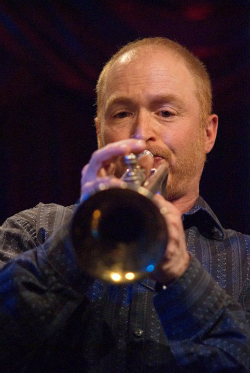

When Brad Goode first appeared on the Chicago jazz scene, his association with, and resemblance to the bebop legend Red Rodney led many fans and critics to believe that the young trumpeter would be the newest torchbearer for bebop. While Goode is fully conversant with all of jazz’s earlier genres, he’s never been one for stylistic preservation. Consequently, he has sought and developed his own unique approach to the music. For the past 20 years, he’s been working on a harmonic system that utilizes polytonality. It has not been met with universal acceptance; Goode says “When I started asking musicians to read these chords, they wanted me to go away and die”. Still, Goode has persevered, and his latest CD, “Chicago Red” (Origin 82634) offers some of his finest realizations of this controversial theory.

conversant with all of jazz’s earlier genres, he’s never been one for stylistic preservation. Consequently, he has sought and developed his own unique approach to the music. For the past 20 years, he’s been working on a harmonic system that utilizes polytonality. It has not been met with universal acceptance; Goode says “When I started asking musicians to read these chords, they wanted me to go away and die”. Still, Goode has persevered, and his latest CD, “Chicago Red” (Origin 82634) offers some of his finest realizations of this controversial theory.

Goode’s harmonic concepts can be a little daunting for the non-musician, so we’ll use the concept of language (shown in italics) to help explain. A person who can speak French and Spanish has a good start towards learning Portuguese. Yet, if that person does not know the unique words and sounds of the Portuguese language, he will have a hard time communicating with a Portuguese speaker. To be fully understood, he must learn the syntax and structure of Portuguese so that it feels natural. In musical terms, most jazz played today uses versions of the harmony developed with bebop. Chords were expanded with upper notes to give the improvisers greater flexibility in creating solos. Goode’s system is also designed to expand note choices, but instead of building a chord on a single root, Goode stacks two chords with different roots on top of each other. This means that the higher notes are different than in a bebop chord, and the typical methods used by soloists in maneuvering through bebop harmony will not work with Goode’s system. (In other words, French and Spanish bear similarities to Portuguese, but they are not the same as Portuguese). The chords Goode stacks on the existing harmony are not arbitrary; both the original and overlaid harmonies resolve independently. An improviser can work within either harmonic structure, but optimally he should work between both structures to bring out the polytonal aspect of the music. (So mastering Goode’s harmonic system is like mastering Portuguese after you know French and Spanish). One of the greates t challenges to this music is creating valid artistic statements without letting the technique get into the way (which is akin to speaking in sentences and paragraphs instead of one word at a time).

t challenges to this music is creating valid artistic statements without letting the technique get into the way (which is akin to speaking in sentences and paragraphs instead of one word at a time).

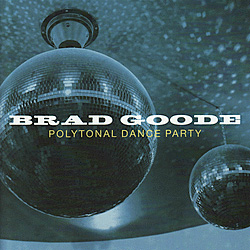

Goode has included polytonal compositions in several of his albums, but two of his recent CDs have focused on the concept. The first was “Polytonal Dance Party” (Origin 82519) recorded and released in 2008. In addition to Goode’s trumpet, the quintet featured pianist Jeff Jenkins, guitarist/sitarist Bill Kopper, bassist Ken Walker and drummer Anthony Lee. The album’s liner notes included an explanation of the polytonal technique by trumpeter/composer John McNeil, and reproductions of several of Goode’s lead sheets, including the expanded harmony. The music on the CD seemed to push the polytonal aspect at every turn, and at times, it seemed to revel in its own strangeness, with Goode playing the melodies of standards in different keys from the rest of the band. But the album also established the style of these performances, which are reminiscent of Miles Davis’ 1980s funk grooves (Goode’s open trumpet style is also indebted to Davis, but many of his wilder free-bop improvisations reveal inspirations from experimental players like Bill Dixon and Lester Bowie).

“Chicago Red” is much more successful overall. Part of its success is due to a restructure of the band’s personnel. Walker’s full and resonant acoustic bass is replaced by the light and flexible 5-string electric bass of Bijoux Barbosa, and Lee’s standard dr um set is replaced by that of Ghanian drummer Paa Kow. When I saw this band at Lannie’s Clocktower Cabaret in Denver, I was amazed at the tiny, shallow snare drum and small cymbals that Paa Kow used in his kit. He gets a high, crisp sound from these instruments, and the new combination of bass and drums gives an airy feeling to the rhythm section. Lebanese percussionist Rony Barrak adds welcome low frequencies and rhythmic diversion with his performances on the darbouka and the rik. Jenkins and Kopper seem to play less as accompanists on this album, which prevents the background from becoming dense and overwhelming. The word “polytonal” never appears in the liner notes, but most of the music clearly uses the technique. Goode’s solo on the opening track, “What Happens in Space City” has a great example of polytonal improvising as he skittles back and forth between two tonal centers. Barrak’s percussion and Koppel’s electric sitar add an exotic flavor to the polytonal remake of “St. Louis Blues”. In the solo section of that track, it is fascinating to hear the colliding harmonies of soloist Koppel and accompanist Jenkins. The polytonal technique is stretched to its furthest limits on “Mambo Disonante” where three different key centers are present at once! Jenkins’ ear-bending solo keeps the listener delightfully off-center, and after Goode’s relatively sedate solo, Barbosa’s fluid bass chorus feels like an abrupt change in tonality.

um set is replaced by that of Ghanian drummer Paa Kow. When I saw this band at Lannie’s Clocktower Cabaret in Denver, I was amazed at the tiny, shallow snare drum and small cymbals that Paa Kow used in his kit. He gets a high, crisp sound from these instruments, and the new combination of bass and drums gives an airy feeling to the rhythm section. Lebanese percussionist Rony Barrak adds welcome low frequencies and rhythmic diversion with his performances on the darbouka and the rik. Jenkins and Kopper seem to play less as accompanists on this album, which prevents the background from becoming dense and overwhelming. The word “polytonal” never appears in the liner notes, but most of the music clearly uses the technique. Goode’s solo on the opening track, “What Happens in Space City” has a great example of polytonal improvising as he skittles back and forth between two tonal centers. Barrak’s percussion and Koppel’s electric sitar add an exotic flavor to the polytonal remake of “St. Louis Blues”. In the solo section of that track, it is fascinating to hear the colliding harmonies of soloist Koppel and accompanist Jenkins. The polytonal technique is stretched to its furthest limits on “Mambo Disonante” where three different key centers are present at once! Jenkins’ ear-bending solo keeps the listener delightfully off-center, and after Goode’s relatively sedate solo, Barbosa’s fluid bass chorus feels like an abrupt change in tonality.

Many of the tracks on “Chicago Red” were recorded as untitled funk jams without melodies. About 16 different pieces were recorded (all first takes), and Goode picked the best ones for the album, adding titles after the fact. In a way, this method of recording offers the listener choices in appreciating the music. One could focus on the polytonal improvisations and the ways that Goode has expanded jazz’s harmonic language, or explore the album as a dramatic extension of the funk/fusion styles of Miles Davis. Either way, “Chicago Red” is an exciting adventure for fearless listeners.