Highly anticipated and severely delayed, Mosaic’s new collection “The Complete Louis Armstrong Columbia & RCA Victor Studio Sessions, 1946-1966” has finally arrived, showcasing three remarkable albums, “Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy”, “Satch Plays Fats” [Waller] and “The Real Ambassadors”, along with singles and collaborations. The music is thematically distributed across the 7 discs, with the singles and collaborations appearing on discs 1 and 2, “Handy” spread over discs 3 and 4, with “Fats” and “Ambassadors” splitting discs 5-7. The accompanying booklet is massive, with much of its 44 pages holding Ricky Riccardi’s exhaustive 30,000-word essay and an impressively detailed discography, both of which guide us through the creation and editing of each performance (The latter feature is particularly helpful for the sessions originally produced by George Avakian, which will be fully discussed below).

Ricky Riccardi’s exhaustive 30,000-word essay and an impressively detailed discography, both of which guide us through the creation and editing of each performance (The latter feature is particularly helpful for the sessions originally produced by George Avakian, which will be fully discussed below).

From the very beginning of disc 1, it is readily apparent that Armstrong is in top form, both as a trumpeter and singer, and that the sound quality of the set exceeds Mosaic’s usual high standards. The opening session is the 1946 Esquire All-Star Band. Duke Ellington verbally introduces “Long Long Journey” and then Armstrong takes over, with gorgeous instrumental and vocal lines. There is no audible surface noise, nor any distortion to shift our attention from the music—and that remains true throughout most of the set. Armstrong’s big band appears on the following session, and while the arrangements seem a little too modern for Armstrong, both the leader and the band perform the charts with considerable enthusiasm. RCA was clearly looking for hit records with Armstrong, but they didn’t supply inspiring songs for him to record. What did inspire Armstrong was playing with a small group. After he was signed to play a leading role in the film “New Orleans”, Armstrong gathered the band who would share the screen with him for a session for Charles Delaunay’s Swing label. Delaunay was unable to attend the session in person, and he made the unfortunate decision to ask Leonard Feather to supervise. Feather, a born meddler, replaced two members of the band, and apparently limited the group’s  improvised counterpoint. Feather also brought two of his own compositions to the date, and replaced Charlie Beal at the piano for those tracks (Feather claimed that Zutty Singleton encouraged him to sit in). Delaunay was furious at Feather’s inappropriate actions, and it was nearly 40 years before the two critics mended fences. At the following session—with Feather notably absent—Armstrong recorded four songs from the score to “New Orleans”, two with his big band, and the other two with the reconstituted combo from the movie. There was time for the small group to play another tune, so Armstrong called “Mahogany Hall Stomp”, which was certainly a highlight of the session. After another session with the big band, we skip ahead three months to June 1947, with Armstrong leading the first edition of his All-Stars, the small combo he would front for the rest of his life. Happily, Jack Teagarden is present on this session, and the two soulmates collaborate on a dynamic “Jack-Armstrong Blues”, and a good—if rushed—performance of “Rockin’ Chair”. A reduced big band arrangement accompanies Armstrong’s debut recording of “Someday You’ll Be Sorry”, and the disc ends with another dull Feather opus, “Fifty-Fifty Blues.”

improvised counterpoint. Feather also brought two of his own compositions to the date, and replaced Charlie Beal at the piano for those tracks (Feather claimed that Zutty Singleton encouraged him to sit in). Delaunay was furious at Feather’s inappropriate actions, and it was nearly 40 years before the two critics mended fences. At the following session—with Feather notably absent—Armstrong recorded four songs from the score to “New Orleans”, two with his big band, and the other two with the reconstituted combo from the movie. There was time for the small group to play another tune, so Armstrong called “Mahogany Hall Stomp”, which was certainly a highlight of the session. After another session with the big band, we skip ahead three months to June 1947, with Armstrong leading the first edition of his All-Stars, the small combo he would front for the rest of his life. Happily, Jack Teagarden is present on this session, and the two soulmates collaborate on a dynamic “Jack-Armstrong Blues”, and a good—if rushed—performance of “Rockin’ Chair”. A reduced big band arrangement accompanies Armstrong’s debut recording of “Someday You’ll Be Sorry”, and the disc ends with another dull Feather opus, “Fifty-Fifty Blues.”

Disc 2 starts off well enough with another All-Stars date for Victor, featuring two more exquisite Armstrong/Teagarden duets on “A Song Was Born” and “Please Stop Playing Those Blues, Boy”. The energy level drops considerably on the session’s two remaining tracks, “Before Long” (composed by the All-Stars’ drummer, Sid Catlett) and “Lovely Weather We’re Having” (written by pianist Joe Bushkin). We then skip ahead to 1954, and the last session for Columbia’s W.C. Handy album. The track was Trummy Young’s feature on “’Tain’t What You Do”, which Armstrong and Avakian term an “audition”. Another forward jump takes to 1955 and a special single session for Columbia which yielded another “Back O’Town” and three different versions of “Mack the Knife” (We’ll return to these songs momentarily). The next three items are ephemeral, but oddly enlightening. A 1956 single session for RCA includes two  completely forgettable songs from a television play. The 1959 “Music to Shave By” featured Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Rosemary Clooney and the Hi-Lo’s hawking an electronic razor. It was issued as a flexible record inside Look magazine, and it must be heard to be believed. Next, comes an uninspired 1966 Columbia single of “Canal Street Blues” and “Cabaret”. If the fatigue of Armstrong and his band is not immediately obvious, just wait until the track changes after the end of “Cabaret”, when we skip backwards 12 years to catch the alternate take of Trummy’s “’Tain’t What You Do”. At the outset of the track, Armstrong is playing a few notes on his trumpet just to keep the horn and his lips warm. In and of itself it’s nothing special, but this innocent noodling has more passion than anything on the 1966 date. After a little good-natured ribbing between Armstrong, Young and Avakian, they launch into a take which is almost more energetic than the “master”. The rest of disc 2 is a fascinating look at the All-Stars at work in the studio. It is the “Back O’ Town”/“Mack the Knife” session, and after a 6-minute rehearsal take on the blues, the band turns to the Kurt Weill theme. Faced with an arrangement filled with bizarre modulations, the group pares down the chart. Mosaic includes about 20 minutes of rehearsal takes and alternates, allowing us to hear how the final All-Stars version was assembled. Weill’s widow, Lotte Lenya, who was playing Polly Peachum in a Broadway production of “The Three Penny Opera” at the time, came to the studio on Avakian’s invite. The duet of Lenya and Armstrong did not come off too well, due to Lenya’s throbbing vibrato

completely forgettable songs from a television play. The 1959 “Music to Shave By” featured Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Rosemary Clooney and the Hi-Lo’s hawking an electronic razor. It was issued as a flexible record inside Look magazine, and it must be heard to be believed. Next, comes an uninspired 1966 Columbia single of “Canal Street Blues” and “Cabaret”. If the fatigue of Armstrong and his band is not immediately obvious, just wait until the track changes after the end of “Cabaret”, when we skip backwards 12 years to catch the alternate take of Trummy’s “’Tain’t What You Do”. At the outset of the track, Armstrong is playing a few notes on his trumpet just to keep the horn and his lips warm. In and of itself it’s nothing special, but this innocent noodling has more passion than anything on the 1966 date. After a little good-natured ribbing between Armstrong, Young and Avakian, they launch into a take which is almost more energetic than the “master”. The rest of disc 2 is a fascinating look at the All-Stars at work in the studio. It is the “Back O’ Town”/“Mack the Knife” session, and after a 6-minute rehearsal take on the blues, the band turns to the Kurt Weill theme. Faced with an arrangement filled with bizarre modulations, the group pares down the chart. Mosaic includes about 20 minutes of rehearsal takes and alternates, allowing us to hear how the final All-Stars version was assembled. Weill’s widow, Lotte Lenya, who was playing Polly Peachum in a Broadway production of “The Three Penny Opera” at the time, came to the studio on Avakian’s invite. The duet of Lenya and Armstrong did not come off too well, due to Lenya’s throbbing vibrato  and lack of swing. Armstrong coached Lenya gently, and eventually she nailed down a troublesome spot in the arrangement. However, the duet recording remained in the vault until the CD era. After all of that work (and the All-Stars just two days away from a month-long European tour) Avakian asked for an instrumental version of “Mack”, just in case radio stations balked at the violent lyrics (It should be remembered that Armstrong’s version was the first American pop recording of the song with English lyrics). The instrumental—with even less energy than the 1966 “Cabaret” session—remained unissued until 1982.

and lack of swing. Armstrong coached Lenya gently, and eventually she nailed down a troublesome spot in the arrangement. However, the duet recording remained in the vault until the CD era. After all of that work (and the All-Stars just two days away from a month-long European tour) Avakian asked for an instrumental version of “Mack”, just in case radio stations balked at the violent lyrics (It should be remembered that Armstrong’s version was the first American pop recording of the song with English lyrics). The instrumental—with even less energy than the 1966 “Cabaret” session—remained unissued until 1982.

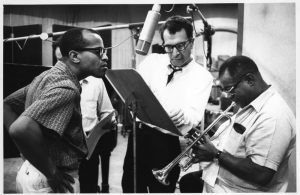

Like a film editor, George Avakian created master takes by freely assembling portions of all available takes. Riccardi notes that there were so many splices in Armstrong’s vocal chorus on “Mack the Knife” that the assembled Mosaic crew could not count them all! Apparently, the All-Stars’ recording was available intact in digital form, so that Mosaic could simply copy the existing cut rather than recreating it from scratch. However, in the cases of the Avakian-produced albums, “Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy” and “Satch Plays Fats”, the unsuitable condition of the master tapes made a total reconstruction of Avakian’s edits an absolute necessity. Adding to the general puzzle were the 1980s reissues of these albums, produced by Michael Brooks. Because the master tapes were missing at that time, Brooks was forced to create new versions of these recordings using alternate takes. The production team of Riccardi, Scott Wenzel, David Ostwald and Richie Noorigan, along with engineers Matt Cavaluzzo and Andreas Meyer, assisted by restoration/mastering engineers Noelle Byer, Nancy Conforti and Jenn Nulsen, went through these recordings with meticulous care, successfully locating and recreating every one of Avakian’s edits through a combination of studio reels and commercial discs. The splices are virtually inaudible, making the music flow just as Avakian intended. Most of the Brooks versions are included here as well, but usually as complete alternate takes, rather than the edited versions. Riccardi had Avakian’s original session notes to work from, courtesy of jazz historian Chris Albertson, but in a sad irony, Avakian, Albertson and Brooks all died while this set was in planning and production. Riccardi explains the editing puzzles in the booklet notes, but it’s much more fun to watch his videos here, here and here. (One of the videos also tells of the handful of previously issued items not included in the Mosaic set. Best suggestion is to double-check the Mosaic against the earlier discs, and decide if you need the scraps that are left.)

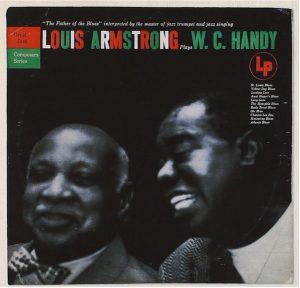

By the time of Armstrong’s 1947 recordings of “A Song Was Born” and “Please Stop Playing Those Blues, Boy”, both Armstrong and his manager Joe Glaser decided to have the trumpeter change labels again. Decca had been a good home for Armstrong, and so—after the 1948 recording ban—he signed a five-year contract with them. When that contract ran out in 1954, Avakian was eager to have his favorite jazz icon on the Columbia roster, so he threw a double-barreled strategy at Armstrong and Glaser: royalties paid on the classic Armstrong recordings Avakian was reissuing on Columbia, and a magnificent idea for a concept album: “Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy”. The extra income appealed to Glaser, and Armstrong jumped at the chance to do the Handy album, offering to create and rehearse arrangements while on tour. The album was a golden opportunity to celebrate Handy, who was blind and in poor health. Armstrong was easily the most-celebrated musician in jazz, and the one person who could bring out the inner qualities of Handy’s music. Armstrong and Avakian both seemed fairly sure that the Handy album could lead to a long-term Columbia contract.

on the Columbia roster, so he threw a double-barreled strategy at Armstrong and Glaser: royalties paid on the classic Armstrong recordings Avakian was reissuing on Columbia, and a magnificent idea for a concept album: “Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy”. The extra income appealed to Glaser, and Armstrong jumped at the chance to do the Handy album, offering to create and rehearse arrangements while on tour. The album was a golden opportunity to celebrate Handy, who was blind and in poor health. Armstrong was easily the most-celebrated musician in jazz, and the one person who could bring out the inner qualities of Handy’s music. Armstrong and Avakian both seemed fairly sure that the Handy album could lead to a long-term Columbia contract.

Most of the 1954 All-Stars—Young, Barney Bigard, Billy Kyle, Arvell Shaw and Velma Middleton —had been with Armstrong for several years. The set lists stayed the same for most of Armstrong’s live appearances, and for the most part, the band members played set solos. The Handy repertoire offered a welcome release from the routine by allowing the  All-Stars to play music that was, at once, new and familiar. They were free to improvise, and to try out fresh ideas. Kyle sketched out settings of the tunes, never forgetting that he was creating an album. Thus, he deliberately added variety to the charts, varying keys, tempos and approaches, so that the resulting LP—including 8 of 11 songs with the word “blues” in the title—would retain interest throughout its running time. To boost the band’s excitement to a higher level, Armstrong hired a new drummer for the All-Stars, Chicago veteran Barrett Deems. Deems was far from subtle, but he could spark a band’s inspiration with a powerful backbeat or a swinging cymbal pattern. The Handy recording was recorded in the Windy City, which allowed Deems to debut on his home turf. All of these elements combined, as the band re-discovered the finely-crafted chemistry between its members, and its innate musicianship.

All-Stars to play music that was, at once, new and familiar. They were free to improvise, and to try out fresh ideas. Kyle sketched out settings of the tunes, never forgetting that he was creating an album. Thus, he deliberately added variety to the charts, varying keys, tempos and approaches, so that the resulting LP—including 8 of 11 songs with the word “blues” in the title—would retain interest throughout its running time. To boost the band’s excitement to a higher level, Armstrong hired a new drummer for the All-Stars, Chicago veteran Barrett Deems. Deems was far from subtle, but he could spark a band’s inspiration with a powerful backbeat or a swinging cymbal pattern. The Handy recording was recorded in the Windy City, which allowed Deems to debut on his home turf. All of these elements combined, as the band re-discovered the finely-crafted chemistry between its members, and its innate musicianship.

Once the All-Stars were in the studio, Avakian let the musicians develop and polish the arrangements. There was no sense of panic when he realized that the album’s opening track, “St. Louis Blues,” was nearly nine minutes long—even though a cut would be necessary to release the cut on a 45rpm EP. The arrangement had an organic flow, and it built steadily through its extended duration. After the first take, Armstrong and Middleton started looking for alternative lyrics, as they were afraid that the words they had just recorded might be offensive. One of those stanzas is indeed troublesome—certainly to modern ears—but Avakian waved off the problem fairly quickly. When Avakian made suggestions, they came from a listener’s perspective, such as proposing a longer ride-out section to an arrangement, adding an ad hoc chorus to emphasize the title phrase of “Long Gone”, or eliminating a voice to clarify an important lyric. I’m not sure if the entire band knew of Avakian’s creative editing techniques (certainly Armstrong did) but regardless, the All-Stars produced enough musical gold in the 3 Handy recording sessions for Avakian to assemble a masterpiece.

The individual highlights of the Handy LP have been noted by many: the majestic version of “St. Louis Blues” with outstanding solos by Bigard, Young, Middleton and Armstrong; Young’s two raucous solos on “Long Gone”; Armstrong’s triumphant high E-flats in the final chorus of “Chantez Le Bas”; the soulful ride-out on “Yellow Dog Blues”, the light-hearted vocals of Armstrong, Middleton and the chorus on “Long Gone”, and Armstrong’s astonishing overdubbed trumpet and vocal obbligatos on “Atlanta Blues”. The Mosaic set adds to the treasure with 100 minutes of alternate takes, warm-ups, rehearsals and studio chatter (About 20 minutes of this material was issued on the 1997 Columbia CD of this album; virtually all of those takes are on the Mosaic, save for Avakian’s interview with Handy). Riccardi pinpoints Avakian’s major edits in his notes, but it is still a shock while listening to the original unedited takes when the music suddenly moves from the familiar to the new! More instructive are the long rehearsal sequences: the arrangements coalesce in front of our ears; ideas are suggested and tried out, decisions are made and implemented on the spot, mistakes are made and corrected, and—as we can hear now—some superb music was left on the cutting room floor. To be clear, Mosaic did not include every scrap of unissued tape from these sessions, but I have enough faith in the musical sensibilities of the Mosaic production team to believe that we are hearing all of the worthy material from these sessions.

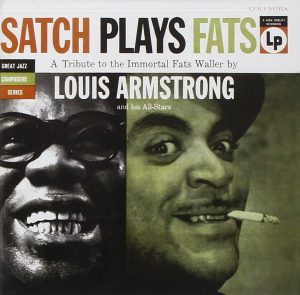

The follow-up to the Handy album, “Satch Plays Fats” had the potential to match or top its predecessor, but a number of factors hindered its success. One issue was the repertoire. Armstrong had suggested several of Waller’s great instrumental pieces, including “Zonky”, “Minor  Drag” and “Stealin’ Apples”. Avakian wrote that “we decided against doing any instrumentals, agreeing that they would break the mood we both felt the album should create.” It is assumed that “we” referred to Avakian and Armstrong, but it sounds like a decision emanating from over Avakian’s head (possibly Mitch Miller?). The instrumentals hardly broke the mood on the Handy LP, and including Waller instrumentals might have reminded listeners that Waller was primarily a great jazz pianist and composer. Waller’s vocal records were strictly a commercial enterprise, and the idea of making Armstrong’s Waller tribute an-all vocal affair sounds like a disingenuous ploy to squeeze as much money out the project as possible. As it turned out, the All-Stars were exhausted when they recorded “Satch Plays Fats”, having just concluded a tour and about to face another engagement which would break up the string of recording sessions. The All-Stars had the same personnel as on the Handy album, but changes would happen a few months after “Satch Plays Fats”. The problem was Barney Bigard, whose alcoholism was getting worse. Apparently, alcohol made him more of an introvert, and throughout the album, we can hear that Bigard virtually disappears within the ensembles. On some of the tracks, the rhythm section audibly holds back behind the clarinetist, and as the soloist who usually followed Bigard, Young showed his flexibility by playing in a calmer manner. Eventually, someone (perhaps Avakian?) decided that the band need not maintain the lower volume after Bigard’s solos, allowing Deems to raise the dynamics with powerful backbeats. Would a push of new material have encouraged Bigard to recover his well-known fluency? Probably not, as the tunes that were recorded seem to have been all the challenge Bigard and the band were willing to face.

Drag” and “Stealin’ Apples”. Avakian wrote that “we decided against doing any instrumentals, agreeing that they would break the mood we both felt the album should create.” It is assumed that “we” referred to Avakian and Armstrong, but it sounds like a decision emanating from over Avakian’s head (possibly Mitch Miller?). The instrumentals hardly broke the mood on the Handy LP, and including Waller instrumentals might have reminded listeners that Waller was primarily a great jazz pianist and composer. Waller’s vocal records were strictly a commercial enterprise, and the idea of making Armstrong’s Waller tribute an-all vocal affair sounds like a disingenuous ploy to squeeze as much money out the project as possible. As it turned out, the All-Stars were exhausted when they recorded “Satch Plays Fats”, having just concluded a tour and about to face another engagement which would break up the string of recording sessions. The All-Stars had the same personnel as on the Handy album, but changes would happen a few months after “Satch Plays Fats”. The problem was Barney Bigard, whose alcoholism was getting worse. Apparently, alcohol made him more of an introvert, and throughout the album, we can hear that Bigard virtually disappears within the ensembles. On some of the tracks, the rhythm section audibly holds back behind the clarinetist, and as the soloist who usually followed Bigard, Young showed his flexibility by playing in a calmer manner. Eventually, someone (perhaps Avakian?) decided that the band need not maintain the lower volume after Bigard’s solos, allowing Deems to raise the dynamics with powerful backbeats. Would a push of new material have encouraged Bigard to recover his well-known fluency? Probably not, as the tunes that were recorded seem to have been all the challenge Bigard and the band were willing to face.

Mosaic’s discography shows a preponderance of false starts, breakdowns and alternate takes for the Waller project (most of which stayed in the vault). Only the album closer, “Ain’t Misbehavin’”, was presented on the original LP in one unedited take, and the rest were pieced together by Avakian in the editing room. Avakian’s studio techniques had Armstrong doing everything from the superhuman (the immediate switch from vocal to trumpet on the magnificent “Blue Turning Grey Over You”) to the completely impossible (Armstrong’s overdubbed trumpet obbligato on “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now” and the vocal duet with himself(!) on “I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling”) but Avakian’s greatest feat was assembling masterpieces from the very good—but usually flawed—raw takes.

For his part, Armstrong arrived prepared and inspired. The previously unissued takes reveal Armstrong in prime form, improvising new solos on nearly every take, including some that were equal to Avakian’s edited creations (When the Brooks-produced CD of “Satch Plays Fats” appeared in 1986—with alternate takes subbing for the still-missing masters—British trumpeter and jazz historian Humphrey Lyttelton declared that he preferred the alternate to the master). If there was ever a prime example of latter-day Armstrong regaining the artistic heights he reached in the 1920s, “Satch Plays Fats” is it. As in the old days, the listener is riveted to the rich tone of his trumpet and his expressive voice. For examples of the latter, listen to his vocal choruses on this album. Armstrong assumes that his listeners either know the lyrics, or can predict the rhymes…so he leaves them out, inserting a break for a scat fill rather than simply finishing the line. And while we’re on the subject of vocals, the perpetually under-rated Velma Middleton deserves credit for her fine singing and musicianship on this album. The first take of “Squeeze Me” finds Middleton struggling with the verse’s melody (Avakian even sings it to her at one point!) She still doesn’t quite have it down on that take, but she corrected the problem between takes and nailed it on the master. Middleton was no Ella Fitzgerald, but she possessed a similar drive for musical excellence. Middleton died in 1961 while on tour with Armstrong, so she was dedicated, too.

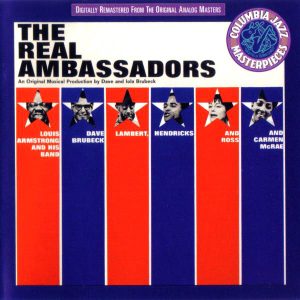

From 1955-1959, all of Armstrong’s recordings for Columbia (save the sessions discussed above) were live performances, which were eventually collected on Mosaic’s now out-of-print live Armstrong set. Avakian remained Armstrong’s producer until he left Columbia in 1957. When Armstrong returned to the Columbia studios in September 1961 for a spectacular collaboration with Dave Brubeck, he had a nearly-new edition of the All-Stars (only Young and Kyle remained from the earlier Columbia studio sessions) and a new producer, Teo Macero. In time, Macero would become even more deft with the editing razor blade than Avakian, but on the Armstrong/Brubeck LP, “The Real Ambassadors”, many of the tracks were released as they went down in the studio, with many fewer inserts and splices than on an Avakian project. Mosaic’s presentation of this album is slightly different than the other LPs: instead of presenting complete takes which were partially used by Avakian, the supplemental section for “Ambassadors” includes takes that have never been heard before, even in part. There are several interesting episodes in this section, including a couple of naughty tags for “Good Reviews”, extra trumpet spots for Armstrong on several tunes, and a wonderful 8-minute composite of Armstrong’s heart-rending vocal on “Summer Song”.

remained Armstrong’s producer until he left Columbia in 1957. When Armstrong returned to the Columbia studios in September 1961 for a spectacular collaboration with Dave Brubeck, he had a nearly-new edition of the All-Stars (only Young and Kyle remained from the earlier Columbia studio sessions) and a new producer, Teo Macero. In time, Macero would become even more deft with the editing razor blade than Avakian, but on the Armstrong/Brubeck LP, “The Real Ambassadors”, many of the tracks were released as they went down in the studio, with many fewer inserts and splices than on an Avakian project. Mosaic’s presentation of this album is slightly different than the other LPs: instead of presenting complete takes which were partially used by Avakian, the supplemental section for “Ambassadors” includes takes that have never been heard before, even in part. There are several interesting episodes in this section, including a couple of naughty tags for “Good Reviews”, extra trumpet spots for Armstrong on several tunes, and a wonderful 8-minute composite of Armstrong’s heart-rending vocal on “Summer Song”.

Dave and Iola Brubeck started writing the script of “The Real Ambassadors” in 1957, shortly after Armstrong rebuked President Dwight Eisenhower for his stand on the Little Rock integration crisis. Armstrong was involved in the US State Department’s Jazz Ambassadors program, but he cancelled a tour of the USSR in protest. “The Real Ambassadors” was designed as a Broadway show starring Armstrong which would strongly support Armstrong’s stance on civil rights, as well as his importance as a jazz icon and musical ambassador. The cast eventually included Carmen McRae as Armstrong’s band singer and love interest, Trummy Young as an advisor, and Lambert, Hendricks & Ross as a Greek chorus. The Dave Brubeck Trio and the Armstrong All-Stars provided instrumental backup. Unfortunately, the show was never staged in Armstrong’s lifetime, and the sole concert performance at the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival went unrecorded (Historians still argue whether Joe Glaser or Dave Brubeck was at fault for not hiring the video crew already in place at the festival). The only tangible remnant of the show was the Columbia LP and a vocal score published years later.

Trummy Young as an advisor, and Lambert, Hendricks & Ross as a Greek chorus. The Dave Brubeck Trio and the Armstrong All-Stars provided instrumental backup. Unfortunately, the show was never staged in Armstrong’s lifetime, and the sole concert performance at the 1962 Monterey Jazz Festival went unrecorded (Historians still argue whether Joe Glaser or Dave Brubeck was at fault for not hiring the video crew already in place at the festival). The only tangible remnant of the show was the Columbia LP and a vocal score published years later.

Columbia gave the album the deluxe treatment, but it did not include a synopsis or lyrics in the gatefold package. While Iola Brubeck’s witty lyrics give the basic plot points, many of the words go by so fast that they are lost to the casual listener (part of that problem is due to the tongue-twisting nature of the words, and the rest is the sloppy diction of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross). To guide the listeners, Riccardi provides a thumbnail synopsis (those looking for more plot details should refer to Philip Clark’s Brubeck bio, “A Life in Time”) and Mosaic’s engineers have made some improvements to the overall sound.

Armstrong and the Brubecks had corresponded with ideas and newly composed music since Dave’s initial meeting with Armstrong in 1959. There’s not a lot of Armstrong’s trumpet on the set, but what’s there is spectacular (specifically an upper-register rendition of “The Duke”—here re-titled “You Swing Baby”—and the series of high F’s in the finale). Apart from a few lyric fluffs here, Armstrong is in very good voice as he carries the weight of the show. Carmen McRae is also in fine form, and her duets with Armstrong demonstrate true chemistry, despite a considerable age difference. Trummy Young steps into a role probably designated for the late Velma Middleton, but years of watching the Armstrong/Middleton act prepared him for the role. The weak links are Lambert, Hendricks and Ross, which was always more of a collection of soloists rather than a true vocal group. As a trio, they showed no sense of ensemble (even for basic tasks, like starting and stopping together) and their intonation was dreadful. Down Beat had named LH&R the “hottest new group in jazz”, and Columbia used the quote as the title for the trio’s debut album, so I understand the desire to use them for this project. However, they just couldn’t sing this music (their attempt at singing religious chant on “They Say I Look Like God” is just painful) and Columbia could have easily hired any of the many professional vocal groups of the time to perform this music.

With its companion live set, Mosaic’s collection of Armstrong’s Victor and Columbia studio sessions offers undeniable proof of Ricky Riccardi’s theory that Louis Armstrong was a major creative force throughout his career. Riccardi’s unfettered enthusiasm for his subject has revived interest in Armstrong’s music from his later years. Now that Riccardi has been hired to complete a three-volume biography of Armstrong, he will continue to illuminate listeners of the many wonders of Armstrong’s discography. Armstrong has found his Boswell, even though they never met in person.

and Columbia studio sessions offers undeniable proof of Ricky Riccardi’s theory that Louis Armstrong was a major creative force throughout his career. Riccardi’s unfettered enthusiasm for his subject has revived interest in Armstrong’s music from his later years. Now that Riccardi has been hired to complete a three-volume biography of Armstrong, he will continue to illuminate listeners of the many wonders of Armstrong’s discography. Armstrong has found his Boswell, even though they never met in person.