Sometime between mid-September and mid-October 1961, producer Bob Thiele went to the Copacabana in New York where Peggy Lee was performing. Thiele’s main purpose in visiting the club was to talk to Lee’s arranger and conductor, Benny Carter. Thiele explained that he had just started working for a new record label called Impulse, and that he had plenty of John Coltrane recordings ready to release, but wanted to have more straight-ahead jazz in his catalogue. Brimming with enthusiasm, Thiele said that Carter’s old friend Coleman Hawkins was in town, as was Jo Jones, and wouldn’t it be great to have all of you guys playing together, etc. Carter recalled that he hated to interrupt Thiele’s pitch, but he had to explain that he hadn’t played his alto sax in 8 months, and had no arrangements ready to record. Thiele was undeterred, saying, “Oh, Benny, you’re a pro; you can make it happen”. Carter did just that, getting his horn sent to his hotel room, and writing eight superb charts for four saxophones and rhythm in a single night.

Sometime between mid-September and mid-October 1961, producer Bob Thiele went to the Copacabana in New York where Peggy Lee was performing. Thiele’s main purpose in visiting the club was to talk to Lee’s arranger and conductor, Benny Carter. Thiele explained that he had just started working for a new record label called Impulse, and that he had plenty of John Coltrane recordings ready to release, but wanted to have more straight-ahead jazz in his catalogue. Brimming with enthusiasm, Thiele said that Carter’s old friend Coleman Hawkins was in town, as was Jo Jones, and wouldn’t it be great to have all of you guys playing together, etc. Carter recalled that he hated to interrupt Thiele’s pitch, but he had to explain that he hadn’t played his alto sax in 8 months, and had no arrangements ready to record. Thiele was undeterred, saying, “Oh, Benny, you’re a pro; you can make it happen”. Carter did just that, getting his horn sent to his hotel room, and writing eight superb charts for four saxophones and rhythm in a single night.

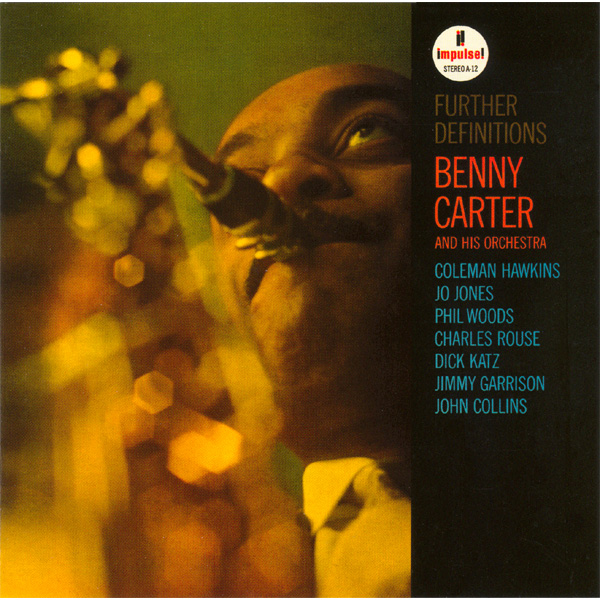

The resulting album was called “Further Definitions” and it stands as one of Carter’s greatest recordings. The personnel mixed players from two generations: Carter and Phil Woods played alto, Hawkins and Charles Rouse were the tenors, and the rhythm section had Dick Katz on piano, John Collins on guitar, Jimmy Garrison on bass and Jones on drums. Despite the age gaps, the group plays with astounding cohesiveness. The rhythm section locks into solid grooves on every number, and the saxes—all of whom had played in big bands—phrased together as if they’d been playing next to each other for years. The recorded sound is breathtaking, with close-miked horns in the forefront and clear crisp rhythm behind. There’s a palpable excitement as the band lights into Carter’s inventive arrangements, and the solos are inspired throughout.

Unlike many of the abstract album titles from Impulse’s early years, “Further Definitions” actually describes the album’s concept. Four of the eight tunes are updates of classic swing recordings. Two of the tunes, “Honeysuckle Rose” and “Crazy Rhythm” were recorded by Hawkins and Carter at a 1937 all-star date in Paris. Like “Further Definitions”, the instrumentation was four saxes and rhythm (Stephane Grappelli and Django Reinhardt played piano and guitar, respectively) and the “Further Definitions” versions are reasonable recreations of Carter’s original arrangements. The 1937 version of “Crazy Rhythm” became famous among jazz fans because of Django’s vocal encouragement to Hawkins (“go on, go on”) as the saxophonist was finishing his chorus. Hawkins did indeed go on for another chorus, and whatever Carter had written for the final chorus was immediately discarded so that the record would not go over the three-minute time limit. On “Further Definitions”, there is a brief recapitulation of the melody at the coda, but there is no way to know if that was what Carter had written back in 1937. “Cottontail” includes an excellent reconstruction of the sax soli chorus from Duke Ellington’s 1940 recording, and on “Body and Soul”, Carter orchestrates the first eight bars of Hawkins’ 1939 solo recording. In the late 50s, Hawkins was developing a new approach for his solo on “Body and Soul”. There is a rare live recording from the 1959 Playboy Jazz Festival that shows him formulating some of the ideas. By the time he recorded it on “Further Definitions” the solo had become a well-tuned statement, every bit as stunning as his 1939 improvisation.

The remaining four arrangements were an old favorite, “Cherry”, a recent Quincy Jones composition, “The Midnight Sun Will Never Set” and two Carter originals, “Doozy” and “Blue Star”. “Cherry” swings along mightily with energetic solos and a kicking set of ensemble variations. The Jones piece is a gorgeous ballad previously recorded by Count Basie, and if not for “Blue Star”, it would have been the best cut on the record. But “Blue Star” (later re-titled “Evening Star” to accommodate lyrics) is the stunner. Carter’s solo is a masterpiece of delicate filigree and elegant improvisation, and it is followed by an extraordinary ensemble variation. Woods made the suggestion that the rhythm section play double-time during this chorus and that accentuates the brilliant flurries of sixteenth notes that mark Carter’s ensemble variation. The other Carter original is a blues called “Doozy”. It is a swinging closer for the original album, but the CD reissue also includes Carter’s 1966 follow-up “Additions to Further Definitions”, and for that album, Carter re-structured “Doozy” into an AABA blues plus bridge form (12 + 12 + 8 + 12). The later album, recorded in LA with saxophonists Bud Shank, Buddy Collette, Teddy Edwards and Bill Perkins, and Ray Brown anchoring the rhythm section, swings as much as the earlier album, and Carter’s compositions and arrangements are as spectacular as ever.

In 1983, I visited Carter in his home in the Hollywood Hills. I had a copy of the LP reissue of “Further Definitions” with me, which I wanted Carter to autograph for a friend of mine. Carter was extremely gracious, and related many of the stories about the album included above. The week after our visit, he was on his way back to New York to perform a tribute to Coleman Hawkins at Carnegie Hall, and the program included several of the charts from “Further Definitions”. He was quite surprised at my enthusiasm for the album, and when I asked him if the arrangements had ever been published, he said “Do you really think they’re that good?” He showed me his part for “Blue Star” and as I looked at the yellowed music paper, the sounds of the arrangement raced into my head. I don’t think he ever got around to publishing the arrangements, but indeed they were that good.