Time is an essential element of many types of art, including music, movies, and theatre. Any type of movement in the performing arts takes place against the framework of the clock. Orchestral musicians must play their parts in strict relationship to a pulse set by the conductor, while stage actors have time cues for their entrances and exits. Film and videotaped performances are edited through a precise frame count, with each frame taking 1/24th of a second on film or 1/30th of a second on videotape. Even visual art evokes time in the way the clock is frozen. What brought those lonely diners into Edward Hopper‘s “Nighthawks“? What happened after Alfred Eisenstaedt caught the sailor and nurse kissing in Times Square?

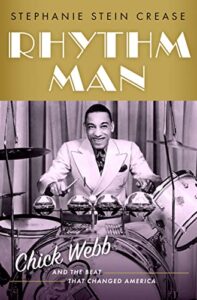

There are several facets of time present in Stephanie Stein Crease‘s new biography of Swing Era drummer Chick Webb. The book’s title, “Rhythm Man” (Oxford) refers to Webb’s unique way of syncopating patterns across the ground beat. Like many drummers, Webb was said to have excellent time; that is, the ability to set and maintain a steady tempo, even when the off-beat patterns cause musicians to rush. The long progression of time is also a key element of Crease’s book. Written over 80 years after Webb’s death, with nearly everyone who knew or worked with Webb deceased, Crease undertook a tremendous amount of original research to close the gaps in Webb’s story. The combination of that meticulous study with Crease’s skillful storytelling creates a triumph over time, making us believe—beyond all reason—that Crease was actually there in Baltimore 110 years ago as the young and disabled Webb was playing rhythms on the tin cans he found in the streets.

There are several facets of time present in Stephanie Stein Crease‘s new biography of Swing Era drummer Chick Webb. The book’s title, “Rhythm Man” (Oxford) refers to Webb’s unique way of syncopating patterns across the ground beat. Like many drummers, Webb was said to have excellent time; that is, the ability to set and maintain a steady tempo, even when the off-beat patterns cause musicians to rush. The long progression of time is also a key element of Crease’s book. Written over 80 years after Webb’s death, with nearly everyone who knew or worked with Webb deceased, Crease undertook a tremendous amount of original research to close the gaps in Webb’s story. The combination of that meticulous study with Crease’s skillful storytelling creates a triumph over time, making us believe—beyond all reason—that Crease was actually there in Baltimore 110 years ago as the young and disabled Webb was playing rhythms on the tin cans he found in the streets.

With the help of contemporary reports from the Black press, and surviving historical documents including medical records and census reports, Crease paints a vivid picture of Webb’s childhood in East Baltimore. She clarifies that it was a case of spinal tuberculosis that stunted Webb’s growth, twisted his spine, and gave his back an unsightly hump. The support from his family came through his single mother and siblings, and it was extended to a boarder who became a surrogate (but unrelated) grandfather. Webb remained close to his family, and made frequent visits home, even after becoming one of the Swing Era’s best-known musicians. His ever-deteriorating health caused him to take long stays at Johns Hopkins, as the doctors tried to make Webb as comfortable as possible.

By 1925, the teenaged Webb had developed an enviable reputation in his hometown. Webb and his close friend, guitarist John Trueheart, decided to move to New York City. They scuffled for several years but eventually worked their way into the Harlem jazz community. Webb attended jam sessions and concerts across the neighborhood learning the various techniques of established drummers. Fortunate enough to be on the scene just as the major jazz orchestras were emerging, Webb picked up what he could from others and combined it with his own progressive imagination. In the first few years of Webb’s Harlem residency, a number of new venues opened that featured Black musicians playing for Black audiences. One of these venues was the Savoy Ballroom, which eventually became the ongoing New York engagement for the Chick Webb Orchestra. But it took many years of struggle and development before Webb landed that prime gig.

Crease takes the majority of her nearly 300-page book to detail Webb’s professional life before Ella Fitzgerald joined the band and catapulted it to its greatest popularity. Webb’s earliest orchestras were “stomp” bands, and while they excelled at playing this older style, Webb longed for a higher ideal. The adaptations he made to his rhythmic patterns became part of the language of swing. Since Webb couldn’t conduct while playing the drums, he created a large vocabulary of percussive effects which doubled as band cues. These developments were highly influential in their day. Papa Jo Jones, long considered the epitome of swing drummers, unequivocally stated that his adaptation of Webb’s techniques was an essential part of his own style. Later jazz percussion masters including Kenny Clarke and Max Roach also studied Webb’s methods, and their acknowledgments of Webb’s influence can be found within Crease’s narrative. In fact, whether they realize it or not, many current big band drummers play patterns that can be traced back to Chick Webb.

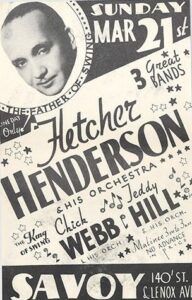

The weekly pay for musicians at the Savoy Ballroom wasn’t great, but once Webb landed his residency there, he attracted many outstanding sidemen, including Benny Carter, Mario Bauza, Edgar Sampson, and Louis Jordan. The band was very loyal to Webb, and their dedication translated into exalted musicianship. The Savoy hosted band battles on a regular basis, and more often than not, the Webb orchestra emerged victorious, even when facing competition like the Fletcher Henderson, Benny Goodman, and Count Basie orchestras. Through live radio broadcasts, recordings, and performance tours, Webb’s orchestra was one of the most highly-regarded of the early big bands.

Louis Jordan. The band was very loyal to Webb, and their dedication translated into exalted musicianship. The Savoy hosted band battles on a regular basis, and more often than not, the Webb orchestra emerged victorious, even when facing competition like the Fletcher Henderson, Benny Goodman, and Count Basie orchestras. Through live radio broadcasts, recordings, and performance tours, Webb’s orchestra was one of the most highly-regarded of the early big bands.

Webb’s discovery and support for Ella Fitzgerald caused subtle changes in the band’s direction. Even at this early stage of her career, Fitzgerald could swing rhythm as well as anyone in the band, and the band continued to play hot jazz arrangements on every set. In her search for unique material, Fitzgerald collaborated with Van Alexander to create a swing version of the nursery rhyme, “A-Tisket, A-Tasket“. The record was a huge hit, but it led to a number of inferior sequels. However, as Crease points out, the flip side of that 78 was “Liza“, a fast and energetic instrumental arrangement of the Gershwin standard, with one of Webb’s most astounding solos. The novelty song may have sold records and raised the band’s profile, but the B-side displayed the band’s passion and spirit.

The band’s newfound success fulfilled Webb’s long-term goals, but he had little time left to reap the benefits. His illness continued to worsen, and he called in other drummers to sub for him when he could no longer play complete sets. By early 1939, he missed significant sections of his band’s tour because of extended hospitalizations. It was during one of those absences when Webb succumbed to his illness. He was only 39 years old at his passing. Webb’s funeral was a massive event in East Baltimore, with a teary-eyed Fitzgerald singing “My Buddy” to her late mentor. The Webb band continued under Fitzgerald’s leadership until 1942. Her fame multiplied many times over as a solo jazz artist, but she always credited Webb for giving her career a great beginning.

As a long overdue biography of a highly influential jazz icon, “Rhythm Man” is instantly essential jazz literature. Crease’s affection for her chosen topic speaks directly to the reader and her sensitive descriptions of Webb’s musical triumphs over his painful illness increase our understanding of his unending bravery. At the end of the book, the final element of time will reveal itself, as inspired readers invest their time to investigate Webb’s recordings and reconsider his important role in the development of jazz drumming and the big bands. Let us celebrate Chick Webb and all of the wonderful music he left for us.