One night in early 1976, alto saxophonist Richie Cole and vocalist Eddie Jefferson were both hired as subs for the same New York City gig. Despite a 30-year age difference, Cole and Jefferson found a deep musical chemistry. Cole had been a member of Buddy Rich’s big band in the late 1960s, but had only recorded one album since 1970. Jefferson was a pioneer of vocalese—the craft of adding lyrics to previously recorded instrumental jazz solos—but despite a long partnership with saxophonist James Moody and several albums, he was still an under appreciated jazz giant. All that changed when Cole and Jefferson teamed up. By the end of 1976, they had recorded three albums together and played several live dates. In the same year, Irv Klatka’s Inner City label reissued a rare 1961 Jefferson album called “The Jazz Singer” and Jefferson appeared on a nationally-broadcast television show in a vocalese summit featuring Jon Hendricks, Annie Ross and Leon Thomas.

One night in early 1976, alto saxophonist Richie Cole and vocalist Eddie Jefferson were both hired as subs for the same New York City gig. Despite a 30-year age difference, Cole and Jefferson found a deep musical chemistry. Cole had been a member of Buddy Rich’s big band in the late 1960s, but had only recorded one album since 1970. Jefferson was a pioneer of vocalese—the craft of adding lyrics to previously recorded instrumental jazz solos—but despite a long partnership with saxophonist James Moody and several albums, he was still an under appreciated jazz giant. All that changed when Cole and Jefferson teamed up. By the end of 1976, they had recorded three albums together and played several live dates. In the same year, Irv Klatka’s Inner City label reissued a rare 1961 Jefferson album called “The Jazz Singer” and Jefferson appeared on a nationally-broadcast television show in a vocalese summit featuring Jon Hendricks, Annie Ross and Leon Thomas.

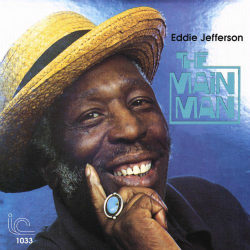

Klatka was probably anxious to record a new Jefferson album to follow up “The Jazz Singer”. However, it wasn’t until October 9, 1977 that Jefferson, Cole, Thomas (as producer) and musical director Slide Hampton gathered in the studio to create “The Main Man”, an album long considered Jefferson’s best, and a brilliant summation of his career to that point. The track list included several of Jefferson’s finest vocalese pieces, a delightful lyric transformation of a classic standard, a vocalese by one of Jefferson’s best followers, and several vehicles for Jefferson’s scat singing. Hampton assembled a diverse backup ensemble featuring obscure trumpeter Charles Sullivan (now known as Kamau Muata Adilifu), Horace Silver’s former tenor sax man Junior Cook, the World Saxophone Quartet’s baritone saxist Hamiet Bluiett, pianist Harold Mabern, bassist George Duvivier, drummer Billy Hart, conga players Harold White and Azzedin Weston, plus Hampton’s trombone and Cole’s alto. The players had a wide range of solo styles, but Hampton’s arrangements limited the instrumental solo space, and in an odd way, that helped unify the album’s sound.

Jefferson did not have a pretty voice, but his gravelly sound had an undeniable charm. His main vocal inspiration was Leo Watson, a member of the jazz novelty swing group the Spirits of Rhythm, whose solos were marked with outrageous humor and wild stream-of-conscious scat lines. Jefferson’s style wasn’t as zany as Watson’s, but he carried over many of Watson’s style elements into his own musical persona. The opening track of “The Main Man”, a swinging version of Duke Pearson’s “Jeannine” (with words by Oscar Brown, Jr.) features a passionate chorus by Cole and an energetic scat vamp by Jefferson. Jefferson’s scat is loaded with unusual intervals and accents, but he never loses the groove or the momentum. On “Night Train”, Jefferson’s lyric is a plaintive call to his lover and he uses subtle vocal inflections and small cries to emphasize the key words.

Next comes one of the masterpieces of the album, “Moody’s Mood for Love”. Although he did not receive credit on King Pleasure’s premiere recording, Jefferson wrote this touching lyric to a 1949 James Moody alto solo. This hipster’s love anthem became one of Jefferson’s signature pieces, and he recorded it several times during his career. On many recordings (by Jefferson, Pleasure and others), a female vocalist was brought in to sing the lyrics for the brief piano solo, but when a woman wasn’t available (as on “The Jazz Singer”), Jefferson would sing the solo in falsetto. I suspect that Klatka was unhappy with the earlier version and hired Janet Lawson, a respected vocalist from Chicago, to sing the piano solo on the remake. Lawson makes the most of her eight bars, and I think that her presence and rich voice inspired Jefferson to new depths of warmth. The fact that he is singing to someone seems to make his performance more romantic and touching. Klatka may have also had a say on the next track, “Body and Soul.” Jefferson had recorded a superb version of the Coleman Hawkins solo for “The Jazz Singer”, so on “The Main Man”, Jefferson sang his setting of Moody’s improvisation. Hampton’s arrangement puts the standard into a surging Latin-rock groove, with a highly effective transition into straight-ahead swing on the last bridge. The first side closes with a jam on Charlie Parker’s “Confirmation” with Jefferson contributing both original words and an extended scat solo. The lyrics salute Bird, and refer to bebop as “the savior of the nation”. Jefferson improvises a series of jagged lines with considerable accuracy, and keeps the mood light with unusual syllable choices.

I wouldn’t dream of giving away the joke on the second side’s opener, “Bennie’s From Heaven”, but suffice to say that the wife’s claim would now require DNA testing! Jefferson’s ingenious reworking of “Pennies From Heaven” has been covered by many artists (including Moody), but this original version is still the best, with Jefferson’s infectious good humor, a swinging arrangement by Hampton and a fine solo from Sullivan. On the next track, Jefferson sings his variation on Gershwin’s “Summertime”. Jefferson only adds a few words to the original lyrics but the mood is much more aggressive than other versions. Duvivier and Hart drive the band with force, and Jefferson delivers the lyrics as if he were cracking a whip. Jefferson had recorded Eddie Harris’ “Freedom Jazz Dance” with organist Mickey Tucker in 1974, but again the combination of Hampton’s arrangement, the outstanding horn soloists (Sullivan and Cook) and the dynamic rhythm section inspire Jefferson to a spirited and definitive performance. The album closes with an up-tempo version of “Exactly Like You.” It features Jefferson’s most conventional scat solo on the session, and judging from the fine communication between Sullivan and Jefferson, it’s too bad that they didn’t make another recording together.

Jefferson and Cole continued to work together for the next two years, and Jefferson also appeared as a guest artist on Dexter Gordon’s “Great Encounters” album. The Cole/Jefferson group was filmed at Chicago’s Jazz Showcase on May 6, 1979, and just two days later in Detroit, Jefferson was fatally shot after finishing the night’s gig. The gunman was acquitted, and no one else was ever charged in Jefferson’s murder. Later that year, the Manhattan Transfer—which had recorded with Cole and Jefferson just two weeks before Jefferson’s death—recorded a version of “Body and Soul” which featured Jefferson’s lyrics to the Hawkins solo. The second chorus was adapted to become a tribute to Jefferson. As part of the Transfer’s breakthrough “Extensions” album, it introduced many young listeners—including me—to Jefferson’s name and artistry. On their following album, “Mecca for Moderns”, the Transfer recorded “Confirmation” with Jefferson’s lyrics, along with two of his former collaborators, Jon Hendricks and Richie Cole. Hendricks, Cole and the Transfer are all still here today, a little mellowed with age, but they all continue to perform the music that Eddie Jefferson termed “the savior of the nation.”