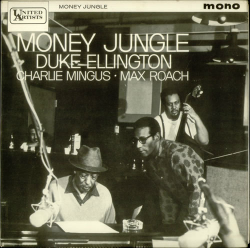

All-star jazz albums tend to be less than the sum of their parts, but Duke Ellington had better luck than most. Guest stars, including Bing Crosby, Tommy Dorsey, and Dizzy Gillespie, had recorded with his band without compromising Ellington’s independent character, and the Ellington band had even held their own when recording with the full Count Basie Orchestra. In 1962, Ellington was between recording contracts, and many of his sessions that year found him leading small groups. On August 18, he recorded a septet date with Coleman Hawkins, and on September 26, he cut a memorable album with John Coltrane. But nine days before the Coltrane date, he recorded “Money Jungle“, a trio album which pitted him against Charles Mingus and Max Roach. Combining three of the most powerful voices in jazz was a brilliant idea, and the raw energy of the music they created was less akin to sparks flying and more like landmines exploding.

All-star jazz albums tend to be less than the sum of their parts, but Duke Ellington had better luck than most. Guest stars, including Bing Crosby, Tommy Dorsey, and Dizzy Gillespie, had recorded with his band without compromising Ellington’s independent character, and the Ellington band had even held their own when recording with the full Count Basie Orchestra. In 1962, Ellington was between recording contracts, and many of his sessions that year found him leading small groups. On August 18, he recorded a septet date with Coleman Hawkins, and on September 26, he cut a memorable album with John Coltrane. But nine days before the Coltrane date, he recorded “Money Jungle“, a trio album which pitted him against Charles Mingus and Max Roach. Combining three of the most powerful voices in jazz was a brilliant idea, and the raw energy of the music they created was less akin to sparks flying and more like landmines exploding.

The recording was made for United Artists, to which Mingus was under contract. In the most famous story about the album, the tension between Mingus and Roach grew so thick that Mingus walked out of the recording session, apologizing to Duke on the way out of the studio. Ellington followed Mingus to the elevator, and calmly reminded the bassist of the impressive advertising campaign that United Artists had just launched for the bassist. Ellington said, “If Columbia had done that for me, I’ll still be with them.” With that, the bassist and pianist went back to work. On Blue Note’s 1987 CD reissue, the tracks are placed in session order, and one can easily hear the tension building during the uptempo numbers. Even after the group moved to lighter works, the tension picked up as before when they resumed working on faster tunes. The title track represents the apex of the group’s inner tension, with Mingus plucking the strings with his fingernails, Roach firing up the music with polyrhythms and Ellington laying down highly dissonant chords. I suspect that Mingus’ walk-out happened after this track was recorded, since the rest of the date, is rather subdued. “Backward Country Boy Blues” is the most interesting of these late tracks, as it features Mingus and Ellington as equal melodic voices. On the false start of that tune, Ellington verbally encourages Mingus after a particularly soulful opening phrase.

The album is not very consistent. A total of fifteen tracks were recorded and over half of them didn’t make it to the original LP. Most of the music was written by Ellington specifically for the date, and never recorded elsewhere. Yet, the energetic performances of “REM Blues” and “Switch Blade” were passed over in favor of less interesting versions of the Ellington classics “Solitude”, “Warm Valley” and “Caravan”. Of the remaining originals, “Wig Wise” has a bitonal flavor, “Very Special” is a blues with a solid if standard groove (it was the first track recorded), “A Little Max” (aka “Parfait”) is a charming Ducal bonbon that fails to fully take shape, and “Fluerette Africaine” (probably the most covered piece from the session) contains an atmospheric episode where none of the musicians explicitly state the ground beat. On a Blindfold Test for Downbeat magazine, Miles Davis was played “Solitude” from this album, and dismissed the effort, saying that Duke’s style was incompatible with that of Mingus and Roach. Yet, the title track, “Fluerette Africaine” and several of the originally unissued tracks show that Ellington was quite effective in this challenging company.

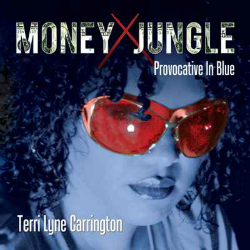

As it turns out, tribute albums can be just as risky as all-star dates. Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of “Money Jungle” is a new version by Terri Lyne Carrington, subtitled “Provocative in Blue” (Concord). The core trio of the band, featuring Carrington’s drums with pianist Gerald Clayton and bassist Christian McBride, is an amazing and powerful group, and any live dates spurred by this album should be very exciting. Unfortunately, Carrington’s version is not a trio album. The album has been loaded with guest artists, and while each of these artists are very talented, they really have no place on this album. It’s great to have Clark Terry on the album, but his comic “mumbles” singing (which came from his experience with the “Tonight Show” band, not Ellington) only detracts from the beauty of “Fluerette Africaine”. Similarly, Lizz Wright‘s wordless vocals on “Backward Country Boy Blues”, Nir Felder‘s sitar-like guitar on Carrington’s original “Grass Roots” and Shea Rose‘s pseudo-sexy reading of the Ellington poem “Music” on “REM Blues” do nothing to enhance the music. And when Tia Fuller, Antonio Hart, and Robin Eubanks join in on a collective improvisation during the trio’s version of “Switch Blade”, the horns just get in the way of a fascinating trio exploration. When the trio plays alone, as on “Wig Wise” and “Very Special”, the album succeeds in getting the feel of the original album, even though Carrington’s trio creates intensity in an entirely different way than Ellington, Mingus and Roach. When it veers away with over-produced sounds, funk grooves and political soundbites, the timelessness of the original music is lost. Carrington’s previous album, “The Mosaic Project” was a triumphant celebration of women jazz musicians; “Money Jungle” certainly deserves the same praise, but perhaps it’s best to leave the original alone.

pianist Gerald Clayton and bassist Christian McBride, is an amazing and powerful group, and any live dates spurred by this album should be very exciting. Unfortunately, Carrington’s version is not a trio album. The album has been loaded with guest artists, and while each of these artists are very talented, they really have no place on this album. It’s great to have Clark Terry on the album, but his comic “mumbles” singing (which came from his experience with the “Tonight Show” band, not Ellington) only detracts from the beauty of “Fluerette Africaine”. Similarly, Lizz Wright‘s wordless vocals on “Backward Country Boy Blues”, Nir Felder‘s sitar-like guitar on Carrington’s original “Grass Roots” and Shea Rose‘s pseudo-sexy reading of the Ellington poem “Music” on “REM Blues” do nothing to enhance the music. And when Tia Fuller, Antonio Hart, and Robin Eubanks join in on a collective improvisation during the trio’s version of “Switch Blade”, the horns just get in the way of a fascinating trio exploration. When the trio plays alone, as on “Wig Wise” and “Very Special”, the album succeeds in getting the feel of the original album, even though Carrington’s trio creates intensity in an entirely different way than Ellington, Mingus and Roach. When it veers away with over-produced sounds, funk grooves and political soundbites, the timelessness of the original music is lost. Carrington’s previous album, “The Mosaic Project” was a triumphant celebration of women jazz musicians; “Money Jungle” certainly deserves the same praise, but perhaps it’s best to leave the original alone.