Sometime in the 1950s, Frank Sinatra and Jeri Southern were performing at the same theater. When Sinatra was informed that Southern was leaving the building, he rushed down the backstage hallways wearing nothing but a bathrobe, and when he found Southern, he gave her such a strong bear hug that he nearly hurt her. He professed his long admiration of her music and encouraged her to continue her work. A minimalist long before the term was popular, Southern’s style was so understated that casual listeners assumed she wasn’t making any changes to the songs she performed. Yet, those who listened closely discovered her subtle swing, intimate delivery and intense dedication to lyrics. The clip below shows Southern performing Ray Noble’s “I Hadn’t Anyone Till You”. Her stage presence may seem passive but listen to the changes she makes to the melody, especially in the second chorus.

Jeri Southern was an intensely private person. The sudden rise to fame which came in the wake of her hit records “You Better Go Now” and “When I Fall In Love” must have come as a shock to the 25-year-old native of Royal, Nebraska. The success of these introspective sides, in 1951 and 1952 respectively, was a pleasant surprise in an era more famous for pop hits like “Come On-A My House”, “Mule Train” an d “Doggie in the Window”. Southern had studied classical piano and voice while still in Nebraska, but when she heard a jazz combo in an Omaha hotel bar, she decided to move to Chicago to become a nightclub pianist. While there, the former Genevieve Lillian Hering became Jeri Southern—apparently inspired by a bottle of Southern Comfort consumed one night with her new manager, Dick LaPalm, and inadvertently setting off a string of album titles which punned on her name. She was goaded into singing by a club owner (the same has been said of Nat King Cole, but both stories may be true), and her following included then-DJ Dave Garroway and fellow singers Anita O’Day and Peggy Lee. She also began an eight-year association with Decca Records, which would become her longest label affiliation.

d “Doggie in the Window”. Southern had studied classical piano and voice while still in Nebraska, but when she heard a jazz combo in an Omaha hotel bar, she decided to move to Chicago to become a nightclub pianist. While there, the former Genevieve Lillian Hering became Jeri Southern—apparently inspired by a bottle of Southern Comfort consumed one night with her new manager, Dick LaPalm, and inadvertently setting off a string of album titles which punned on her name. She was goaded into singing by a club owner (the same has been said of Nat King Cole, but both stories may be true), and her following included then-DJ Dave Garroway and fellow singers Anita O’Day and Peggy Lee. She also began an eight-year association with Decca Records, which would become her longest label affiliation.

Southern’s first recordings in 1949 and 1950 were only distributed on the London label, and were not very representative of her later style. By the time of “You Better Go Now”, she had codified her approach with her soft intimate vocals—based closely on her speaking voice—with support from her piano and a studio orchestra. In the notes to a reissue of Southern’s Decca sides, Gene Lees praised this track for its “simplicity [and] the exquisite lack of affectation or mannerism.” Much has been made about Southern’s understated style, but her vocal art was much more complex than that. She was a master of dynamics, and she effectively used them to emphasize the lyrics. On her 1958 collaboration with guitarist Johnny Smith, she brings the title line of “Have You Forgotten So Soon” down to nearly a whisper to remind her lover of his broken promises. And during an 8-bar interlude in “Something I Dreamed Last Night”, she makes lightning fast changes from pianissimo to fortissimo as the lyrics describe a dream breaking into reality.

Southern had hits with well-written songs, and her later albums were marked by an extraordinary repertoire of obscure and standard material. The  fact that Southern’s initial successes had been ballads was not lost on Decca, and most of her recordings for the label focused on slow to medium tempo arrangements. Several of the albums featured large studio orchestras and overwrought settings, but on the 1954 album, “Warm Intimate Songs in the Southern Style” (later reissued as “Southern Hospitality”), Southern performs with just a trio featuring guitarist Dave Barbour. On selections like “The Very Thought of You”, “You’re Nearer”, “It Never Entered My Mind” and Tennessee Williams’ “Cabin”, she offers a unique instrumental style featuring free rubato vocals over atmospheric piano and guitar chords and bowed string bass. It’s not a jazz album in any sense of the term, but Southern’s renditions of these songs built her reputation as a nonpareil interpreter of American popular music.

fact that Southern’s initial successes had been ballads was not lost on Decca, and most of her recordings for the label focused on slow to medium tempo arrangements. Several of the albums featured large studio orchestras and overwrought settings, but on the 1954 album, “Warm Intimate Songs in the Southern Style” (later reissued as “Southern Hospitality”), Southern performs with just a trio featuring guitarist Dave Barbour. On selections like “The Very Thought of You”, “You’re Nearer”, “It Never Entered My Mind” and Tennessee Williams’ “Cabin”, she offers a unique instrumental style featuring free rubato vocals over atmospheric piano and guitar chords and bowed string bass. It’s not a jazz album in any sense of the term, but Southern’s renditions of these songs built her reputation as a nonpareil interpreter of American popular music.

Southern had opportunities to sing up-tempo songs throughout her career, and on these tracks, her vocals had an effortless swing. However, she seemed unable to transmit that rhythmic lilt through her fingers. Her attempts to swing on piano are rather awkward, and her solos on the 1955 trio album “Southern Style” and its follow-up, “Jeri Gently Jumps” are flat-footed and uninspired. Yet somehow, Southern could maintain this unusual rhythmic dichotomy between her voice and her piano, and neither one seemed to affect the other! Of course, when the tempos came down for the ballads, Southern could easily revert to her very effective rubato style. In fact, two of the better tracks on “Southern Style” were ballads composed by Southern and her then-husband Ray Hutchinson. “I Don’t Know Where To Turn” is a stark representation of loneliness set in a standard 32-bar AABA form, but the stunner is “My Letters”, a song with several unexpected modulations and a form that seems to defy standard analysis. “Jeri Gently Jumps” featured a small band led by Ralph Burns. It is a jazzier date, and the fine performers on trumpet, trombone and accordion (none of whom have ever been identified) share the solos with Southern. This album showed that Southern was indeed capable of performing lighter material without sacrificing her unique style. The well-programmed track list contrasted sparkling versions of “No Moon At All”, “Everything but You” and “I’ve Got Five Dollars” with moody renditions of “My Old Flame”, “My Ideal” and a sensual take on “Romance in the Dark”.

Southern was a fan of Mel Tormé, and when she heard his initial album with the Marty Paich Dek-tette, she contacted Paich to see if she could record with the group. Paich had initially formed the 10-piece band as a one-off affair for Tormé’s album, but he reform ed the group for additional albums with Tormé and other musicians. Southern was the first vocalist after Tormé to record with the Dek-tette. The resulting album “Southern Breeze” was both her debut album for Roulette, and one of her finest recordings. The Dek-tette’s instrumentation was an adaptation of the Miles Davis Nonet and the Gerry Mulligan Tentette. Its sound reflected the cool jazz style popular in California during the mid-50s, and Paich’s arrangements yielded an easy relaxed swing. This style fit right in with Southern’s vocals and she sounds very comfortable in this environment (even the album cover shows her in a relaxed pose!). The album features some of the most humorous songs in Southern’s discography, including the sardonic “Down with Love” (by Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg) and the folksy—to extreme—“Lazy Bones” (by Hoagy Carmichael and Johnny Mercer). On the former, she sings the song straight with only a slight touch of humor to her delivery (as usual, letting the song speak for itself), and on the latter, she is paired with the tuba of John Kitzmiller. Paich’s charts are a delight throughout and on “He Reminds Me of You”, he echoes the lyric about a new lover who shares traits with the old beau by quoting “Godchild” from the Davis Nonet’s repertoire. Southern’s other Roulette albums are also exceptional: the aforementioned album with Johnny Smith is a fine collection of ballads that highlights the musical sensitivity of both leaders. “Coffee, Cigarettes and Memories” features a full orchestra conducted by Lennie Hayton, and includes definitive versions of “Spring Will Be A Little Late This Year”, “Detour Ahead” and “Yesterdays”. The title track also includes the only known instance of Southern overdubbing her voice, providing a dialogue between the main and counter melodies.

ed the group for additional albums with Tormé and other musicians. Southern was the first vocalist after Tormé to record with the Dek-tette. The resulting album “Southern Breeze” was both her debut album for Roulette, and one of her finest recordings. The Dek-tette’s instrumentation was an adaptation of the Miles Davis Nonet and the Gerry Mulligan Tentette. Its sound reflected the cool jazz style popular in California during the mid-50s, and Paich’s arrangements yielded an easy relaxed swing. This style fit right in with Southern’s vocals and she sounds very comfortable in this environment (even the album cover shows her in a relaxed pose!). The album features some of the most humorous songs in Southern’s discography, including the sardonic “Down with Love” (by Harold Arlen and E.Y. Harburg) and the folksy—to extreme—“Lazy Bones” (by Hoagy Carmichael and Johnny Mercer). On the former, she sings the song straight with only a slight touch of humor to her delivery (as usual, letting the song speak for itself), and on the latter, she is paired with the tuba of John Kitzmiller. Paich’s charts are a delight throughout and on “He Reminds Me of You”, he echoes the lyric about a new lover who shares traits with the old beau by quoting “Godchild” from the Davis Nonet’s repertoire. Southern’s other Roulette albums are also exceptional: the aforementioned album with Johnny Smith is a fine collection of ballads that highlights the musical sensitivity of both leaders. “Coffee, Cigarettes and Memories” features a full orchestra conducted by Lennie Hayton, and includes definitive versions of “Spring Will Be A Little Late This Year”, “Detour Ahead” and “Yesterdays”. The title track also includes the only known instance of Southern overdubbing her voice, providing a dialogue between the main and counter melodies.

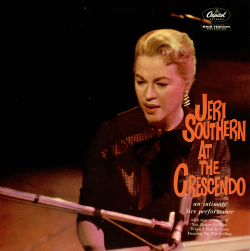

In 1959, Southern moved to Capitol Records where she recorded her final two albums. The first was a collection of Cole Porter songs, on which Southern was accompanied by a studio orchestra arranged and conducted by Billy May. May’s fast, brassy arrangements might seem to be an odd match for Southern’s reserved style, but the pairing works quite well. In the liner notes, Southern praised May’s originality: “I don’t know how he comes up with these ideas”, citing his Mozartean take on “Which?” and his roaring 20s version of “Don’t Look at Me That Way”. Southern adapts her style to May’s throughout, but their best artistic compromise may be on “It’s All Right with Me” where Southern sings the melody in long meter alongside May’s commentaries in double time. The second album was recorded live at the Crescendo in Hollywood. Southern had a long history of  severe performance anxiety, so recording this album must have been a nerve-racking experience for her. Although the cover depicts her singing and playing piano, she only plays on four of the album’s ten tracks, where she is accompanied only by Kitzmiller’s string bass. For the rest of the album, she is backed by a rhythm section (with Dick Hazard on piano) and Edgar Lustgarden’s rich cello. The live setting gave Capitol an excuse to record new stereo versions of Southern’s Decca hits. Close listening reveals the appreciation in Southern’s voice as the audience recognizes “Dancing on the Ceiling”, “When I Fall In Love” and “You Better Go Now”. The album also includes “I’m Just a Woman”, a song by Gail Allen who would later write songs with Southern. The lyrics might offend modern-day feminists, but Southern always enjoyed singing bluesy numbers and she obviously felt quite comfortable with this one.

severe performance anxiety, so recording this album must have been a nerve-racking experience for her. Although the cover depicts her singing and playing piano, she only plays on four of the album’s ten tracks, where she is accompanied only by Kitzmiller’s string bass. For the rest of the album, she is backed by a rhythm section (with Dick Hazard on piano) and Edgar Lustgarden’s rich cello. The live setting gave Capitol an excuse to record new stereo versions of Southern’s Decca hits. Close listening reveals the appreciation in Southern’s voice as the audience recognizes “Dancing on the Ceiling”, “When I Fall In Love” and “You Better Go Now”. The album also includes “I’m Just a Woman”, a song by Gail Allen who would later write songs with Southern. The lyrics might offend modern-day feminists, but Southern always enjoyed singing bluesy numbers and she obviously felt quite comfortable with this one.

And then it was all over. Sometime within the next few years, Southern withdrew from all public performances and recordings. The reasons why she retired are enveloped in mystery, and the accounts from the interviewees for this article seemed to disagree on every point. Except for a 1962 promotional radio show for the US Navy, Southern made no more recordings as a vocalist, and did not record any piano tracks until shortly before her death in 1991. She disliked the music business, and she had been forced to record several inferior songs for single releases (although to be fair, she also recorded good songs like “An Occasional Man” and “Fire Down Below” for the 45rpm market). Ralph J. Gleason’s liner notes for the Crescendo album states that Southern rarely traveled to clubs in cities other than LA, Chicago and San Francisco. One friend claims that Southern’s voice was failing her, and another said that her stage fright fueled her increasing dependency on alcohol. Eventually, Southern stopped drinking, and she dedicated her retirement years to composing, teaching and raising her child. One of her collaborations with Allen, “Touch the Earth” was recorded by Tony Bennett and Peggy Lee, and Southern briefly delved into film composition with her partner Hugo Friedhofer. She wrote a textbook “Interpreting Popular Music at the Keyboard”, and in her final years, she was a mentor to vocalist David Silverman. At her death—one day before her 65th birthday—she was planning to record a new album of songs by Arthur Schwartz. Southern’s daughter, Kathryn King, said that the arrangements for that album were to be classically-inspired fantasies based on the original songs. Silverman continues to promote the legacy of Jeri Southern with his recordings of her original compositions.

Jeri Southern still holds a strong fan base in Britain and Japan, and many of her recordings are available on CDs from those countries. The best domestic single-disc compilation of her work is “The Very Thought of You”, a collection of Decca tracks compiled and produced by King and Orrin Keepnews. Jasmine’s “The Dream’s on Jeri” includes several fine radio, TV and live recordings. There is still no comprehensive collection of her singles, and her albums may become harder to find with changing copyright laws in England. Still, her work is worth seeking out. If the Sinatra story reveals anything, it is that Jeri Southern possessed a talent that inspired awe from fans high and low, far and wide.