FRANCO AMBROSETTI WITH STRINGS: “NORA” (Enja 9811)

In a note within the booklet for his new album “Nora”, Swiss trumpeter Franco Ambrosetti writes that recording an album with strings has been his goal since he became a professional musician in 1961. He made his first attempt in 1979 on an album with the string orchestra of the Scala of Milan, along with several American jazz musicians as guest artists. It took over four decades to try again, but “Nora” reveals Ambrosetti at his most poised and thoughtful. The title composition, which Ambrosetti dedicated to his wife, has a simple, elegant melody, and Ambrosetti does not embellish it in the least during the theme statement. Nor does his ensuing solo overflow with extravagant variations or filigrees. He leaves the major development to arranger/conductor Alan Broadbent, who supplies a richly-colored ensemble chorus for the strings (led by violinist Sara Caswell). John Scofield plays the introduction and shares the melody chorus of George Gruntz’s “Morning Song of a Spring Flower” with Ambrosetti’s flugelhorn, as the strings ebb and flow with a strong countermelody. Obviously inspired by the setting, Scofield plays a beautifully-crafted solo, with Ambrosetti following with a fine statement of his own. The strings conclude the arrangement with a gorgeous extended passage. “All Blues”—with the strings enhancing the parts originally played by John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley—has excellent solos by Ambrosetti, and pianist Uri Caine, with outstanding support from solid bassist Scott Colley and redoubtable drummer Peter Erskine. The strings swing (!) through a three-chorus variation before Ambrosetti returns for the closing theme and fade-out. Victor Feldman’s touching ballad “Falling in Love” was never recorded by its composer, and is probably best known from a 1986 Stan Getz recording. Given proper airplay, Ambrosetti’s glorious recording could restore interest in this nearly-forgotten gem. It is followed by one of the slowest versions of “Autumn Leaves” I’ve ever heard. The crawling pace lets Ambrosetti bring out the song’s deep melancholy, and the strings amplify those feelings through Broadbent’s outstanding score. Ambrosetti’s only original composition on the album, “Sweet Journey” opens with an ethereal solo by Caswell, which is contrasted by Ambrosetti’s middle-register theme and variation, and a sparkling improvisation by Caine. Ambrosetti told annotator Bill Milkowski I arrived home from Greece one day and sat at my new beautiful Steinway, that [my wife] Silli had just given me. I played those first four notes, and it instantly triggered something. From that moment, it became what it is. John Dankworth’s “It Happens Quietly” is another composition by an English jazz artist that is still underplayed by contemporary musicians. Ambrosetti’s romantic version stands well alongside the recording made by John and his daughter Jacqui on the last album they made together. The album concludes with a highly atmospheric setting of John Coltrane’s “After the Rain”. The glorious recording was engineered by Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz, who were also responsible for the audio miracles found on the next disc in this survey. (However, I question the disc format: why issue this the very rarely used hybrid SACD format instead of a dual-layer DVD? I don’t know anyone who owns—or owned—an SACD player and DVD players have surround circuitry built into them. Considering all of the fine work they do creating surround sound albums, it would be beneficial for them if more people could listen to them.)

In a note within the booklet for his new album “Nora”, Swiss trumpeter Franco Ambrosetti writes that recording an album with strings has been his goal since he became a professional musician in 1961. He made his first attempt in 1979 on an album with the string orchestra of the Scala of Milan, along with several American jazz musicians as guest artists. It took over four decades to try again, but “Nora” reveals Ambrosetti at his most poised and thoughtful. The title composition, which Ambrosetti dedicated to his wife, has a simple, elegant melody, and Ambrosetti does not embellish it in the least during the theme statement. Nor does his ensuing solo overflow with extravagant variations or filigrees. He leaves the major development to arranger/conductor Alan Broadbent, who supplies a richly-colored ensemble chorus for the strings (led by violinist Sara Caswell). John Scofield plays the introduction and shares the melody chorus of George Gruntz’s “Morning Song of a Spring Flower” with Ambrosetti’s flugelhorn, as the strings ebb and flow with a strong countermelody. Obviously inspired by the setting, Scofield plays a beautifully-crafted solo, with Ambrosetti following with a fine statement of his own. The strings conclude the arrangement with a gorgeous extended passage. “All Blues”—with the strings enhancing the parts originally played by John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley—has excellent solos by Ambrosetti, and pianist Uri Caine, with outstanding support from solid bassist Scott Colley and redoubtable drummer Peter Erskine. The strings swing (!) through a three-chorus variation before Ambrosetti returns for the closing theme and fade-out. Victor Feldman’s touching ballad “Falling in Love” was never recorded by its composer, and is probably best known from a 1986 Stan Getz recording. Given proper airplay, Ambrosetti’s glorious recording could restore interest in this nearly-forgotten gem. It is followed by one of the slowest versions of “Autumn Leaves” I’ve ever heard. The crawling pace lets Ambrosetti bring out the song’s deep melancholy, and the strings amplify those feelings through Broadbent’s outstanding score. Ambrosetti’s only original composition on the album, “Sweet Journey” opens with an ethereal solo by Caswell, which is contrasted by Ambrosetti’s middle-register theme and variation, and a sparkling improvisation by Caine. Ambrosetti told annotator Bill Milkowski I arrived home from Greece one day and sat at my new beautiful Steinway, that [my wife] Silli had just given me. I played those first four notes, and it instantly triggered something. From that moment, it became what it is. John Dankworth’s “It Happens Quietly” is another composition by an English jazz artist that is still underplayed by contemporary musicians. Ambrosetti’s romantic version stands well alongside the recording made by John and his daughter Jacqui on the last album they made together. The album concludes with a highly atmospheric setting of John Coltrane’s “After the Rain”. The glorious recording was engineered by Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz, who were also responsible for the audio miracles found on the next disc in this survey. (However, I question the disc format: why issue this the very rarely used hybrid SACD format instead of a dual-layer DVD? I don’t know anyone who owns—or owned—an SACD player and DVD players have surround circuitry built into them. Considering all of the fine work they do creating surround sound albums, it would be beneficial for them if more people could listen to them.)

JANE IRA BLOOM: “PICTURING THE INVISIBLE: FOCUS 1” (Outline—digital only)

In 1984, soprano saxophonist Jane Ira Bloom recorded a marvelous album with pianist Fred Hersch. Titled “As One”, it was recorded digitally but originally issued only on LP. When a CD edition was released in 2001, I listened to it on headphones, and through the CD’s increased clarity (and lack of surface noise) I discovered that it was actually a trio record: Jane, Fred, and the room. The hardwood surfaces in the studio reflected sounds from the two instruments, creating a remarkable three-way conversation. I suspect that Bloom and her recording engineers Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz might have achieved the same result if “Picturing the Invisible” had been recorded before the pandemic. When isolation became the norm, Anderson and Schwarz found new solutions which allowed each of the four musicians on the project—located in their homes and offices in the New York City metro area—to improvise together in real-time. Latency, the sound delays usually encountered when trying to record music over the internet, was eliminated, and Schwarz brought portable equipment to each sideperson’s location, while remote controlling the recording equipment located in Bloom’s office. As reproduced on a burned DVD with 96kHz/24-bit sound, the surround effect is stunning, even though the room acoustics could only reflect the sole musician occupying them. On the four duets Bloom recorded with drummer Allison Miller, the two instruments are perfectly synchronized, which allows Miller to be an active duet partner. Bloom’s original compositions might be better-termed sketches or scenarios, but those pieces recorded with Miller appear to have established formal structures and melodic themes. The works recorded with bassist Mark Helias and koto player Miya Masaoka are a little looser. Both of these players seem to be there to react to Bloom’s improvisations, and neither finds the opportunity to lead (at least, that’s how it sounds to me). With COVID seemingly in its last phases, I expect that Bloom will return to regular recording and performing and that these compositions will return in larger settings. Perhaps there might be a “Focus 2” recording that records all of the musicians in the same recording space and presents the music within its original concept.

but originally issued only on LP. When a CD edition was released in 2001, I listened to it on headphones, and through the CD’s increased clarity (and lack of surface noise) I discovered that it was actually a trio record: Jane, Fred, and the room. The hardwood surfaces in the studio reflected sounds from the two instruments, creating a remarkable three-way conversation. I suspect that Bloom and her recording engineers Jim Anderson and Ulrike Schwarz might have achieved the same result if “Picturing the Invisible” had been recorded before the pandemic. When isolation became the norm, Anderson and Schwarz found new solutions which allowed each of the four musicians on the project—located in their homes and offices in the New York City metro area—to improvise together in real-time. Latency, the sound delays usually encountered when trying to record music over the internet, was eliminated, and Schwarz brought portable equipment to each sideperson’s location, while remote controlling the recording equipment located in Bloom’s office. As reproduced on a burned DVD with 96kHz/24-bit sound, the surround effect is stunning, even though the room acoustics could only reflect the sole musician occupying them. On the four duets Bloom recorded with drummer Allison Miller, the two instruments are perfectly synchronized, which allows Miller to be an active duet partner. Bloom’s original compositions might be better-termed sketches or scenarios, but those pieces recorded with Miller appear to have established formal structures and melodic themes. The works recorded with bassist Mark Helias and koto player Miya Masaoka are a little looser. Both of these players seem to be there to react to Bloom’s improvisations, and neither finds the opportunity to lead (at least, that’s how it sounds to me). With COVID seemingly in its last phases, I expect that Bloom will return to regular recording and performing and that these compositions will return in larger settings. Perhaps there might be a “Focus 2” recording that records all of the musicians in the same recording space and presents the music within its original concept.

TERRI LYNE CARRINGTON: “NEW STANDARDS, VOLUME 1” (Candid 32012)

With a steady and welcome increase in the number and proficiency of female jazz musicians, Terri Lyne Carrington has completed a long overdue project: a published collection of jazz compositions written by women. That book, “New Standards” (published by Berklee/Hal Leonard) includes 101 pieces (all newly edited and corrected) and it has already proved to be a quick seller among jazz musicians. The companion piece to that book is Carrington’s CD “New Standards, Volume 1” which presents superb new recordings of 11 of the book’s charts. Carrington leads the quintet on the recording—Nicholas Payton (trumpet), Kris Davis (piano), Matthew Stevens (guitar), Linda May Han Oh (bass)—along with a bevy of guest artists. Sara Cassey’s rhythmically complex “Wild Flower” gets the opening spot, with flutist Elena Pinderhughes and guitarist Julian Lage added as soloists. Michael Mayo’s full-voiced baritone vocal is a shock compared to Gretchen Parlato’s original version; however, if these pieces are to be performed by others it makes sense to include them in a different setting than the premiere recording. “Uplifted Heart” was composed by Shamie Royston (part of a musical family in Denver). After a pseudo-rap opening by Shadrack Oppong, Pinderhughes returns as flute soloist, with Ravi Coltrane playing a lean tenor sax solo—with responses from Payton—near the end of the track. Coltrane sticks around for Eliane Elias’ lyrical “Moments”. Dianne Reeves sings with rich emotions, and both Coltrane and Stevens offer fine obbligati, all presented over Oh’s inquisitive bass lines and Carrington’s tempestuous brushes. The introduction of Patricia Perez’ “Continental Cliff” gives Oh a welcome bass solo, and a commanding role within the rhythm section. Milena Casado Fauquet plays a stunning flugelhorn solo, with Davis’ piano following the same exploratory mode. Abbey Lincoln’s iconic “Throw It Away” features Melanie Charles and Somi sharing the vocal duties, with Davis contributing a harmonically-challenging piano solo. Brandee Younger’s funk-driven “Respected Destroyer” utilizes the strong frontline of Pinderhughes, Coltrane, and Payton in ensemble and solo roles. Samara Joy adroitly phrases the short two-note phrases of Carla Bley‘s “Lawns”, gradually filling in the spaces to create a flowing melodic line. Coltrane makes his final appearance on the album with a highly emotional solo. A dual improvisation by Payton and Stevens, and another fine solo by Oh, highlight a compact arrangement of Marta Sanchez’ “Unchanged”, while Anat Cohen’s “Ima” showcases Lage, Davis, and bass clarinetist Veronica Leahy in beautifully understated improvisations. The final track, Marilyn Crispell’s “Rounds” was recorded live at The Red Room at Berklee’s Boston campus. Ambrose Akinmusire replaces Payton, and the interplay between the musicians is noticeably heightened. A triple improvisation for trumpet, piano, and drums is particularly exciting, and considering this electric chemistry, one wonders why Akinmusire wasn’t invited to play on the remainder of the album. Of course, there should be time for that (barring unexpected events): assuming there are more volumes of this set forthcoming, many more fine musicians could present their interpretations of music by the great female jazz composers.

With a steady and welcome increase in the number and proficiency of female jazz musicians, Terri Lyne Carrington has completed a long overdue project: a published collection of jazz compositions written by women. That book, “New Standards” (published by Berklee/Hal Leonard) includes 101 pieces (all newly edited and corrected) and it has already proved to be a quick seller among jazz musicians. The companion piece to that book is Carrington’s CD “New Standards, Volume 1” which presents superb new recordings of 11 of the book’s charts. Carrington leads the quintet on the recording—Nicholas Payton (trumpet), Kris Davis (piano), Matthew Stevens (guitar), Linda May Han Oh (bass)—along with a bevy of guest artists. Sara Cassey’s rhythmically complex “Wild Flower” gets the opening spot, with flutist Elena Pinderhughes and guitarist Julian Lage added as soloists. Michael Mayo’s full-voiced baritone vocal is a shock compared to Gretchen Parlato’s original version; however, if these pieces are to be performed by others it makes sense to include them in a different setting than the premiere recording. “Uplifted Heart” was composed by Shamie Royston (part of a musical family in Denver). After a pseudo-rap opening by Shadrack Oppong, Pinderhughes returns as flute soloist, with Ravi Coltrane playing a lean tenor sax solo—with responses from Payton—near the end of the track. Coltrane sticks around for Eliane Elias’ lyrical “Moments”. Dianne Reeves sings with rich emotions, and both Coltrane and Stevens offer fine obbligati, all presented over Oh’s inquisitive bass lines and Carrington’s tempestuous brushes. The introduction of Patricia Perez’ “Continental Cliff” gives Oh a welcome bass solo, and a commanding role within the rhythm section. Milena Casado Fauquet plays a stunning flugelhorn solo, with Davis’ piano following the same exploratory mode. Abbey Lincoln’s iconic “Throw It Away” features Melanie Charles and Somi sharing the vocal duties, with Davis contributing a harmonically-challenging piano solo. Brandee Younger’s funk-driven “Respected Destroyer” utilizes the strong frontline of Pinderhughes, Coltrane, and Payton in ensemble and solo roles. Samara Joy adroitly phrases the short two-note phrases of Carla Bley‘s “Lawns”, gradually filling in the spaces to create a flowing melodic line. Coltrane makes his final appearance on the album with a highly emotional solo. A dual improvisation by Payton and Stevens, and another fine solo by Oh, highlight a compact arrangement of Marta Sanchez’ “Unchanged”, while Anat Cohen’s “Ima” showcases Lage, Davis, and bass clarinetist Veronica Leahy in beautifully understated improvisations. The final track, Marilyn Crispell’s “Rounds” was recorded live at The Red Room at Berklee’s Boston campus. Ambrose Akinmusire replaces Payton, and the interplay between the musicians is noticeably heightened. A triple improvisation for trumpet, piano, and drums is particularly exciting, and considering this electric chemistry, one wonders why Akinmusire wasn’t invited to play on the remainder of the album. Of course, there should be time for that (barring unexpected events): assuming there are more volumes of this set forthcoming, many more fine musicians could present their interpretations of music by the great female jazz composers.

AL FOSTER: “REFLECTIONS” (Smoke Sessions 2203)

While the label clearly states “Smoke Sessions”, Al Foster’s new CD “Reflections” sounds just like a 1960s Blue Note record. Foster was part of that scene, making his debut recordings as part of Blue Mitchell’s quintet (Chick Corea was another burgeoning talent within that band), and many of the artists Foster idolized—and later worked with—recorded some of their best work for Blue Note. “Reflections” is a tribute album, and the subjects of Foster’s homages represent the top layer of Blue Note’s roster: Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, and Joe Henderson. The loping two-beat feel of the opening track, “T.S. Monk” combines the angular style of Monk Senior with the sly funkiness of Horace Silver. The front line of Nicholas Payton and Chris Potter captures the style of vintage Blue Note, and while each man is playing in an older style, they enrich that sound with spirited improvisations and tight ensemble playing, so that the result sounds historically accurate and not like an anachronism. Potter sails into his solo on Sonny Rollins’ “Pent-Up House” with a clear invocation of the master’s thematic approach and jagged lines. Payton’s solo captures the latter versions of bebop as interpreted by the Young Lions of the 1980s (of which Payton was a member). Foster, who drives the band with uncompromised energy on the first two tracks, plays a stunning accompaniment on toms and cymbals during Potter’s solo on his original, “Open Plans”. Payton then plays glorious improvised melodies with a beautiful fat tone, before pianist Kevin Hays contributes a twisting, oblique solo turn. Potter, bassist Vincente Archer and Foster play Tyner’s “Blues on the Corner” as a trio. Potter stretches the harmony over Archer’s walking lines and Foster’s sparse commentary. In the liner notes, Foster says that the original drummer for this piece, Elvin Jones, was a huge inspiration, but Foster feels that Jones’ style was too personal to copy outright. Foster’s light cymbals and ringing toms combine for a solo that sounds like no one else. “Anastasia” is an intense ballad from Foster’s pen. Potter switches to soprano sax on this track, playing the straight horn with a warm, inviting tone, which is perfectly matched with Payton’s flugelhorn. Payton’s “Six” opens with Rhodes piano with a 1970s effects box attached. It moves into a lean funk feel, and the groove by Archer and Foster sits right in the pocket. Payton’s solo features darting lines reminiscent of Miles Davis’ early funk solos. Potter gets gritty with a darker sound and short motives. Hays’ serpentine lines are enhanced with the keyboard’s tone shifter, and Foster plays a series of tight figures on tenor drum over an ongoing vamp. Joe Henderson’s “Punjab” is one of the great Blue Note themes, and Foster’s group retains the original arrangement. The soloists respect the language of the original band members, moving just slightly beyond so that they can maintain their independent solo voices without losing sight of the original. The horns shine on “Beat”, a Hays ballad with a sophisticated harmonic sequence, and the combination of Hays’ sensitive touch and his understated approach makes the rhythm section’s feature on Herbie Hancock’s “Alone and I” one of the album’s highlights. “Half Nelson” is the oldest tune on the program—recorded on Miles Davis’ first session as a leader—and the relaxed groove here allows the soloists to lay back and blow over a great set of changes. There’s precious little Monk in the closer “Monk’s Bossa” (except for a handful of minor seconds in the melody line and some angular commentary from Hays during the solos). Still, the amiable Foster original does not dim the brilliance of this noteworthy album.

“Reflections” sounds just like a 1960s Blue Note record. Foster was part of that scene, making his debut recordings as part of Blue Mitchell’s quintet (Chick Corea was another burgeoning talent within that band), and many of the artists Foster idolized—and later worked with—recorded some of their best work for Blue Note. “Reflections” is a tribute album, and the subjects of Foster’s homages represent the top layer of Blue Note’s roster: Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, McCoy Tyner, Herbie Hancock, and Joe Henderson. The loping two-beat feel of the opening track, “T.S. Monk” combines the angular style of Monk Senior with the sly funkiness of Horace Silver. The front line of Nicholas Payton and Chris Potter captures the style of vintage Blue Note, and while each man is playing in an older style, they enrich that sound with spirited improvisations and tight ensemble playing, so that the result sounds historically accurate and not like an anachronism. Potter sails into his solo on Sonny Rollins’ “Pent-Up House” with a clear invocation of the master’s thematic approach and jagged lines. Payton’s solo captures the latter versions of bebop as interpreted by the Young Lions of the 1980s (of which Payton was a member). Foster, who drives the band with uncompromised energy on the first two tracks, plays a stunning accompaniment on toms and cymbals during Potter’s solo on his original, “Open Plans”. Payton then plays glorious improvised melodies with a beautiful fat tone, before pianist Kevin Hays contributes a twisting, oblique solo turn. Potter, bassist Vincente Archer and Foster play Tyner’s “Blues on the Corner” as a trio. Potter stretches the harmony over Archer’s walking lines and Foster’s sparse commentary. In the liner notes, Foster says that the original drummer for this piece, Elvin Jones, was a huge inspiration, but Foster feels that Jones’ style was too personal to copy outright. Foster’s light cymbals and ringing toms combine for a solo that sounds like no one else. “Anastasia” is an intense ballad from Foster’s pen. Potter switches to soprano sax on this track, playing the straight horn with a warm, inviting tone, which is perfectly matched with Payton’s flugelhorn. Payton’s “Six” opens with Rhodes piano with a 1970s effects box attached. It moves into a lean funk feel, and the groove by Archer and Foster sits right in the pocket. Payton’s solo features darting lines reminiscent of Miles Davis’ early funk solos. Potter gets gritty with a darker sound and short motives. Hays’ serpentine lines are enhanced with the keyboard’s tone shifter, and Foster plays a series of tight figures on tenor drum over an ongoing vamp. Joe Henderson’s “Punjab” is one of the great Blue Note themes, and Foster’s group retains the original arrangement. The soloists respect the language of the original band members, moving just slightly beyond so that they can maintain their independent solo voices without losing sight of the original. The horns shine on “Beat”, a Hays ballad with a sophisticated harmonic sequence, and the combination of Hays’ sensitive touch and his understated approach makes the rhythm section’s feature on Herbie Hancock’s “Alone and I” one of the album’s highlights. “Half Nelson” is the oldest tune on the program—recorded on Miles Davis’ first session as a leader—and the relaxed groove here allows the soloists to lay back and blow over a great set of changes. There’s precious little Monk in the closer “Monk’s Bossa” (except for a handful of minor seconds in the melody line and some angular commentary from Hays during the solos). Still, the amiable Foster original does not dim the brilliance of this noteworthy album.

TOM HARRELL: “OAK TREE” (High Note 7332)

“Oak Tree” is the latest album of original compositions by Tom Harrell. It is unusual in that Harrell is the only horn on the album, giving him the option of longer solos or more tracks. While he is in extraordinary form, he has apparently gone for the second option, loading 11 new songs into an album that runs just under an hour. Harrell plays with a full clarion tone and flowing bop lines on the opener “Evoorg”, with pianist Luis Perdomo proving as a worthy foil to the leader. The mood turns to light funk on “Fivin’” as Perdomo switches to Rhodes and bassist Ugonna Okegwo and drummer Adam Cruz collaborate on a dancing funk pattern. Harrell’s trumpet skips and jumps over the joyous beat, contrasted by a piano solo tightly aligned with the rhythm, and a bass chorus that enhances the groove. The title track has an intriguing melody based on two related motives and a brief trumpet solo over a background that intimates two-beat and four-beat patterns. The melody of “Tribute” is a Brazilian cameo with a melody reminiscent of Tom Jobim’s “One-Note Samba”, while “Zatoichi” features Harrell in an overdubbed duet with himself over a rhythm section background. The competing trumpet lines get quite heated, and they lead to a collective free improvisation by the rhythm section. In contrast, “Sun Up” sounds like a feel-good reggae song from the 1970s, on which Harrell, Perdomo, and Okegwo keep their solos light and undramatic. Even a shifting time signature can’t add a dark cloud to this original! “Improv” is a bebop line played over a compressed form. Unfortunately, Harrell’s swinging solo is masked by two overdubbed lines of ensemble parts. Cruz creates an exotic background on “Shadows” over which Harrell spins a glorious flugelhorn solo, again accompanied by overdubbed horns (and I must say that the effect becomes rather tiresome by this point). Okegwo’s pulsing bass emphasizes the medium tempo for “Archaeopteryx”, and all of the members of the group contribute well-constructed brief solos over the fine chord sequence. “Robot Etude” opens with a powerful melody in straight eighths before segueing into a quieter (but only slightly less eerie) mood for solos. Perdomo’s solo hovers around a limited set of pitches, which is followed by Okegwo’s declamatory bass. Harrell’s poetic flugelhorn statement sounds like a deep dive into Miles Davis’ “Solea” from “Sketches of Spain”. The attractive “Love Tide” closes the program with a pleasant collection of solos. Harrell has had severe health problems in the two years since he recorded this album. He’s back in the studio as I write this notice, so we can rejoice that he continues to write and perform his extraordinary music.

“Oak Tree” is the latest album of original compositions by Tom Harrell. It is unusual in that Harrell is the only horn on the album, giving him the option of longer solos or more tracks. While he is in extraordinary form, he has apparently gone for the second option, loading 11 new songs into an album that runs just under an hour. Harrell plays with a full clarion tone and flowing bop lines on the opener “Evoorg”, with pianist Luis Perdomo proving as a worthy foil to the leader. The mood turns to light funk on “Fivin’” as Perdomo switches to Rhodes and bassist Ugonna Okegwo and drummer Adam Cruz collaborate on a dancing funk pattern. Harrell’s trumpet skips and jumps over the joyous beat, contrasted by a piano solo tightly aligned with the rhythm, and a bass chorus that enhances the groove. The title track has an intriguing melody based on two related motives and a brief trumpet solo over a background that intimates two-beat and four-beat patterns. The melody of “Tribute” is a Brazilian cameo with a melody reminiscent of Tom Jobim’s “One-Note Samba”, while “Zatoichi” features Harrell in an overdubbed duet with himself over a rhythm section background. The competing trumpet lines get quite heated, and they lead to a collective free improvisation by the rhythm section. In contrast, “Sun Up” sounds like a feel-good reggae song from the 1970s, on which Harrell, Perdomo, and Okegwo keep their solos light and undramatic. Even a shifting time signature can’t add a dark cloud to this original! “Improv” is a bebop line played over a compressed form. Unfortunately, Harrell’s swinging solo is masked by two overdubbed lines of ensemble parts. Cruz creates an exotic background on “Shadows” over which Harrell spins a glorious flugelhorn solo, again accompanied by overdubbed horns (and I must say that the effect becomes rather tiresome by this point). Okegwo’s pulsing bass emphasizes the medium tempo for “Archaeopteryx”, and all of the members of the group contribute well-constructed brief solos over the fine chord sequence. “Robot Etude” opens with a powerful melody in straight eighths before segueing into a quieter (but only slightly less eerie) mood for solos. Perdomo’s solo hovers around a limited set of pitches, which is followed by Okegwo’s declamatory bass. Harrell’s poetic flugelhorn statement sounds like a deep dive into Miles Davis’ “Solea” from “Sketches of Spain”. The attractive “Love Tide” closes the program with a pleasant collection of solos. Harrell has had severe health problems in the two years since he recorded this album. He’s back in the studio as I write this notice, so we can rejoice that he continues to write and perform his extraordinary music.

ENRICO RAVA & FRED HERSCH: “THE SONG IS YOU” (ECM 2746)

The Italian flugelhornist Enrico Rava and American pianist Fred Hersch have both been on the jazz scene long enough to be considered elder statesmen. While each man has amassed impressive lists of collaborators, their new CD, “The Song is You” represents the first time they have recorded together (In a related surprise, this is Hersch’s first recording on the ECM label). Both men are fond of the duo format, and from the recorded evidence, it sounds like they found common ground rather quickly. As in any great jazz duet, there is a great sense of freedom and interplay, with elastic tempos and subtle changes in the leader and follower roles. The opening track, Tom Jobim’s “Retrato em Blanco e Preto” (aka “Zingaro”) shows the pair at their most lyrical, caressing the lovely melody while exploring its emotional depths. Next is a free piece aptly titled “Improvisation”. I doubt that there was much discussion prior to starting the tape, since the music shifts in focus and direction. However, because Rava and Hersch bring deep musicality to every piece they play, there is still a sense of logic to what they play here, even if there wasn’t anything planned beforehand. “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” finds Rava blowing long flowing lines over Hersch’s lightly skipping accompaniment. Hersch maintains the style through his solo, which playfully jumps to both ends of the keyboard. Rava joins in the fun at the end, as he shortens and tightens his phrases. The title track opens with an atonal collective improvisation. In the midst of the passage, Rava finds the passage to Jerome Kern’s melody, and Hersch picks up the signal and establishes the key. From that point, the tune is lavishly ornamented, but clearly identifiable at all times. And then, as quickly as they found the entrance, they leave, returning to the freestyle of the opening. Hersch’s delicate “A Child’s Song” has been a regular part of his repertoire for over four decades (a version appears on “As One” discussed in the Jane Ira Bloom review above). In this version, Rava improvises over a muted single-note accompaniment. During the course of the solo, Hersch gradually opens up and closes down the harmony, eventually letting Rava play without him. Hersch opens the harmony again for his solo, which begins with a dramatic passage in the left hand. He builds the solo gradually before easing back into the song’s original vamp. Rava’s original composition “The Trial” is presented as a two-minute cameo, starting with Hersch alone on a winding single-line improvisation and Rava joining in for spontaneous counterpoint. It all comes back to Rava’s melody, but it’s hard to pinpoint where they make the change from extemporaneous to written music. The album’s final two pieces were written by Thelonious Monk. After the theme, “Misterioso” features a Hersch solo which starts out free (but includes development of the theme) before slowly moving back to the blues. At first, Rava sounds like he wants to take it back to free, but his phrases fit within the blues form, and Hersch leads the way further in. However, the rope pull between free and tonal keeps moving back and forth, and the two musicians discover ways to balance the opposing styles. I’m not sure why Rava didn’t play on “Round Midnight”, but it is always a treat to hear Hersch play solo Monk. This version is primarily dark and tense with the greatest relief coming in the final bell-like tones of the coda.

have both been on the jazz scene long enough to be considered elder statesmen. While each man has amassed impressive lists of collaborators, their new CD, “The Song is You” represents the first time they have recorded together (In a related surprise, this is Hersch’s first recording on the ECM label). Both men are fond of the duo format, and from the recorded evidence, it sounds like they found common ground rather quickly. As in any great jazz duet, there is a great sense of freedom and interplay, with elastic tempos and subtle changes in the leader and follower roles. The opening track, Tom Jobim’s “Retrato em Blanco e Preto” (aka “Zingaro”) shows the pair at their most lyrical, caressing the lovely melody while exploring its emotional depths. Next is a free piece aptly titled “Improvisation”. I doubt that there was much discussion prior to starting the tape, since the music shifts in focus and direction. However, because Rava and Hersch bring deep musicality to every piece they play, there is still a sense of logic to what they play here, even if there wasn’t anything planned beforehand. “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” finds Rava blowing long flowing lines over Hersch’s lightly skipping accompaniment. Hersch maintains the style through his solo, which playfully jumps to both ends of the keyboard. Rava joins in the fun at the end, as he shortens and tightens his phrases. The title track opens with an atonal collective improvisation. In the midst of the passage, Rava finds the passage to Jerome Kern’s melody, and Hersch picks up the signal and establishes the key. From that point, the tune is lavishly ornamented, but clearly identifiable at all times. And then, as quickly as they found the entrance, they leave, returning to the freestyle of the opening. Hersch’s delicate “A Child’s Song” has been a regular part of his repertoire for over four decades (a version appears on “As One” discussed in the Jane Ira Bloom review above). In this version, Rava improvises over a muted single-note accompaniment. During the course of the solo, Hersch gradually opens up and closes down the harmony, eventually letting Rava play without him. Hersch opens the harmony again for his solo, which begins with a dramatic passage in the left hand. He builds the solo gradually before easing back into the song’s original vamp. Rava’s original composition “The Trial” is presented as a two-minute cameo, starting with Hersch alone on a winding single-line improvisation and Rava joining in for spontaneous counterpoint. It all comes back to Rava’s melody, but it’s hard to pinpoint where they make the change from extemporaneous to written music. The album’s final two pieces were written by Thelonious Monk. After the theme, “Misterioso” features a Hersch solo which starts out free (but includes development of the theme) before slowly moving back to the blues. At first, Rava sounds like he wants to take it back to free, but his phrases fit within the blues form, and Hersch leads the way further in. However, the rope pull between free and tonal keeps moving back and forth, and the two musicians discover ways to balance the opposing styles. I’m not sure why Rava didn’t play on “Round Midnight”, but it is always a treat to hear Hersch play solo Monk. This version is primarily dark and tense with the greatest relief coming in the final bell-like tones of the coda.

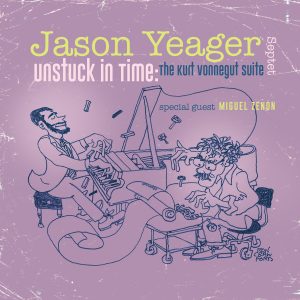

JASON YEAGER: “UNSTUCK IN TIME: THE KURT VONNEGUT SUITE” (Sunnyside 1672)

As a freshman in college, I once wrote a very odd research paper that claimed that Kurt Vonnegut had been influenced by Thelonious Monk. I wasn’t a very good writer in those days, and I recall that the paper broke all types of structural rules. After I learned the errors of my ways, I discarded the only copy of the paper as useless juvenilia. However, when I met Vonnegut a few years later, he confirmed that he was a jazz fan and enjoyed Monk’s music. He didn’t say anything about influence though… Pianist/composer Jason Yeager’s CD “Unstuck in Time” was released on Vonnegut’s centenary, and it successfully—certainly more than I—captures the quirky, yet thought-provoking style of the master novelist. In his liner notes, Yeager invites listeners to “become unstuck in time” like Billy Pilgrim, and play the tracks in any order they wish. The assigned track sequence will work fine for our purposes, but I will doubtlessly try random programming when this disc returns to my player. “Now It’s the Women’s Turn”, inspired by the surprise ending of Vonnegut’s “Bluebeard”, is a loose tango with Lucas Pino’s clarinet solo stretching tonal boundaries over Jay Sawyer’s propulsive drums. Yeager plays a bare-bones style here, using single lines and spare harmony in the first half of his solo before strengthening the lines with octave doubles. Pino, Yeager, and trumpeter Alphonso Horne play a brief collective improvisation before the track ends. Guest alto saxophonist Miguel Zenon begins the portrait of “Bokonon” (the religious leader from “Cat’s Cradle”) with a playful solo that toys with traditional intonation. After the buoyant Caribbean-styled theme, Zenon returns for a burning solo that builds intensity with every bar. Yeager’s high-register solo rides over the ensemble backgrounds. “Ballad for Old Salo” delves into Vonnegut’s unique version of science fiction, with the subject being a Tralfamadorian who wants to befriend a human, but is rebuffed instead. Pino’s clarinet and Mike Fahie’s trombone combine with Yuhan Su’s vibes and Horne’s flugel to create a lonely atmosphere, with the dual improvisation of vibes and piano representing Salo’s wish. “Kilgore’s Creed” opens with Vonnegut/Kilgore Trout’s words chanted by the band. The uneven 7/4 time signature sounds like an allegory for the “timequake” where we enter into cyclical time and repeat our old mistakes. “Unk’s Fate” from “Sirens of Titan” uses a march rhythm to portray an invading army of Martians. Zenon’s soulful alto and Yeager’s bright piano bring a sense of humanity to this grim scene. “So it Goes” was the phrase said whenever someone died in “Slaughterhouse Five”. Yeager uses a variety of spoken voices over a free jazz background for this brief movement. The same motive, played on Pino’s bass clarinet, leads the way to “Blues for Billy Pilgrim”, a slow and quizzical work with an outstanding solo by Horne. “Nancy’s Revenge” refers to a never-written (and presumably more feminist-friendly) sequel to “Welcome to the Monkey House”. On this and three other tracks, Patrick Laslie replaces Pino, and Riley Mulherkar replaces Horne. Both play superb solos and are fine substitutes within the ensemble. “Rudy’s Waltz” for the 12-year-old aka “Deadeye Dick” features the leader’s piano, along with a brief solo by bassist Danny Weller. “Blue Fairy Godmother” is a pseudonym for a male intelligence officer in “Mother Night”. Fahie, Laslie, and Mulharker play up the humor of the subject. The album’s track sequence ends with “Tralfamadorian Rhapsody”, a funk piece that Yeager imagines as the spaceman’s anthem. Well, it’s a long way from ‘The Star-Spangled Banner”! This album serves as an excellent tribute to Kurt Vonnegut. I think I’m going to dig out those old paperbacks…

As a freshman in college, I once wrote a very odd research paper that claimed that Kurt Vonnegut had been influenced by Thelonious Monk. I wasn’t a very good writer in those days, and I recall that the paper broke all types of structural rules. After I learned the errors of my ways, I discarded the only copy of the paper as useless juvenilia. However, when I met Vonnegut a few years later, he confirmed that he was a jazz fan and enjoyed Monk’s music. He didn’t say anything about influence though… Pianist/composer Jason Yeager’s CD “Unstuck in Time” was released on Vonnegut’s centenary, and it successfully—certainly more than I—captures the quirky, yet thought-provoking style of the master novelist. In his liner notes, Yeager invites listeners to “become unstuck in time” like Billy Pilgrim, and play the tracks in any order they wish. The assigned track sequence will work fine for our purposes, but I will doubtlessly try random programming when this disc returns to my player. “Now It’s the Women’s Turn”, inspired by the surprise ending of Vonnegut’s “Bluebeard”, is a loose tango with Lucas Pino’s clarinet solo stretching tonal boundaries over Jay Sawyer’s propulsive drums. Yeager plays a bare-bones style here, using single lines and spare harmony in the first half of his solo before strengthening the lines with octave doubles. Pino, Yeager, and trumpeter Alphonso Horne play a brief collective improvisation before the track ends. Guest alto saxophonist Miguel Zenon begins the portrait of “Bokonon” (the religious leader from “Cat’s Cradle”) with a playful solo that toys with traditional intonation. After the buoyant Caribbean-styled theme, Zenon returns for a burning solo that builds intensity with every bar. Yeager’s high-register solo rides over the ensemble backgrounds. “Ballad for Old Salo” delves into Vonnegut’s unique version of science fiction, with the subject being a Tralfamadorian who wants to befriend a human, but is rebuffed instead. Pino’s clarinet and Mike Fahie’s trombone combine with Yuhan Su’s vibes and Horne’s flugel to create a lonely atmosphere, with the dual improvisation of vibes and piano representing Salo’s wish. “Kilgore’s Creed” opens with Vonnegut/Kilgore Trout’s words chanted by the band. The uneven 7/4 time signature sounds like an allegory for the “timequake” where we enter into cyclical time and repeat our old mistakes. “Unk’s Fate” from “Sirens of Titan” uses a march rhythm to portray an invading army of Martians. Zenon’s soulful alto and Yeager’s bright piano bring a sense of humanity to this grim scene. “So it Goes” was the phrase said whenever someone died in “Slaughterhouse Five”. Yeager uses a variety of spoken voices over a free jazz background for this brief movement. The same motive, played on Pino’s bass clarinet, leads the way to “Blues for Billy Pilgrim”, a slow and quizzical work with an outstanding solo by Horne. “Nancy’s Revenge” refers to a never-written (and presumably more feminist-friendly) sequel to “Welcome to the Monkey House”. On this and three other tracks, Patrick Laslie replaces Pino, and Riley Mulherkar replaces Horne. Both play superb solos and are fine substitutes within the ensemble. “Rudy’s Waltz” for the 12-year-old aka “Deadeye Dick” features the leader’s piano, along with a brief solo by bassist Danny Weller. “Blue Fairy Godmother” is a pseudonym for a male intelligence officer in “Mother Night”. Fahie, Laslie, and Mulharker play up the humor of the subject. The album’s track sequence ends with “Tralfamadorian Rhapsody”, a funk piece that Yeager imagines as the spaceman’s anthem. Well, it’s a long way from ‘The Star-Spangled Banner”! This album serves as an excellent tribute to Kurt Vonnegut. I think I’m going to dig out those old paperbacks…