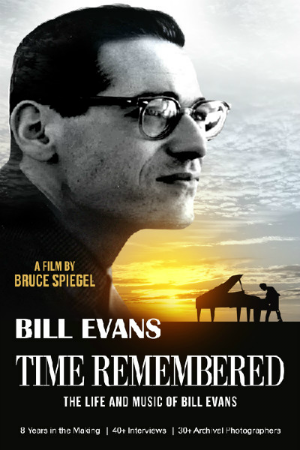

At the beginning of Bruce Spiegel’s documentary, “Time Remembered”, Chuck Israels says that he is constantly asked “What was Bill Evans really like?” Israels, who spent five years as Evans’ bassist, shakes his head and replies “Damned if I know”. While the ensuing 87 minutes of Spiegel’s film tells us a lot about Evans’ life and career, there are still many questions left unanswered. We may never know why Evans was so self-critical, how his music evolved, and—most importantly—why he became a heroin addict. However, as Israels notes, we can learn a lot about Evans through his music. While audio and video recordings may not yield answers to the questions posed above, they offer clues to the image that Evans wanted to present to his audiences.

At the beginning of Bruce Spiegel’s documentary, “Time Remembered”, Chuck Israels says that he is constantly asked “What was Bill Evans really like?” Israels, who spent five years as Evans’ bassist, shakes his head and replies “Damned if I know”. While the ensuing 87 minutes of Spiegel’s film tells us a lot about Evans’ life and career, there are still many questions left unanswered. We may never know why Evans was so self-critical, how his music evolved, and—most importantly—why he became a heroin addict. However, as Israels notes, we can learn a lot about Evans through his music. While audio and video recordings may not yield answers to the questions posed above, they offer clues to the image that Evans wanted to present to his audiences.

Evans was a very private person, but he told most of his life story to interviewers. Spiegel uses these audio interviews as a narrative thread for his film. Time and again, current interviews with Evans’ friends and colleagues begin with elaborations on Evans’ comments about important people or events in his life. We meet Debby Evans—the pianist’s niece and subject of his best-known composition, “Waltz for Debby”, early associates like bassist Connie Atkinson, famous collaborators such as Paul Motian, Jim Hall, Jack De Johnette, Marty Morell, Tony Bennett, Marc Johnson and Joe LaBarbera, and a plethora of famous pianists, including Billy Taylor, Eric Reed, Warren Bernhardt, and Bill Charlap. It took Spiegel eight years to make this film, and in the interim several of the interviewees have passed away. It’s a little eerie to see Motian, Hall, Taylor, Bob Brookmeyer and Don Friedman back from the dead, but it underscores the importance of Speigel making this film when he did.

The first half of the film traces Evans’ development from his childhood through his tenure with the Miles Davis Sextet. Throughout this section, we discover the strong bonds between Bill Evans and his older brother, Harry. Harry took great care of his brother, fending off bullies at school, offering love and guidance in place of their troubled parents, and being a presence in Bill’s problematic life (Harry’s widow relates that in 1963, Harry confronted Bill about his worsening drug habit and did his best to get Bill off heroin. Bill eventually returned the favor by paying Harry’s hospital bills near the end of his life). The film’s best segment discusses the making of Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue”, to which Evans played a crucial role. Speigel executes spectacular edits between Eric Reed’s contemporary performance of the opening lick from “So What” and the classic recording, and later in the same track, he jumps seamlessly between the LP and the “Robert Herridge Theatre” television performance (which was recorded between the two “Kind of Blue” studio sessions).

After an enlightening section on the Evans/LaFaro/Motian trio, the historical chronology begins to suffer. Spiegel follows the history of Evans’ ensuing trios all the way to 1970, then makes a sudden jump backward to talk about Evans’ personal life during the mid-sixties and his two duet albums with Jim Hall. Surprisingly, Evans’ Grammy-winning solo album “Conversations with Myself” and it’s two sequels are never discussed. The initial album elicited a great deal of controversy in its day because it was created through overdubbing. Those viewers who know the album will certainly recognize the triple track recording on the recurring “NYC’s No Lark”, but I suspect that few newcomers to Evans’ music will understand the significance of these recordings. The main film contains a brief mention of Helen Keane’s contributions as Evans’ longtime producer and manager. There is a short featurette on Keane included on the DVD and in the digital download, but this material truly belongs in the full documentary.

The film picks up the chronology in 1970, as Evans is busted on drug charges at a New York airport. As a plea deal, Evans joined a methadone program and finally kicked his heroin habit. What should have launched a new chapter in his life instead opened the final harrowing decade of Evans’ life. Evans’ outward appearance changed in the early 1970s, with facial hair, hip glasses and a new wardrobe. Then Evans decided that he wanted to be a father. His common-law wife, Ellaine, was unable to bear children, so Evans promptly dumped her for a younger woman. Ellaine responded by throwing herself in front of a subway train (as Gene Lees states elsewhere in the film, Evans hurt a lot of people in his lifetime). The new wife provided Evans with his own child and a loving stepchild, but by 1978, Evans starting shooting cocaine, and when his wife found the drug paraphernalia, the marriage fell apart. Soon after that, Harry was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and eventually committed suicide. Bill was devastated, and while he eventually rose to great artistic heights with his trio with Johnson and LaBarbera, he was hounded by suicidal thoughts of his own. By the time he died in September 1980, Evans was shooting up every 45 minutes.

“Time Remembered” offers a heartfelt tribute to Evans and his legacy. It is far from complete—important collaborations with composers George Russell, Gary McFarland, and Claus Ogerman are left out, as are seminal albums like “The Ivory Hunters”, “Know What I Mean?”, “Affinity”, “You Must Believe in Spring” and “We Will Meet Again”—but there is enough essential material to encourage viewers to further explore Evans’ legacy. We may never know all the ingredients in Bill Evans’ persona, but Bruce Spiegel’s film teaches us a lot about this remarkable musician.

At press time, “Time Remembered” is only available from Reel House as a digital download. A DVD release—delayed by problems with subtitles—has been promised in the coming months.