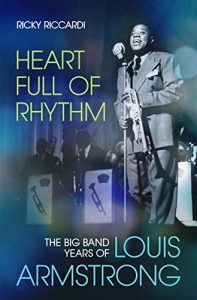

The 2011 publication of Ricky Riccardi’s book, “What a Wonderful World” (Pantheon) called upon jazz fans and historians to rethink their long-held beliefs about Louis Armstrong’s music of the Fifties and Sixties. Many had written off the work of Armstrong’s All-Stars as a commercial and watered-down version of the trumpeter’s greatest work. Armed with abundant enthusiasm and solid research, Riccardi endeavored to set the matter straight. While my review of the book criticized Riccardi’s jingoism and occasional far-reaching claims, there’s no denying the impact of Riccardi’s work: he has become the go-to man for all things Armstrong. Riccardi is now the Director of Research Collections for the Louis Armstrong House Museum, and he has produced a series of extraordinary Armstrong reissues (including a stunning 9-CD Mosaic collection of live performances from the All-Star era, with a companion set of studio performances due within the next few weeks). In a rather surprising move, a competing publisher, Oxford, commissioned Riccardi to continue his work as Armstrong’s biographer. The current result, “Heart Full of Rhythm”, discusses Armstrong’s big band period of 1929-1947. A final volume, covering Armstrong’s early years, will doubtlessly follow, creating an  unusual scenario where a major artist’s life is presented in reverse order by (at least) two separate publishers!

unusual scenario where a major artist’s life is presented in reverse order by (at least) two separate publishers!

Armstrong’s big band era may have been more misunderstood than his All-Star period. From 1929 until his forced layoff in 1934, Armstrong created a series of recordings where ordinary pop songs were transformed into solo vehicles, allowing him to dazzle the world with bravura trumpet solos and exquisitely phrased vocals. These recordings taught jazz style to both established and rising musicians. Additionally, these recordings—now issued on Brunswick’s main pop line, rather than the “race” series—attracted a larger audience for Armstrong. Combined with an expanded touring schedule, Armstrong soon vaulted to the top of the show business roster. Armstrong drew large crowds in appearances across the US and in Europe, and had his embouchure not failed him in 1934, he might have continued that pattern for many years. However, the endless strings of high C’s which Armstrong played in showpieces like “Tiger Rag” eventually took its toll; when he returned to playing in 1935, he regained much of his former strength, but offered less flashy examples of his technique. While his lips gave him trouble for the rest of his life, Armstrong could still thrill audiences with the rich sound of his open horn…plus, he could sing and tell jokes. This truly marked the beginning of the Armstrong era which Gary Giddins aptly dubbed “The Artist as Entertainer”.

Riccardi follows Giddins’ lead with a highly detailed examination of Armstrong’s music and activities. Without losing any of his zeal, Riccardi makes well-considered arguments to counter the negative press of the past. He acknowledges the strong support Armstrong received from the black press, and notes that white publications (including “Down Beat” and “Metronome”) frequently bashed Armstrong’s performances without due reason. Riccardi takes particular aim at Leonard Feather, a critic notorious for praising an artist when presenting them on stage, and mercilessly berating them in a published review of the same event! (My own experience with Feather in 1983 found him pulling the exact same stunt—and getting well-deserved flak from the artistic community in return). Armstrong could hold grudges for years, but even after Feather published a devastating review of Armstrong’s performance at the 1944 Esquire All-Star Jazz Concert, Feather was somehow welcomed into the trumpeter’s home the following year to write an extended interview. Earlier in the narrative, Riccardi unravels the stories of Armstrong’s struggles with two competing managers, and shows how the problems continued years after Joe Glaser took over Armstrong’s bookings. He also acknowledges Armstrong’s philandering, and the effect it had on three marriages.

A healthy portion of the book discusses Armstrong’s recordings, and it is here that we can see Riccardi’s growth as a writer and historian. He seems much more willing to accept the bad sides with the good. Rather than letting his enthusiasm lead the way, he trusts his ears and his exemplary knowledge to offer a balanced overview of Armstrong’s music. There is no doubt that Armstrong’s recordings of this period were uneven, but many of the backup bands were not as awful as reported. Armstrong appreciated good musicians, and he knew that the overall effect of his performances—live or recorded—would ultimately reflect on him. The bands led by Luis Russell, Zilner Randolph, Joe Garland and Teddy McRae all had their share of high and low points, all of which are duly noted by Riccardi. In the 1940s, Armstrong hired young modernists like Charles Mingus, Kenny Clarke and Dexter Gordon. Riccardi discusses the Armstrong tenures of each of these young lions showing the empathy from boss to sideman which overrode the debates between traditional and modern jazz. As a style, bop gets some unwelcome criticism in Riccardi’s account: the silly notion that bop’s main objective was to create music that older musicians couldn’t play (bop was much more than that—it was a musical evolution with roots going back to swing players like Teddy Wilson and Coleman Hawkins); the long-disproven story that the Dizzy Gillespie/Charlie Parker engagement at Billy Berg’s in Hollywood was a total flop (California had plenty of bop fans back then; otherwise, the explosion of modern music on LA’s Central Avenue wouldn’t have occurred, let alone the beginning of Jazz at the Philharmonic); and the nonsensical idea that bop was finished by 1949 with Gillespie and Parker both moving towards more commercial music (If that were true, why is the bop language still considered the lingua franca among today’s musicians?). Of course, bop has been ridiculed in every previous Armstrong biography, and as noted, Riccardi offers some balance in showing Armstrong’s acceptance of the young musicians. I just hoped that the scales would have been a little more even.

Like its predecessor, “Heart Full of Rhythm” is not a perfect book, but both of Riccardi’s books contain more strengths than weaknesses. His bright (and occasionally raw) style conveys his love of Armstrong, his music and jazz in general. Riccardi was born 9 years too late to meet his idol, but that has not stopped him from gathering an unparalleled knowledge of Armstrong and making much of the icon’s recorded legacy available to the public. Louis Armstrong is lucky to have such a dedicated biographer.