By the time he left the Miles Davis Quintet in the spring of 1960, John Coltrane had already laid the foundation for his newest style. Jettisoning the complex chord changes he had explored on “Giant Steps“, Coltrane developed a sophisticated approach to modal playing. His early exposure to modes came on his appearances on George Russell‘s all-star album, “New York, NY” and the Davis albums “Milestones” and “Kind of Blue“. With his ground-breaking recording of Richard Rodgers‘ “My Favorite Things“, Coltrane and his band transformed an innocuous show tune into a hypnotic incantation. The core of the Coltrane Quartet’s sound could be heard throughout the “Favorite Things” album: long, highly intense saxophone solos over quartal harmonies on piano, a droning bass line, and explosive, interactive drums. Coltrane seemed to find the right musicians to realize these new rhythm section roles, and for the “Favorite Things” sessions, he had found two of those players: pianist McCoy Tyner and drummer Elvin Jones. It took a little longer to find the right bassist, but Coltrane brought several gifted players into his band, all of whom could play some form of the drone. In the late spring and summer of 1961, Coltrane had two bassists in the group, Art Davis and Reggie Workman, and they would split duties, with one droning in the low register, and the other improvising lines in the top register. There was one more musician who occasionally worked with Coltrane during this period: reedman Eric Dolphy, who as Coltrane said, found a new way to express the same thing we had found one way to do. After he sat in, we decided to see what it would grow into.

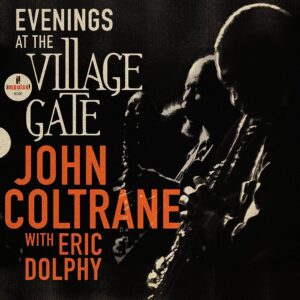

As we can hear in their albums “Africa/Brass“, “Olé“, and the collected recordings from the Village Vanguard, Dolphy brought a contrasting voice to the group, along with a wide range of instrumental colors, and  a focused approach to the group’s live performances. Adding to the impressive discography above, Impulse has just released a newly-discovered recording of the Coltrane group from August 1961. “Evenings at the Village Gate” contains five tracks, all recorded shortly before Dolphy left for a European tour. Typical of Coltrane’s live albums, the track timings range from 10 to 22 minutes, but the difference on this disc is that Coltrane realized that he was sharing the front line with a fellow musician who also liked to stretch out. Coltrane’s solos carry the same intensity as his other recordings, but here that energy is compacted into a shorter timeframe. Jones also adapts to Dolphy’s presence as he plays with less density behind Dolphy’s flute and bass clarinet on the first two tracks, “My Favorite Things” and “When Lights are Low”, before ramping things up for Coltrane’s soprano sax. However, starting with the third track, “Impressions”, Jones plays with full force behind both horn players without drowning out either one.

a focused approach to the group’s live performances. Adding to the impressive discography above, Impulse has just released a newly-discovered recording of the Coltrane group from August 1961. “Evenings at the Village Gate” contains five tracks, all recorded shortly before Dolphy left for a European tour. Typical of Coltrane’s live albums, the track timings range from 10 to 22 minutes, but the difference on this disc is that Coltrane realized that he was sharing the front line with a fellow musician who also liked to stretch out. Coltrane’s solos carry the same intensity as his other recordings, but here that energy is compacted into a shorter timeframe. Jones also adapts to Dolphy’s presence as he plays with less density behind Dolphy’s flute and bass clarinet on the first two tracks, “My Favorite Things” and “When Lights are Low”, before ramping things up for Coltrane’s soprano sax. However, starting with the third track, “Impressions”, Jones plays with full force behind both horn players without drowning out either one.

The repertoire is interesting too. “Lights” was not a part of the group’s book, but was added as a feature for Dolphy. “Favorite Things” and “Impressions” were established staples, but “Greensleeves” was a little too similar to “Favorite Things” and the band seems rather bored with playing in waltz time over a single mode. Tyner and Dolphy reprise the “Things” motive of playing the melody in the middle of their solos and then launching into another improvisation. When Coltrane enters for his solo, he sounds angry and frustrated, as he repeats a motive several times over, as if he is trying to beat the idea to death. The closing track, “Africa” had been part of the quartet’s book for several months. Coltrane and Dolphy collaborated on an Impulse recording of the piece with a brass/reed ensemble two months earlier (“Olé”, which bears several similarities to “Africa”, was recorded for Atlantic between the two “Africa/Brass” sessions for Impulse). Dolphy was the arranger and conductor for “Africa/Brass”, and while he played within the ensemble, he did not solo on “Africa”. On the Village Gate recording, the usually confident saxophonist seems unsure of what to play over the single-chord vamp. After a couple of minutes of rather aimless ideas, he wails on a single pitch over the churning rhythm. Everyone else seemed fine with the piece, and while the memorable bowed bass passage was not repeated here, Coltrane’s powerful tenor solo is one of the highlights of the album.

A few words about the recording. It was made by Rich Alderson, who was the newly-hired sound engineer at the Village Gate. Having just installed a state-of-the-art sound system for the club, Alderson was curious about how it sounded. Without telling anyone–including Coltrane, the band, or club owner Art D’Lugoff—Alderson hung a single RCA microphone above the stage and connected it to an open reel tape recorder. Alderson was a student of the master engineer Robert Fine, who had produced extraordinary recordings of orchestras and wind ensembles using a single overhead microphone. Meanwhile, over at Vanguard Records, John Hammond and company owners Maynard and Seymour Solomon used Fine’s minimalist recording approach for their acclaimed Jazz Showcase albums. The single-mic method was very effective in obtaining a natural balance of instruments (although Vanguard mayhave added accent microphones for the bass and rhythm guitar, because they were faintly recorded by the overhead mic). What a single-mic setup could not do was fix balance issues on the stage. If an instrument was muffled or indistinct, there was nothing that could be done with the microphone to correct the problem. All of which makes it very interesting when Tyner’s piano—nearly inaudible for the CD’s first 25 minutes—suddenly appears in clear, bright fidelity! What happened? Alderson was running the house sound system for the show, and when Tyner began to solo, Alderson turned up the stage microphone located in or near the piano. The sound came through the house speakers and was subsequently picked up by the recording microphone! Alderson left the United States during Richard Nixon’s presidency, and before he left, he placed this tape and several others in the care of the Institute of Sound, a non-profit organization based at Carnegie Hall. While Alderson was away, the curator of the Institute passed away, and the tapes were donated to the New York Public Library. It took Alderson years to discover what happened to his long-lost tapes.

The re-discovery of this historic recording of John Coltrane at the Village Gate reveals an important chapter of the Coltrane Quartet’s evolution. The revolutionary style that would soon become second nature to Coltrane, Tyner, Jones, and the eventual permanent bassist Jimmy Garrison, was still in development during that summer engagement at the Gate. By the time Dolphy rejoined the group for the Village Vanguard dates, the music was stronger and tighter than ever. If the Village Gate disc is not the classic album that the Village Vanguard LP was, it was a crucial and necessary step toward greatness.