In the 1920s and 1930s, ensembles known as “territory bands” toured limited geographical areas from Kansas City through the southwestern United States. These big bands developed in relative isolation from the better-known groups from New York City and Chicago. Since only a few of these groups made recordings, most of what we know about the territory bands is anecdotal and highly subjective. However, the existing recordings show that the most progressive bands were centered in Kansas City, where the corrupt city government led by Tom Pendergast fostered an atmosphere where musicians could develop their art on the bandstand in heated jam sessions and within big bands. Here, Walter Page and pianist William—not yet Count—Basie collectively discovered a way to translate the rhythmic innovations of Louis Armstrong into the context of a big band. As a bassist, Page was probably the first to understand that his instrument was the heartbeat of the entire ensemble. For a band to swing as a group, the rhythm section had to set the example, and the long-standing team of Basie, Page, drummer Jo Jones (and eventually rhythm guitarist Freddie Green) rehearsed tirelessly to create a consistently swinging foundation for the band’s brass and reed sections. Page was originally a bandleader, but his group, the Blue Devils, was taken over by a local rival, Bennie Moten (right, with Basie and Moten conferring at the twin pianos). When Moten died after a botched operation, Basie took leadership of the group. The 1929-1932 recordings by Page’s Blue Devils and Moten’s orchestra show impressive progress in creating an ensemble conception of swing, but Basie’s group developed the concept further in the years between Moten’s demise in 1933 and the Basie band’s “discovery” by John Hammond in 1936.

Freddie Green) rehearsed tirelessly to create a consistently swinging foundation for the band’s brass and reed sections. Page was originally a bandleader, but his group, the Blue Devils, was taken over by a local rival, Bennie Moten (right, with Basie and Moten conferring at the twin pianos). When Moten died after a botched operation, Basie took leadership of the group. The 1929-1932 recordings by Page’s Blue Devils and Moten’s orchestra show impressive progress in creating an ensemble conception of swing, but Basie’s group developed the concept further in the years between Moten’s demise in 1933 and the Basie band’s “discovery” by John Hammond in 1936.

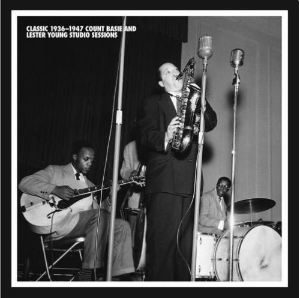

One night in Chicago, Hammond ditched out of a performance by the Benny Goodman band, and while spinning the dial of his car radio, he heard a broadcast by the then-unknown Basie band from the Reno Club in Kansas City. Hammond drove to KC to hear the band in person, and offered Basie the opportunity to bring his band to New York. Hammond intended to record Basie on Columbia, but Decca Records beat Hammond’s time with a hastily drawn exclusive recording contract. Hammond retaliated against Decca by bringing a quintet of Basie’s men into Columbia’s Chicago recording studio under the group name of “Jones/Smith, Inc.” The rhythm section of Basie, Page and Jones displayed a style that was unknown outside of Kansas City: a strong presence by the bass, with breezy high-hat cymbals and light piano chords, the latter informed by (and pared down from) stride piano. Together, the rhythm section made a cohesive ensemble sound that generated intense swing while sounding utterly relaxed. The two horn players, trumpeter Carl “Tatti” Smith and tenor saxophonist Lester Young, were members of Basie’s band, and both fairly new to recording. Smith recorded a half-dozen sides with the California Ramblers in 1931 (but nothing since), and the 27-year-old Young had never recorded before. Young’s style was basically formed by the time of this debut recording, and he exhibits remarkable confidence in his first solo, “Shoe Shine Boy”. Young’s style was called a direct opposite of Coleman Hawkins, but like most generalizations, the assertion is quite simplistic. True, Hawkins’ burly sound and harmonically based style was much different than Young’s light-toned and melodic approach, but both men realized that they could enhance an ensemble’s swing through the rhythmic force of their improvised lines. Young did it on “Shoe Shine Boy” by locking into the rhythm section’s enticing groove and punching out rhythm patterns that enriched the efforts of Basie, Page and Jones. The remarkable Jones/Smith, Inc. session  leads off Mosaic’s new box set “Classic 1936-1947 Count Basie and Lester Young Studio Sessions”, which also includes alternate takes for all four of the Jones/Smith sides, the Basie band’s Decca recordings, plus a plethora of Young’s small group masterpieces for Victor, Signature, Commodore, Keynote, Aladdin and Mercury. And as if 8 CDs of prime Basie and Lester weren’t enough, the National Jazz Museum in Harlem has just released the second volume of its “Savory Collection”, which features a full disc of live broadcasts by the Basie band recorded between 1938 and 1940, concurrent with their Decca and early Columbia sides.

leads off Mosaic’s new box set “Classic 1936-1947 Count Basie and Lester Young Studio Sessions”, which also includes alternate takes for all four of the Jones/Smith sides, the Basie band’s Decca recordings, plus a plethora of Young’s small group masterpieces for Victor, Signature, Commodore, Keynote, Aladdin and Mercury. And as if 8 CDs of prime Basie and Lester weren’t enough, the National Jazz Museum in Harlem has just released the second volume of its “Savory Collection”, which features a full disc of live broadcasts by the Basie band recorded between 1938 and 1940, concurrent with their Decca and early Columbia sides.

In order to compete with established New York bands, Basie had to expand his group from nine pieces to fourteen. Decca rushed the band into the studio as soon as the group settled into New York, and the discography for the first seven sessions (spanning just over a year from January 1937 to February 1938) reveals a constantly shifting personnel. Familiar names like Harry Edison, Bennie Morton, Dicky Wells, Earl Warren and Freddie Green gradually joined forces with the veterans Buck Clayton, Ed Lewis, Dan Minor, Herschel Evans, Young, Basie, Page and Jones. Not only did the band feature some of the finest soloists of its day, it was also a great study in contrasts. In the trumpet section, Lewis provided atmospheric growls (“Blues in the Dark”), Edison offered incisive statements (“Sent for You Yesterday”) and Clayton played with deep soul (“Good Morning Blues”). The trombone section featured Wells’ relaxed behind-the-beat phrasing (“Jive at Five”) juxtaposed against Morton’s rambunctiousness (“Out the Window”). Of course, the biggest contrast was between the band’s star tenor saxophonists, Evans and Young. Evans’ burly Hawkins-inspired style was the perfect balance to Young’s airy floating approach. The two rarely played back-to-back on the Decca sides, but each man received ample solo time so that comparisons were readily apparent. Evans’ greatest feature was the ballad “Blue and Sentimental”, but he plays essential roles on “Swingin’ at the Daisy Chain”, “Doggin’ Around” and “Georgianna”. Evans’ premature death in early 1939 prevented him from getting the accolades he deserved, but Mosaic’s annotator Loren Schoenberg takes great care to spotlight Evans’ important contributions. Young’s solos, in both their conception and execution, still amaze with their stunning originality. Tracks like “Every Tub”, “Texas Shuffle” and “Oh, Lady Be Good” are considered indispensable jazz classics, partially due to Young’s remarkable improvisations.

From the beginning, Basie produced amazing recordings for Decca. The first session included a spirited versions of “Honeysuckle Rose” and “Roseland Shuffle”, the latter featuring an inspired chase between Young and Basie. The next session produced “Boogie Woogie”, one of the greatest explorations of call-and-response patterns ever recorded. The piece was a head arrangement, which meant that the musicians developed and memorized their parts without written music. While heads were played by many bands of the era, the Basie band had perfected the genre further than anyone else. “Boogie Woogie” is loaded with call-and-response patterns from the basic (Jimmy Rushing ’s vocal parlay with band on the phrase “Yes, Yes”) through the complex (Rushing’s earlier choruses which have accompaniment by both a trumpet obbligato and a saxophone riff, all of which seems to answer each other) to the astounding (Basie’s four-bar introductions, which are all thematically related—not only in adjacent choruses but relating from one end of the record to the other!) The piece shows astonishing compositional unity, considering it was improvised on the spot! By July 1937, Basie brought in Eddie Durham, who effectively set the head arrangements into written form. At times, the seams between improvised and written sections were all too obvious (as on “Topsy”, where the A strain was clearly a head arrangement and the bridge was orchestrated), but Durham grew into the job quickly, writing brilliant settings like “Swingin’ the Blues”, “Sent For You Yesterday” and “Blue and Sentimental”. While written arrangements became a bigger part of the Basie repertoire in the coming years, Basie never abandoned the head arrangement, and even in the immediate post-Durham era, the band recorded (in Schoenberg’s felicitous phrase) endorphin-raising head arrangements like “Texas Shuffle”, “Panassie Stomp” and “Jumpin’ at the Woodside”. As Basie’s Decca contract came to a close, full band sessions alternated with small group sides. The 10 tracks of the rhythm section alone lack sufficient variety to maintain listener interest, but the sextet version of “You Can Depend on Me” and the reduced band arrangement of “Jive at Five” are among the highlights of not only Basie’s discography but of the swing era in general.

’s vocal parlay with band on the phrase “Yes, Yes”) through the complex (Rushing’s earlier choruses which have accompaniment by both a trumpet obbligato and a saxophone riff, all of which seems to answer each other) to the astounding (Basie’s four-bar introductions, which are all thematically related—not only in adjacent choruses but relating from one end of the record to the other!) The piece shows astonishing compositional unity, considering it was improvised on the spot! By July 1937, Basie brought in Eddie Durham, who effectively set the head arrangements into written form. At times, the seams between improvised and written sections were all too obvious (as on “Topsy”, where the A strain was clearly a head arrangement and the bridge was orchestrated), but Durham grew into the job quickly, writing brilliant settings like “Swingin’ the Blues”, “Sent For You Yesterday” and “Blue and Sentimental”. While written arrangements became a bigger part of the Basie repertoire in the coming years, Basie never abandoned the head arrangement, and even in the immediate post-Durham era, the band recorded (in Schoenberg’s felicitous phrase) endorphin-raising head arrangements like “Texas Shuffle”, “Panassie Stomp” and “Jumpin’ at the Woodside”. As Basie’s Decca contract came to a close, full band sessions alternated with small group sides. The 10 tracks of the rhythm section alone lack sufficient variety to maintain listener interest, but the sextet version of “You Can Depend on Me” and the reduced band arrangement of “Jive at Five” are among the highlights of not only Basie’s discography but of the swing era in general.

The concurrent release of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem’s set of Basie/Young airchecks allows easy comparisons between studio and live versions of the same music. The original recordings, made by legendary engineer Bill Savory, include 11 tracks recorded during Basie’s engagement at the Famous Door in New York, with additional performances recorded from Boston’s Southland Ballroom and Chicago’s Panther Room within the Hotel Sherman. As on the first volume of the Savory Collection, remastering engineer Doug Pomeroy has done wonders in rescuing and clarifying the original sound. Overall, the presence of the instruments is as good as on the studio recordings, and the airchecks convey the power and excitement the band could generate in person. Like the Decca recordings, the Savory album starts with “Honeysuckle Rose”, but the arrangement from the Famous Door is almost completely different from the Decca recording made 19 months earlier. A peppy version of “I Ain’t Got Nobody” features Young’s brief exchanges with the orchestra, a surprising contribution by Freddie Green and a burning vocal by Rushing. Evans, Clayton and Young play extended solos on a jam session version of “Rosetta”, and a newly discovered version of “Blue and Sentimental” includes a vocal chorus by Helen Humes (apparently someone thought this song could make the Hit Parade) and a different—and less effective—shout chorus near the end of the ar rangement. It’s rather disheartening to hear great improvisers like Young and Edison recreating their recorded solos on the live versions of “Every Tub”; Schoenberg writes that audiences of the time expected that, but such an argument hardly legitimizes the practice. Thankfully, on “Good Morning Blues”, we get a freshly created (and beautiful) Buck Clayton solo, plus an added Young clarinet obbligato behind Rushing’s vocal.

rangement. It’s rather disheartening to hear great improvisers like Young and Edison recreating their recorded solos on the live versions of “Every Tub”; Schoenberg writes that audiences of the time expected that, but such an argument hardly legitimizes the practice. Thankfully, on “Good Morning Blues”, we get a freshly created (and beautiful) Buck Clayton solo, plus an added Young clarinet obbligato behind Rushing’s vocal.

The suggested track sequence takes the recordings out of strict chronological sequence, but allows for back-to-back versions of the same arrangements. Among these comparative tracks are two versions of an officially-unrecorded chart on “Limehouse Blues”, and the album’s highlights, a pair of extended takes on “Texas Shuffle”. The first aircheck of “Shuffle” was made just 9 days after the Decca recording, and while the tempo is a little stodgy, the extended solos by Edison, Young (again on clarinet), Wells and Evans are quite good. About 7 weeks, they played it again at a brighter tempo, and everyone from the soloists to the ensemble players sounds more inspired (the sound is better too, with Jones’ bass drum kicks coming through with exceptional clarity). Moving to the later Savory recordings, the first version of “The Apple Jump” sounds like it was recorded in a large ballroom, and it’s great to hear the crowd reacting with whistles and cheers to this tremendously exciting band—Young said he loved to play for dancers, and I suspect he got a great kick out of this particular crowd. On a Chicago version of “Jumpin’ at the Woodside”, Young dutifully plays his recorded solo, and then soars over the band with a magnificent second chorus. Also from the Chicago airchecks is a fast and intense reading of “Roseland Shuffle” that tops the version made at the Famous Door nine months earlier. A great 1939 version of “Sent for You Yesterday” features another Young clarinet obbligato behind Rushing, and the entire trumpet section playing Harry Edison’s famous break from the Decca recording. “Swingin’ the Blues” from the same date, is a little rough around the edges but makes up in power and swing what it lacks in polish. The Boston airchecks from early 1940 show that the polish was indeed important. These tracks show the Basie band’s remarkable developments in just over 3 years, and point the way to the Basie orchestras of the 1950s through the 1980s. The album’s final track, which goes back two years to the May 1938 appearance at Randall’s Island, makes the point well: playing their theme song, “One O’Clock Jump”, the feeling is loose and relaxed but the ensemble playing has much less finesse than the later recordings. Of course, the swing was compelling in both editions of the band, and that was Basie’s primary objective.

With the conclusion of the Basie Decca recordings, Mosaic’s set focuses on Young’s small group recordings from 1941-1947 (The Basie/Young Columbia recordings were collected on a now-deleted Mosaic box; copies may still be available on ebay and other online outlets; otherwise, try a well-stocked library). Much has been written about Young’s sound and general mental state following his tenure in the Basie band. There is no doubt that in the 1940s, Young’s tone grew heavier and that his improvisations were more grounded, but it is a critical fallacy to pinpoint any particular event (even something as traumatic as his Army court-martial) to a change in musical style. Young could change styles in an instant—as on the Nat Cole/Buddy Rich trio version of “I Want to Be Happy”—and his comments in published interviews indicate the willingness to switch up his style as the mood struck. Taking in all of the small group material, including Jones/Smith and the Commodore Kansas City Six session (which appear before and in the midst of the Decca sides, respectively), the Mosaic box offers a wide spectrum of Young’s combo sides.

The Victor session of March 10, 1941 pairs Young’s combo (co-led with his brother, Lee Young) with Una Mae Carlisle, a vocalist and pianist best known for her musical association with Fats Waller. Carlisle was a passable singer, but the best moments of these sides belong to Lester, who displays a rich tone and thoughtful solos. He uses silence effectively, and under his direction, the group plays all four titles at a reduced volume with relaxed tempos. The focus and inspiration that permeates the Victor session is almost completely missing from Young’s performances on the Sammy Price session recorded the following month. Schoenberg speculates on reasons why Young sounds professional but uninspired here, but it’s entirely possible that something non-musical was the reason for Young’s lackluster performance. The July 1942 trio recordings with pianist Nat Cole and bassist Red Callender are full of delights and surprises. Working with the harmonically-progressive Cole, Young takes great care to outline and delineate the underlying harmonies, and Callender’s bass lines are quite exploratory in this pre-bop session. The interaction between these three musicians is spectacular throughout and the remastered sound by Andreas Meyer brings out more of the original sound than any other transfers I’ve heard of this well-known material.

Any suspicion that Young was mellowing his approach is quickly dispelled with his phenomenal four-chorus solo on the Dicky Wells-led 1943 version of “I Got Rhythm”. Young charges like a racehorse through this solo, and as fellow tenor saxophonist Schoenberg notes, he doesn’t rely on his usual pet phrases to get through the harmonic sequence. The entire session is marvelous, with the underrated trumpeter Bill Coleman contributing lovely open horn solos and Wells offering commanding improvisations. Young is in spectacular form throughout, and the rhythm section of Ellis Larkins, Freddie Green, Al Hall and Jo Jones provide peerless support. A week later, Young was back in the studios to record his first session for Keynote. This quartet session has long been praised as a masterpiece, and with good reason. The rhyt hm section of Johnny Guarnieri, Slam Stewart and Sid Catlett was flexible enough to incorporate some of the interactive elements of bop without destroying the smooth swing feel that Young loved. As on the previous session, Young is in total control with an assertive tone, rhythmic acuity, and unmatched—even by him!—melodicism. “Sometimes I’m Happy” and “Afternoon of a Basie-ite” are probably the best-known sides from this session, but everything this quartet played that day (including the breakdowns) remains fascinating.

hm section of Johnny Guarnieri, Slam Stewart and Sid Catlett was flexible enough to incorporate some of the interactive elements of bop without destroying the smooth swing feel that Young loved. As on the previous session, Young is in total control with an assertive tone, rhythmic acuity, and unmatched—even by him!—melodicism. “Sometimes I’m Happy” and “Afternoon of a Basie-ite” are probably the best-known sides from this session, but everything this quartet played that day (including the breakdowns) remains fascinating.

The Kansas City Seven date (for Keynote) and the Kansas City Six session (for Commodore) were recorded six days apart in March 1944, and they feature similar personnel: Buck Clayton or Bill Coleman on trumpet, Dicky Wells on trombone, Young on tenor, Basie or Joe Bushkin on piano, Freddie Green (on the Keynote session only), Rodney Richardson or John Simmons on bass, and Jo Jones on drums. Young had rejoined Basie a few months earlier, but the only recordings of the big band are transcription and broadcast recordings. Schoenberg writes that Young wasn’t particularly inspired in those recordings. That is not the case with either of these sessions. While Young’s tone is noticeably hoarser and deeper on the Keystone session, he shows his rhythmic and melodic mastery throughout the date (On the incomplete take of “Six Cats and a Prince”, Young’s rhythmic manipulation nearly leads the Basie rhythm section to turn around the beat!). “Lester Leaps Again” is an unfortunate name for a very good performance. Young plays a fine opening solo and he plays great exchanges with Basie, but that’s basically all that this performance has in common with the 1939 “Lester Leaps In”. The tempo is slower in 1944 than 5 years earlier, and the harmonic progression was “I Got Rhythm” in 1939 and a 12-bar blues on the “remake”. The slower tempo and Young’s different tone could lead listeners to believe that Young was on the decline and uninspired, but by listening to the music in context of the contemporary sessions, it’s obvious that Young was still playing very well at this stage of his career. The master takes of the Commodore session nearly equal the Keynote, but an interesting thing happens on the alternate takes of “Three Little Words”: Young again manipulates the rhythm in his solos, but the Bushkin/Simmons/Jones rhythm section has a hard time maintaining the tempo. Without the stabilizing force of Freddie Green, the pulse falls dramatically during Young’s solos. By the time they cut the master take, the problem had been resolved, but I suspect Jones (who was accustomed to Young’s rhythmic games) had to whip the others into shape! Certainly, Jones plays more forcefully here than on any other session on this set.

It would be another 19 months before Young entered into another recording studio. He had just been discharged from the Army, and the sessions he made for Aladdin/Philo have long been cited as proof of the damage the military inflicted on Young. The actual recordings show this to be a complete fallacy: the last side from the March 1944 Commodore date, “Four O’Clock Drag” sounds much more dispirited than “D.B. Blues” recorded at the first Aladdin session in December 1945. The tonal and emotional characteristics that Young brought to these pieces were creative decisions, and not necessarily a reflection of his mental state. The high quality of the music on the initial Aladdin session (including the exquisite “These Foolish Things”) stands as a testament to Young’s strengths as a person and a musician. How many others could rebound this well? A reunion with Helen Humes—probably recorded shortly after the “D.B. Blues” session—features Young’s atmospheric obbligato on “He Don’t Love Me Anymore” and soulful solos on “Pleasing Man Blues” and “Riffin’ Without Helen” (the personnel also includes Snooky Young, who surprises with his fiery trumpet solos). Young’s next session features his classic solo on “It’s Only a Paper Moon”—later lyricized by Eddie Jefferson—and a rhythmically forceful version of “Lover Come Back to Me”. The other tracks are slightly less successful, including a speedy version of “After You’ve Gone”, which has a few shaky spots at the beginning and a strange ending, and “Jammin’ with Lester”, which veers close to R&B and has a few rough honks from Young’s that he would have played with a little more refinement a few years earlier.

The 1946 trio session with Young, Nat Cole and Buddy Rich is a highpoint in the discographies of all three participants. It must have be strange when the musicians realized that Norman Granz had not hired a bass player for the session; it’s a treat to listen to this session in sequence to hear how Young, Cole and Rich adapted to the unusual instrumentation of tenor, piano and drums. Schoenberg details these changes in the notes, pointing out Cole’s use of the piano’s low register, Rich’s admirable self-control and Young’s increasing confidence. I don’t hear the abstractionism Schoenberg does in “Back to the Land”, but I am equally impressed by the performance. The brilliant rhythmic play on “I Found a New Baby” is a delight, as is the sensitive Young/Cole duet on “Peg O’ My Heart”. If I had to pick just one highlight from this session, it would have to be the previously mentioned “I Want to Be Happy”, which features one of Young’s finest solos (and one that seems to spring up out of nowhere). I’ve loved these recordings for years, and I still find new surprises every time I listen again (Was that a little of “In a Mist” that Cole quoted in the last bridge of “Mean to Me”?).

The final disc of the Mosaic set wraps up with Young’s Aladdin recordings from 1946 and 1947. With the exception of the Helen Humes session discussed above, Young was the leader on all of the Aladdin sides, and it’s interesting to see him working with many of the young boppers. Howard McGhee, Dodo Marmarosa, Red Callender and Curtis Counce turn up on the earlier sessions, while Shorty McConnell, Joe Albany, Sadik Hakim, Chuck Wayne, Curly Russell and Chico Hamilton appear later in the series, and each musician finds his own way to balance bop and swing styles. On occasion, one can hear Young incorporating a bop idea into his style as well, which brings up a chicken-and-egg puzzle: On “S.M. Blues”, Young improvises a series of upwardly modulating blues choruses; years later, McGhee used the idea on recordings and live performances, but was it Young’s idea first? Young’s ballads are captivating, with his “She’s Funny That Way” later becoming the subject of a Kurt Elling lyric, and his unusually-slow rendition of “On the Sunny Side of the Street” offering a new perspective on the classic song. On medium and up tempo numbers, he keeps pace—and at times excels—his young sidemen, who were used to playing at the upper ends of the tempo scale. Young’s sound is heavier and rougher than in earlier days, but his spirits seem high and he navigates around his horn with the same ease that he had a dozen years before. Unfortunately, the final session does not show Young in the best light: his intonation fails him, his sound is weak and his ideas are unfocused. Again, there are a number of things—many of them non-musical—that could have affected Young’s performance, and we simply can’t be sure of why this session misfired (Charlie Carpenter’s quote in the final paragraphs of the Mosaic notes notwithstanding).

Nearly 60 years after his passing, Lester Young remains one of the icons of jazz history. Terribly misunderstood during his lifetime, his career was hampered by copycat musicians (one of whom reportedly said to Lester’s face, “I play you better than you play you”), jazz critics who ascribed Young’s personal setbacks as signs of a decline that was basically non-existent, and his own sensitive personality, which seemed ill-matched to the usually heartless music business. The current packages by Mosaic and the Jazz Museum in Harlem help to set the record straight on Young’s recordings, and offer the unique opportunity to hear related songs and sessions back-to-back. There could be no greater honor for such a great American artist.