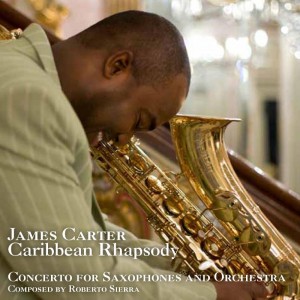

Saxophonist James Carter has been part of the New York jazz scene for over 20 years. His imaginative, risk-taking style has brought both fans and detractors, but the energetic spirit of his playing has brought some of those detractors over to his side. Carter discusses that and tells about the creation and recording of a new saxophone concerto with Jazz History Online’s Marissa Dodge.

Marissa Dodge: Considering that Caribbean Rhapsody is both a departure from your other recordings and a new composition, what was your approach to this project?

James Carter: I think the process was easier because I was there since the inception of the piece, and I had some say every step of the way on what was going to be written and on what was going to be executed. So that took a whole lot of pain out of it, as opposed to a previous situation that happened in 2000 where a Dutch composer came to me and already had the composition written out with me in mind, but I didn’t have any musical or intellectual input prior to rehearsal. I wasn’t able to deal with that at that particular time anyway because I was dealing with two albums simultaneously; “Layin’ in the Cut,” and “Chasin’ the Gypsy.” When Roberto Sierra pitched the concerto to me, he said, “I’ve been listening to a good portion of your discography to date, and I’d like to write a concerto for you.” My heart immediately sank, and I was thinking about my experience with the Dutch composer. But Roberto said that we’d get together and discuss certain excerpts and things like that. So I had some involvement in what the final ink was going to be, so that took some of the angst out of it. At the same time it also fueled me to a point where I had some liberties. The main thing at the world premiere was making sure that the time factor was as tight as possible, as far as reading the music and the improv sections. The written sections were pretty much a synergy—one and the same, and as a result, we were able to get through it. As time progressed, I was able to relax on certain things and I was able to hear different nuances, to hear the tenor and the soprano with more of a human quality as opposed to, “OK, this section is assigned to tenor, this piece is assigned to soprano,” it’s more like, “This is the male and this is the female role now,” and as a result, this opened up a lot more possibilities.

had the composition written out with me in mind, but I didn’t have any musical or intellectual input prior to rehearsal. I wasn’t able to deal with that at that particular time anyway because I was dealing with two albums simultaneously; “Layin’ in the Cut,” and “Chasin’ the Gypsy.” When Roberto Sierra pitched the concerto to me, he said, “I’ve been listening to a good portion of your discography to date, and I’d like to write a concerto for you.” My heart immediately sank, and I was thinking about my experience with the Dutch composer. But Roberto said that we’d get together and discuss certain excerpts and things like that. So I had some involvement in what the final ink was going to be, so that took some of the angst out of it. At the same time it also fueled me to a point where I had some liberties. The main thing at the world premiere was making sure that the time factor was as tight as possible, as far as reading the music and the improv sections. The written sections were pretty much a synergy—one and the same, and as a result, we were able to get through it. As time progressed, I was able to relax on certain things and I was able to hear different nuances, to hear the tenor and the soprano with more of a human quality as opposed to, “OK, this section is assigned to tenor, this piece is assigned to soprano,” it’s more like, “This is the male and this is the female role now,” and as a result, this opened up a lot more possibilities.

MD: Were there certain compositions, in any genre, that you drew inspiration from as you contemplated recording this concerto? Or was there anything you compared it to stylistically?

JC: No. Like I said earlier, it was literally a babe in and of itself. We were there during the conception, the finessing, and all that other good stuff all the way up to the world premiere in 2002.

MD: Can you share some insight into how you achieve your balance of technical execution and emotional expressiveness, and how you blend the two so seamlessly?

JC: The main thing is that if you have ideas of how you’re supposed to sound and execute on any given instrument, it’s the ability to have that thought in mind. To be able to put it in my head and say, “I want to do this and I need the technical facility to be able to do this particular thing,” but don’t get involved to the point where it winds up being a crutch, so to speak. It’s more or less a facilitator, the technical ends aren’t the ends in and of itself.

MD: What are the internal differences between classical and jazz for you? Are you using different skills or different parts of your mind for each?

JC: I knew there are a particular set of parameters that had to be used in order to play any particular genre, but I never said to myself, “I’m going to play like Sigurd Rascher or Frederick Hemke or Marcel Mule”. Once again, with the inception of this piece, the operative thing is that it was written with me in mind and the particular talents that I’m able I’m able to bestow. The same thing goes with cats who write certain pieces for Ornette Coleman. There was a piece that he was supposed to play but Ornette was having health troubles and couldn’t play it at the time. The composer had Ornette in mind when he composed the piece. That was the same with Roberto Sierra when he wrote for me. He didn’t have Marcel Mule in mind with an assist by me to do that. As a result, it was a piece that I could say, I don’t have to separate myself or put on the “classical hat” in order to get through it. It was me superimposed with a symphony orchestra. And there was always the further coaxing of Roberto saying, “Man, let it hang out, let it fly, let it happen, just be you.”

MD: So there was a jazz spirit at the sessions?

JC: Not only that, but I think this also might also answer a question that you posed earlier about my influences and inspiration when I prepared for this concerto. I love vocalists and in the classical genre, I dig Caruso. He certainly influenced a good portion of what’s happening not only within the classical genre but within music as a whole.

MD: You do have a singer’s vibe on the recording, there’s an operatic dynamic about it.

JC: I don’t know if it was a conscious thing, but if you listen to Chu Berry—particularly his things from the mid to late 30s—he definitely had an operatic delivery in his approach to tenor. That’s one thing I definitely dug about him. Listen to his “Body and Soul” of 1938, it sounds like Caruso to me. But directly from a saxophone standpoint, Chu Berry embodied the Caruso influence, and I took that and kind of ran with that from there and just dealt with voices. As the piece became a bit more familiar to me and I was able to let go of certain constraints, I was able to concentrate on the gender preferences that I mentioned between tenor and soprano and actually imply them in the piece.

MD: When you’re playing in different styles are there specific musicians or pieces that you think of when you’re capturing each style?

JC: I believe that jazz or music basically is an art of the moment. There are several mitigating factors from one live performance or one recording to the next, so I can’t say that there’s a consistent stream of things that influence across the board. I can’t say that it’s the drummer or the mouthpiece I’m using or anything else that’s going to influence it. It’s whatever the vibe is at the time. I think if you keep yourself open, the choice and the applications and the executions are infinite.

MD: A musician’s development includes the process of imitating other musicians before they find their own style. Do you remember when you felt you’d found your true voice?

JC: You always have to pay a toll musically and give homage and all. But I think one of the ultimate compliments that I received early was, I was doing “Conversin’ With The Elders” and I met up with Harry “Sweets” Edison and Buddy Tate. These guys could say that they’ve have heard it all, and a lot of the older guard have always said that everybody sounds the same. Here’s two guys that were staples in the Basie band and they’re telling me, “I hear this, but at the same time I hear you coming through it, and that‘s what‘s really hip about it.” More recently, this happened at a jam session in Harlem. Lou Donaldson came over to me and said, “You got a sound, man, you got a sound.” Before that, I had heard that Lou had joked that if the club owners wanted to make their money on me, they would have to charge for them to get out. He went from that standpoint to, “You got a sound, man. I hear you.” So it was gratifying in that sense.

MD: What are the most important things you’ve learned about live performance and recording?

JC: The main thing is to stay open. You have to recognize when inspiration comes up, and you never know how it’ll manifest at that given time. By being open, there’s always a combination of factors that occur in a great performance. You also have to recognize somebody else’s contribution and make the best of it. You never get a second chance to make a first impression, particularly in music. So listening, and being in the moment, and being able to react honestly.

MD: What are you thinking about doing next?

JC: The Festival of San Juan last year inspired me to bring back my old gypsy ensemble. I still have yet to fully manifest my gospel roots. But the main thing is always continuing to ‘shed as much as possible so I can be open for those instant moments and make the most of them.

MD: Do you meet many young people coming up who are promising?

JC: I just met one yesterday. I think in a whole lot of situations it’s about the equipment that they have. Once they have a good instrument, a whole lot of things will be able to come out. You have to look at your equipment as another appendage and the moment that you do that, it instills a different care as to how you take care of it. It won’t be like finding an instrument for a particular situation, but one that mirrors a musical personality with a set up that helps that come through. All that’s essential.

James Carter demonstrates his musical versatility on his next CD, The James Carter Organ Trio at the Crossroads. JC and counterparts, Gerard Gibbs, and Leonard King Jr. blend a potent brew of blues-built, high groove tracks, and sensory ballads. The project features compositions by jazz and blues royalty including Duke Ellington, Jack McDuff, Julius Hemphill, Matthew Gee, Maybelle Smith, and Sarah McLawler.