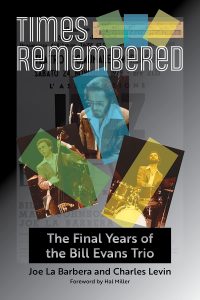

One of the first lessons we learn—either as a jazz fan or fledgling musician—is that the jazz community is a friendly and supportive group. There is a long-held convention that the present jazz audience must build and develop young musicians and fans to ensure the music’s survival and development. With a few notable exceptions, jazz musicians seem particularly eager to guide the paths of young musicians in ways ranging from advice, lessons, and recommended recordings through playing opportunities including sitting in on club dates and the ultimate reward, an ongoing position as a member of a master’s working band. At that rarefied position, the young musician makes several discoveries: first, that they are indeed good enough to play at this level (and will doubtlessly be challenged to maintain that level of excellence) and second, that the master musician is, at the core, another human being, with a unique collection of habits, values, and problems. When drummer Joe La Barbera was hired as the newest member of the Bill Evans trio in January 1979, he knew that Evans had a long-standing addiction to drugs. Evans died of his addiction just 19 months later, while La Barbera was still with the band. The triumphs and tribulations of that final edition of the Evans trio (with Marc Johnson on bass) are the subjects of La Barbera’s frank and touching memoir, “Times Remembered: The Final Years of the Bill Evans Trio” (University of North Texas Press).

Upon entering the Evans trio, La Barbera discovered that there were no drum charts to follow. Over the years, Evans had devised his own approaches to his repertoire, and those arrangements carried through changes in the trio’s personnel. Thus, Evans expected that his new musicians would know the basic song frameworks from Evans’ earlier recordings, and would find their own way to mold their own styles into the Evans trio fabric. The absence of written music also allowed the bassist and drummer to create their own parts on the spot, making their contributions unique from the outset. Just weeks into the new group’s existence, they filmed two one-hour sets for Iowa Public Television for the series “Jazz at the Maintenance Shop”, which showed that the group had already developed its own approach to the leader’s longtime goal of collective trio improvisation. On the videos, complete here and here, Evans gripes about the piano and the sound, but his inspired playing reflects his happiness with this new group. Outside events interfered with the group’s progress in mid-April as Evans abruptly canceled a gig in Calgary due to an unacceptable piano, and a few days later at Washington DC’s Blues Alley, when Evans stopped playing in the midst of a set after hearing of the suicide of his brother Harry.

Harry’s death was a crushing blow to his famous brother. While La Barbera does not state it outright, it seems obvious that Evans’ drug intake increased around this time as he found fewer reasons to continue living. In a 1966 film interview with Harry, Evans said that turning on his creativity was like flicking a light switch. This mindset allowed Evans to play inspired performances even as his general health deteriorated. Evans actually encouraged La Barbera to develop the same technique at the time, but the drummer admits only being partially successful at implementing the concept. Evans’ cavalier attitude towards life is captured in stunning detail as La Barbera tells of a dinner break before a concert at Evans’ alma mater, Southeastern Louisiana University. The trio was dining at an off-campus restaurant when a bullet broke an outside window and lodged in the wall just above the musicians. La Barbera was visibly shaken by the experience, but Evans wisecracked to him, “What’s wrong? Are you afraid of dying?” With a wife and newborn child, La Barbera had plenty to live for, even if his employer did not. A few months later, Evans was involved in a single-car accident while traveling from his apartment in Fort Lee, NJ to Carnegie Hall. He arrived at the hall 15 minutes before the performance with his left arm in a sling, stitches in his eyebrow, and bandages on his nose and glasses. While his fellow musicians were shocked at his condition, Evans was nonchalant, finding a cup of coffee backstage before flicking the switch and starting his performance.

This edition of the Evans trio only made a single album in the studio—the magnificent “We Will Meet Again”, featuring Tom Harrell (trumpet) and Larry Schneider (saxes) and dedicated to Harry’s memory—but their string of extraordinary live performances survives in a series of videos and sound recordings. La Barbera only notes one instance of Evans being physically unable to play, having “a cognitive breakdown”, where Evans completely lost track of the key and song form in the midst of a live improvisation. This incident occurred in Italy during the summer of 1980, but Evans recovered quickly and performed most of his scheduled concerts, even as his body continued to deteriorate. After two weeks of marathon recording at the Village Vanguard and Keystone Korner (resulting in an astounding 22 CDs worth of sublime music), the trio was scheduled for a week-long engagement at the New York club, Fat Tuesday’s. Evans played two nights of the gig before falling ill on September 10. Five days later, La Barbera was driving Evans to his doctor’s office when the pianist started coughing up blood. Evans told La Barbera to take him to Mt. Sinai Hospital, and the panicked drummer sped the wrong way down two one-way streets before arriving at the emergency room. Evans died there within an hour.

Joe La Barbera has dug deep into his memory bank for this memoir. He has not sensationalized the details, and while we can understand the pain and frustration of watching his employer, friend, and mentor gradually losing his will to live, La Barbera’s narrative makes us believe that he still holds a great deal of love and admiration for Bill Evans. La Barbera moved on with a long tenure as Tony Bennett’s drummer, and a teaching career at Cal Arts, but there is little doubt that his 19 months as a member of the final Bill Evans trio was a defining moment in his life. The music this Evans trio created is as remarkable as Evans’ classic sessions with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian. Let their recorded legacy shine as brightly as their predecessors despite—or even because of—their dramatic backstories.