Crouch’s florid writing style is a curious mixture of William Faulkner and black street slang, and the book reads more like a novel than a standard biography. There are no footnotes, but there is a page-by-page source listing at the back of the book. Most of the sources refer to Crouch’s personal interviews with Parker’s family and colleagues. Crouch provides much more detail regarding Parker’s life in Kansas City, but it is clouded with imagined dialogue and long rhapsodic passages which purport to reflect Parker’s inner feelings. He also questions many of the established stories about Parker including his chili house revelation and his dish washing job that let him hear Tatum every night.

Crouch’s free-form style brings on its own problems. His narrative goes off on tangents with the slightest impulse. When Parker hoboes out of Kansas City on a freight train, Crouch launches a historical fantasy linking the stories of Western America rail travel, Geronimo, Chinese rail  workers and Parker’s love of Chinese food (probably not authentic Chinese cuisine, but American chop suey). Parker happened to propose to his childhood sweetheart on the night of the Joe Louis/Max Schmeling boxing match, and this sets off an 8-page discussion of Joe Louis and Jack Johnson. Again, the connection to Parker’s story is extremely weak, as Crouch notes that Johnson owned the club that became the Cotton Club, site of Duke Ellington’s big breakthrough, and that Parker was very impressed with Ellington’s stage manner. Even when the subject matter is closer to Parker, such as the history of music in Kansas City, Crouch goes back much further than necessary, starting that section with the career of the 19th century bandleader Frank Johnson! With each of these tangents (including discussions of George Armstrong Custer, Coronado and D.W. Griffith) the reader is left wondering “How did I get here?”, “How did Crouch get here?” and “What does this have to do with Charlie Parker?”.

workers and Parker’s love of Chinese food (probably not authentic Chinese cuisine, but American chop suey). Parker happened to propose to his childhood sweetheart on the night of the Joe Louis/Max Schmeling boxing match, and this sets off an 8-page discussion of Joe Louis and Jack Johnson. Again, the connection to Parker’s story is extremely weak, as Crouch notes that Johnson owned the club that became the Cotton Club, site of Duke Ellington’s big breakthrough, and that Parker was very impressed with Ellington’s stage manner. Even when the subject matter is closer to Parker, such as the history of music in Kansas City, Crouch goes back much further than necessary, starting that section with the career of the 19th century bandleader Frank Johnson! With each of these tangents (including discussions of George Armstrong Custer, Coronado and D.W. Griffith) the reader is left wondering “How did I get here?”, “How did Crouch get here?” and “What does this have to do with Charlie Parker?”.

While Crouch spends a great deal of time on Parker’s KC home life, Haddix gives us more background on Parker’s musical experiences, such as his gigs with childhood bands, his first professional jobs and his relationships with people in the music business. Through Haddix’s narrative, we get an objective feel for each episode’s atmosphere. When discussing Parker’s recordings, he provides readable analysis that communicates the important points without delving into deep musical jargon. Unfortunately, Haddix leaves out or glosses over several of Parker’s finest discs. While “Parker’s Mood” is used as a chapter title, there is no discussion of this seminal recording. The Dial recordings from Los Angeles are all duly noted, but the New York Dial sessions—which feature Parker’s working quintet and include some of his finest ballad readings—are written off as a safeguard against the 1948 recording strike. Crouch’s book cuts off just as Parker’s recording career is starting, but his final pages include a flowery description of Parker’s first recording, the 1940 private recording of “Honey and Body” (an unaccompanied medley of “Honeysuckle Rose” and “Body and Soul” that Haddix never mentions). Crouch doesn’t really write about the music, preferring to speculate about Parker’s mental state at the time. Had Crouch consulted Carl Woideck’s book, he would have found that Parker included a direct quote of Roy Eldridge in that solo, and that would have bolstered his earlier argument about Eldridge’s influence on the young saxophonist.

Like our hypothetical comparison from the beginning of this review, it’s easier to determine a preference between these two biographies than to declare which one is better. Haddix’s book is very informative and well-paced. It’s easy to find important facts within the volume, and had Haddix devoted more time to the recordings, his book may have become the definitive biography of Bird. Crouch’s book is much more dense and frustrating, but the rich details make Parker’s story come alive. Some of the material seems under-researched (like the supposed existence of a 1940 Harlan Leonard jukebox soundie with Bird on clarinet), but he has also uncovered elements of Parker’s life that give us a better understanding of his demeanor. It remains for Crouch’s second volume to illuminate the rest of Charlie Parker’s story.