Tribute albums are nothing new in jazz. Unfortunately, the majority of these albums are commercially-motivated recordings designed to increase sales and deliver more nostalgia than good music. However, at its base, the tribute album is the most personal of all recording projects, since the performer is usually performing music of their own influences. Many tributes try to recreate the instrumentation and sound of an older band, but that approach can only go so far. In their most recent releases, clarinetist Anat Cohen and saxophonist Joe Lovano go directly to the music of their mentors and re-interpret it to create unique memorials.

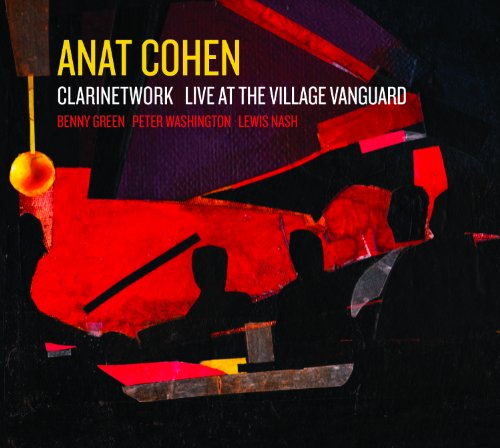

The outside cover of Cohen’s “Clarinetwork: Live at the Village Vanguard” (Anzic 1203) is not marked as a Benny Goodman tribute, but the introduction of the opening “Sweet Georgia Brown” makes the subject clear. It is a 7/4 adaptation of the introduction of the Goodman Sextet number, “Seven Come Eleven”. Through the opening exposition and the first few bars of her clarinet solo, it sounds like Cohen and her trio are taking the safe route, playing straight-ahead version of old Goodman chestnuts. But then Cohen plays a figure that moves outside of the chord changes,  and that signals the whole band to explore the outer reaches of these songs. From then on, “Clarinetwork” is a wild ride, constantly re-examining the standard approaches to this repertoire. Cohen plays clarinet throughout, accompanied by three musicians with whom she had never played in public: pianist Benny Green, bassist Peter Washington and drummer Lewis Nash. In her brief liner notes, Cohen states that the group “had no preconceptions about the material”. I’m not sure if the group rehearsed this music before the performance, but it is clear that they shared the desire to make this music their own. They accomplish this goal, not just through adventurous solos and extended harmonies, but by playing this music with conviction in their own musical language. Green seems to embody every style of modern jazz piano, but combines them in a unique way to establish his own identity. Washington and Nash drive the band with great abandon and their inventive solos show why they are first-call players in New York (According to Tom Lord’s “Jazz Discography”, Nash is also the scat vocalist on “St. Louis Blues”). But it is Cohen that is most remarkable. Her clarinet style has been said to be equally derived from modern jazz and klezmer music, yet her playing here displays a deep knowledge of classic jazz clarinet. Whether on the bubbling low-register arpeggios on “Body and Soul” or the wailing altissimo sounds on “St. James Infirmary”, she manages to evoke the spirit of Benny Goodman without abandoning her own musical vocabulary. In the notes, she calls the Village Vanguard a sacred place where spirits of the past visit and watch. One must assume that Goodman’s spirit was there, and approving heartily.

and that signals the whole band to explore the outer reaches of these songs. From then on, “Clarinetwork” is a wild ride, constantly re-examining the standard approaches to this repertoire. Cohen plays clarinet throughout, accompanied by three musicians with whom she had never played in public: pianist Benny Green, bassist Peter Washington and drummer Lewis Nash. In her brief liner notes, Cohen states that the group “had no preconceptions about the material”. I’m not sure if the group rehearsed this music before the performance, but it is clear that they shared the desire to make this music their own. They accomplish this goal, not just through adventurous solos and extended harmonies, but by playing this music with conviction in their own musical language. Green seems to embody every style of modern jazz piano, but combines them in a unique way to establish his own identity. Washington and Nash drive the band with great abandon and their inventive solos show why they are first-call players in New York (According to Tom Lord’s “Jazz Discography”, Nash is also the scat vocalist on “St. Louis Blues”). But it is Cohen that is most remarkable. Her clarinet style has been said to be equally derived from modern jazz and klezmer music, yet her playing here displays a deep knowledge of classic jazz clarinet. Whether on the bubbling low-register arpeggios on “Body and Soul” or the wailing altissimo sounds on “St. James Infirmary”, she manages to evoke the spirit of Benny Goodman without abandoning her own musical vocabulary. In the notes, she calls the Village Vanguard a sacred place where spirits of the past visit and watch. One must assume that Goodman’s spirit was there, and approving heartily.

“Bird Songs” (Blue Note 5861) by Joe Lovano and Us Five pays homage to Charlie Parker with radically new approaches to his compositions. “Passport” becomes a jazz rondo, with recurring melody statements and abrupt tempo changes. “Donna Lee”, usually played at breakneck speed, is played as a ballad over a fascinating dialogue by the group’s two drummers Otis Brown, III and Francisco Mela. “Blues Collage” is a brilliant combination of Parker’s blues themes, with Lovano playing “Carving The Bird” on straight alto at the same time that pianist James Weidman and bassist Esperanza Spalding play “Bloomdido” and “Bird Feathers”, respectively. As Lovano points out in the notes, the end result is a performance reminiscent of the Modern Jazz Quartet. Considering that John Lewis was both the musical director of the MJQ and a recurring member of Parker’s quintet, this means that Lovano is channeling Parker’s influence from a primary and secondary source! Of course, Parker lies deep within Lovano’s solo style, and I find traces of it in the way he phrases away from the standard 4-bar mileposts, and in his manner of dropping quotes in the most unusual places. Another way that Parker’s spirit is summoned is in the contrast between Lovano and Weidman. In several instances, Weidman plays the Miles Davis role to Lovano’s Parker, offering clear single line piano solos in contrast to the dense intricate inventions of the saxophonist. Spaulding is a rock throughout the album, providing a necessary anchor against the interplay of the drummers while providing creative bass lines and several inventive solos. Lovano unveils a pair of unique new instruments, a mezzo soprano saxophone with a noticeably richer sound than soprano, and the aulochrome, a type of double-barreled soprano that allows Lovano to play harmonies on the same instrument. On the latter horn, Lovano offers “Birdyard”, a stunning two-minute showcase that evokes the quarter-tone music of the Middle East. Lovano ponders what Parker would have done with such an instrument, but the greater question must be how Parker’s music will survive in the 21st century. The jazz world must not be satisfied with versions of historic music that binds itself to the original concept. If nothing else, jazz is a music that breathes and expands with every new performance. The old recordings can show us what it used to sound like; our responsibility is to make it sound fresh.

“Blues Collage” is a brilliant combination of Parker’s blues themes, with Lovano playing “Carving The Bird” on straight alto at the same time that pianist James Weidman and bassist Esperanza Spalding play “Bloomdido” and “Bird Feathers”, respectively. As Lovano points out in the notes, the end result is a performance reminiscent of the Modern Jazz Quartet. Considering that John Lewis was both the musical director of the MJQ and a recurring member of Parker’s quintet, this means that Lovano is channeling Parker’s influence from a primary and secondary source! Of course, Parker lies deep within Lovano’s solo style, and I find traces of it in the way he phrases away from the standard 4-bar mileposts, and in his manner of dropping quotes in the most unusual places. Another way that Parker’s spirit is summoned is in the contrast between Lovano and Weidman. In several instances, Weidman plays the Miles Davis role to Lovano’s Parker, offering clear single line piano solos in contrast to the dense intricate inventions of the saxophonist. Spaulding is a rock throughout the album, providing a necessary anchor against the interplay of the drummers while providing creative bass lines and several inventive solos. Lovano unveils a pair of unique new instruments, a mezzo soprano saxophone with a noticeably richer sound than soprano, and the aulochrome, a type of double-barreled soprano that allows Lovano to play harmonies on the same instrument. On the latter horn, Lovano offers “Birdyard”, a stunning two-minute showcase that evokes the quarter-tone music of the Middle East. Lovano ponders what Parker would have done with such an instrument, but the greater question must be how Parker’s music will survive in the 21st century. The jazz world must not be satisfied with versions of historic music that binds itself to the original concept. If nothing else, jazz is a music that breathes and expands with every new performance. The old recordings can show us what it used to sound like; our responsibility is to make it sound fresh.