Phil Woods once quipped that “1968 was not exactly a swinging year in history”. The same could be said for every year between 1963, when John F. Kennedy was assassinated, and 1974, when Richard Nixon resigned the US presidency. During this period, there was a great cultural divide between the generations and between the political parties. Young liberals found plenty of issues to protest: the Vietnam War, civil rights, the Cold War, foreign dictatorships, human rights, and the environment. Older conservatives tried to ignore or dismiss the younger generation, but it became clear that the world was going to change, with or without the older generation’s blessing. When the Beatles came to America, rock music engulfed a diverse music scene, and there was no guarantee that any other type of music would survive. Rock music reflected the events of its time, and virtually every other form of popular art (film, music, television, books) felt the pressure to either be current or be forgotten. Faced with steadily declining audiences, jazz was also fighting for its very existence. So in retrospect, it’s not too hard to see why protest jazz, which had only played a minor role in past eras, became prominent in this turbulent era.

Phil Woods once quipped that “1968 was not exactly a swinging year in history”. The same could be said for every year between 1963, when John F. Kennedy was assassinated, and 1974, when Richard Nixon resigned the US presidency. During this period, there was a great cultural divide between the generations and between the political parties. Young liberals found plenty of issues to protest: the Vietnam War, civil rights, the Cold War, foreign dictatorships, human rights, and the environment. Older conservatives tried to ignore or dismiss the younger generation, but it became clear that the world was going to change, with or without the older generation’s blessing. When the Beatles came to America, rock music engulfed a diverse music scene, and there was no guarantee that any other type of music would survive. Rock music reflected the events of its time, and virtually every other form of popular art (film, music, television, books) felt the pressure to either be current or be forgotten. Faced with steadily declining audiences, jazz was also fighting for its very existence. So in retrospect, it’s not too hard to see why protest jazz, which had only played a minor role in past eras, became prominent in this turbulent era.

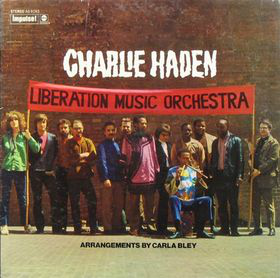

Still, the mixture of jazz and politics was risky and explosive. In the late 1960s, bassist Charlie Haden wrote “Song for Ché” as a response to the politically-motivated assassination of Argentinian revolutionary Ché Guevara. In 1971, Haden performed the piece in Portugal with Ornette Coleman, and he dedicated his performance to the Black People Liberation Movement in Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau and Angola. The combination of the hot-button issue and Haden’s passionate performance elicited continuous cheers from the audience, but Portugal’s Fascist government was not similarly moved. Haden was jailed and questioned by government officials before being rescued by an American cultural attaché. While the first recording of “Song for Ché” was a live version with Coleman, it is best known from its appearance on Haden’s 1969 album, “Liberation Music Orchestra”.

The Liberation Music Orchestra was a medium-sized ensemble featuring some of the greatest innovators in progressive jazz: Don Cherry and Michael Mantler (trumpets); Roswell Rudd (trombone); Bob Northern (French horn); Howard Johnson (tuba); Perry Robinson, Gato Barbieri and Dewey Redman (reeds); Carla Bley (piano); Sam Brown (guitar); Haden (bass); Paul Motian (drums), and Andrew Cyrille (percussion). Haden had considered forming the LMO several years earlier, when he first heard the songs of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1937). The songs reflected the stories of the international forces (including the 3000 American members of the “Abraham Lincoln Brigade”) which fought to maintain Spain’s democratically elected government against the Facist regime of Francisco Franco. Haden found correlations between the long-concluded war in Spain and the then-current war in Vietnam, and while the album has only one direct reference to Vietnam, it’s clear that the anger and passion of the performances are linked to the escalating and seemingly futile battles in Indochina.

Most of the arrangements for the album were created by Carla Bley, whose unique gifts were just beginning to be recognized. She had enjoyed recent acclaim for her scores on Gary Burton’s album, “A Genuine Tong Funeral”, and at the time of the LMO recordings, she was working on her opera “Escalator over the Hill”. Both “Tong” and “Escalator” are important companion pieces to “Liberation Music Orchestra”: not only did they feature many of the same musicians as the LMO, they also displayed Bley’s ability to combine diverse musical genres. “Liberation Music Orchestra” is not as wide-ranging as the other albums, but it has been rightly called “proto-world music”. Bley’s scores move effortlessly between the seemingly disparate worlds of Spanish folk music and progressive jazz, and the album also includes nods to the Berlin cabaret music of Kurt Weill and the polytonal/polyrhythmic concepts of Charles Ives.

What is immediately apparent from the opening tracks is that the group has a rougher ensemble feel than other groups of its size (vibrato and intonation are given great latitude throughout the album). Yet, it is clear that the LMO is in complete control of this music, as evidenced by the perfectly executed diminuendo on “Song of the United Front” and the stunning music that leads up to Cherry’s explosive cornet solo on “El Quinto Regimente”. On the latter, the LMO’s characterization of an amateur Spanish band builds with great intensity, so that Cherry’s solo entrance seems to be a natural outgrowth of what came before. As Cherry begins to improvise, the rhythm section of Bley, Haden and Motian quickly adds to the turbulence, while members of the band double on percussion. When the horns come back for a brief reprise of the theme under Cherry, they seem less organized and more disillusioned. Gradually, some of the other horns join into the improvisation. Brown plays a percussive flamenco-styled solo accompanied by handclaps from the band and occasional moans from Rudd’s trombone. Haden’s intense solo starts with great backing from Motian’s cymbals and (later) from Northern’s French horn.

The band then segues into a Rudd feature, “Los Cuatros Generales”. Near the end of Rudd’s intense solo, Haden dubs in a field recording of the original folk song. These overdubs are the most controversial aspects of the album. While it seems that they were included to bring together the new and traditional interpretations of the music, they sound like distractions instead of embellishments (Years later, Haden refined the technique with his Quartet West albums, where he interpolated classic jazz recordings within his group’s retro-styled arrangements. In those instances, he did not have the archival recordings and the live musicians playing simultaneously.) The suite of Spanish songs concludes with “Viva La Quince Brigade”, a showcase for Barbieri’s searing tenor sax. Starting the piece like a contemplative ballad, Barbieri is soon shrieking at the top of his horn. The band enters with the melody while Barbieri’s fierce solo continues, and to make things even more chaotic, another overdub is thrown into the mix. In an intriguing segue, the band re-enters with an arranged passage in a different tempo while Barbieri’s solo winds down. Bley prefaces and concludes the suite with her cheekily titled originals, “The Introduction” and “The Ending to the First Side”. These pieces, which are actually variations on the same material, are effective bookends for the first half of the album.

“Song for Ché” opens with Haden playing his plaintive melody unaccompanied. On the second chorus, the rhythm section and horns enter gradually, but when Haden starts to improvise, his primary accompaniment is from bells and cymbals. Near the end of his solo, Haden strums his bass to evoke a flamenco guitar. The engineer pans Haden towards the left channel, and a recording of Cuban singer Carlos Puebla performing his Ché Guevara tribute, “Hasta Siempre”, is dubbed in alongside Haden’s solo. While the historical connection is valid, the insertion of the recording is particularly jarring as it plays in a different key than Haden! Cherry solos next on a pair of bamboo flutes (also not in tune with each other), and then Redman takes over for an impassioned tenor solo. While Redman includes plenty of shrieks, he tends to stay within the normal range of the tenor rather than going for the stratosphere like Barbieri. Redman leads the way into the ensemble’s loose but passionate restatement of the theme.

Ornette Coleman’s “War Orphans” features a remarkable arrangement by Bley. On the surface, it seems that the horns don’t have much to do—just a few sustained notes under Bley’s free piano solo and the lively interaction of the rhythm section. Yet, Bley subtly increases the horn’s participation bit by bit, so that by the end of the arrangement, they threaten to completely engulf the rest of the group. As soloist, Bley carries a great responsibility to maintain interest throughout the work, and to build the improvisation at the same pace as the horns. On later LMO arrangements—including the stunning “Throughout” from “Not in Our Name”—she entrusts other soloists to take that role. Bley’s “The Interlude (Drinking Music)” offers a brief respite from the intensity before the album’s final political statement, “Circus ’68 ‘69”. The latter piece, composed and arranged by Haden, attempts to recreate a scene from the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention, where the New York and California delegates sang “We Shall Overcome” after the defeat of a resolution on Vietnam. The rostrum tried to drown out the protest song by having the convention orchestra play “Happy Days Are Here Again” and “You’re A Grand Old Flag”. Haden splits the LMO into two antiphonal sections, but the quotes are lost in the general melee of simultaneous free improvisations. At the conclusion of “Circus”, Rudd leads the band in a straight-forward rendition of “Overcome” to close out the album.

Although their album received critical praise and international awards, for several years it appeared that the Liberation Music Orchestra was a one-off ensemble. But in 1982, Haden—newly incensed by Ronald Reagan’s policies in Latin America—convened a new version of the LMO for the album “Ballad of the Fallen”. There were three more songs from the Spanish Civil War, plus songs from Chile and El Salvador. Haden seemed to settle an old score by recording “Grandola Vila Morena”, a song that was played on Portuguese radio in 1974 as a signal to young rebels to begin their revolt against the fascist government. From this point on, Haden would reassemble the LMO for concert appearances, but each time they recorded in the studio, there was fresh repertoire and new personnel. The 1990 CD “Dream Keeper” takes on apartheid with performances of the African National Congress anthem “Nkosi Sikelel’i Afrika” and Haden’s ebullient original “Spiritual”, while the title suite alternates Bley’s original themes with music from Venezuela, El Salvador and Spain. On both “Spiritual” and “Dream Keeper”, the LMO is augmented by the Oakland Youth Chorus. The final LMO album was 2004’s “Not in Our Name”, which protested the US-led war in Iraq. All of the music was by American composers, but as Bley stated in a pre-concert television interview, the music was emphatically not patriotic. That same television show featured highlights from the LMO’s performance at Marciac, France; Haden started the concert by telling the audience, We are on a campaign to send George W. Bush and Dick Cheney to Devil’s Island!

Ten years later, Bush and Cheney are still free men, but that does not diminish the efforts of Haden and the LMO. Changes have occurred, and even if the LMO wasn’t directly responsible, Haden and his fellow musicians did their part in raising awareness of issues that troubled the world. In 1972, in the midst of that decade of political turmoil, Leonard Bernstein eloquently stated, Art never stopped a war and never got anybody a job. That was never its function. Art cannot change events. But it can change people. It can affect people so that they are changed…because people are changed by art—enriched, ennobled, encouraged—they then act in a way that may affect the course of events…by the way they vote, the way they behave, the way they think. And while Haden has now transitioned from this world, there are still plenty of issues left to raise. In Carla Bley’s moving obituary to Haden, she said that she and Haden were thinking about creating a new LMO album concerning the environment. Bley and the LMO alumni should make the album anyway. While the rich tone of Haden’s bass would be absent, his spirit would envelope every note. Could there be a more fitting tribute to this jazz master?