It was hot in the summer of 1960, but it wasn’t because of the weather. In the United States, the Civil Rights movement transitioned into a new phase with the sit-in, a form of passive resistance which forced change in pockets of the South. The sit-in had an elegant simplicity: a group of Black students would walk into a diner and take their seats at the lunch counter. As Blacks were prohibited from sitting at the counter, the white employee would tell them to move, and when the Blacks didn’t comply, the whites would ignore their requests for food service. The Black students stayed put until the white patrons got angry enough to throw them out, an act usually captured by television news cameras. The sit-in forced the actions of the whites, who had little choice but to follow their pre-destined roles, and the concept hit the white owners right where it hurt: in their wallets. The seats normally taken by paying white patrons were filled by Blacks, who would have payed and left if given the opportunity. The sit-ins had started in February, and by the summer, several Southern towns got the message and integrated their lunch counters. Meanwhile in Washington, outgoing President Dwight Eisenhower tried to push a new Civil Rights Bill through Congress, but efforts by Southern Democrats successfully weakened the bill to the point of ineffectiveness. 1960 was an election year, but unlike today’s campaigns, no one knew who the new candidates would be. In the second week of July, the Democratic party gathered in Los Angeles to decide on their candidate (from a field of seven contenders).

At the same time that the Democrats were huddling in California, the Charles Mingus Quintet was temporarily out of the country. They had been booked to play at an open-air jazz festival in the south of France. For European audiences, this was their first exposure to a band fully entrenched in the avant-garde movement (usually inarticulately referred to in the press as “the new thing”). It was a risky venture: John Coltrane, who would soon become a major figure in avant-garde jazz, had played in Paris in the previous March as part of the Miles Davis Quintet, and his experimental solos had been booed by French audiences. Mingus’ music was more visceral than that of Davis and Coltrane, and the members of Mingus’ group—Ted Curson (trumpet); Eric Dolphy (reeds); Booker Ervin (tenor sax); Mingus (bass, piano); and Dannie Richmond (drums)—mixed the emotions of roots music with the power of free jazz. The resulting music was electrifying, and while the Antibes performance was recorded and filmed, it was not issued in full until after Mingus’ death in 1979.

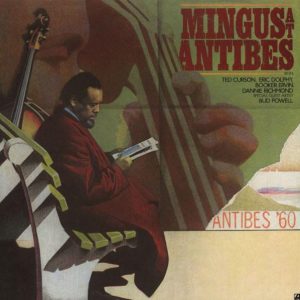

The Atlantic 2-LP set, “Mingus at Antibes” captured the Mingus Quintet in top form. The band had developed a strong sense of collective improvisation through a long residency at the New York nightclub, the Showplace. The playlist at Antibes included two superb compositions that had not yet been recorded (and were thus still in development), another piece that just been recorded six weeks earlier, two pieces which had been in the book for about a year, and a throwback to the bop era, featuring a guest appearance by one of the era’s greatest icons. The fire and intensity of the performance is apparent even when listening to “Mingus at Antibes” in isolation; try listening to it after listening to the considerably energetic Mingus studio album, “Blues and Roots”, and the power of the Antibes concert is simply overwhelming.

The Atlantic 2-LP set, “Mingus at Antibes” captured the Mingus Quintet in top form. The band had developed a strong sense of collective improvisation through a long residency at the New York nightclub, the Showplace. The playlist at Antibes included two superb compositions that had not yet been recorded (and were thus still in development), another piece that just been recorded six weeks earlier, two pieces which had been in the book for about a year, and a throwback to the bop era, featuring a guest appearance by one of the era’s greatest icons. The fire and intensity of the performance is apparent even when listening to “Mingus at Antibes” in isolation; try listening to it after listening to the considerably energetic Mingus studio album, “Blues and Roots”, and the power of the Antibes concert is simply overwhelming.

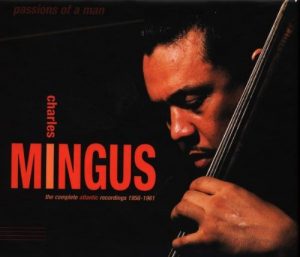

The original LPs and the single CD reissues jumbled the tune order [Wednesday/Prayer/Love/April/Folk/Git]. While the disc sequence is highly effective, Mingus’ original programming—followed on the Rhino/Atlantic complete collection, “Passions of a Man” and in the discussion below—brings out different facets of the music. The opening piece “Prayer for Passive Resistance” immediately cements the bonds between the band, the sanctified church and civil rights. The initial recording from late May 1960 featured saxophonist Yusef Lateef, but Ervin probably played this piece at the Showplace, and at Antibes, he makes it his own. The live performance starts with a rhythmic bass introduction before Ervin takes the spotlight. He starts at a relatively low volume, but he picks up momentum when he starts to improvise. Mingus and Richmond change up the background; that and the riffing horns help Ervin build the excitement and intensity. Mingus shouts encouragement to Ervin, and the tenor man responds to everything—musical and verbal—that Mingus throws at him. Ervin’s pacing is exquisite throughout this 8-minute feature: there are several places where it sounds like he’s ready to stop, but he immediately restarts, as if he was turning the page and beginning a new chapter.

The sacred connection continues with “Better Git Hit in Your Soul”. Ted Curson starts the solo sequence, mixing half-valve effects and a fat trumpet tone with the expressive language of the new jazz. Ervin’s solo is accompanied with a 12/8 clapping pattern on which the audience joins in almost instantly. Mingus recognized a good thing and he reprised the pattern several times during the concert. Eric Dolphy was the most harmonically advanced of the horn men, and the combination of his blazing technique and strongly vocalized alto sax tone are still impressive today (it must have been quite a shock to the French audiences!) A pair of short and fiery Dannie Richmond drum solos frame an interlude. But after the reprise of the melody, there is another surprise: Mingus has put down his bass, and sat at the piano, playing a sequence of low rumbling chords while Richmond goes wild behind the drums. Mingus returns to the bass, the tune comes back, and Mingus—happily singing along—picks up his bow and adds an extended sequence of “Amen”s to close the performance.

“Wednesday Night Prayer Meetin’” is—like the pieces that preceded and followed it—a blues in F. Curson is much more fluid on his horn than before, spewing out abstract lines and working off the background riffs of Ervin and Dolphy. Ervin’s moaning and wailing evoke a vocal response from Mingus. Then Dolphy increases the emotion, as his multitude of notes symbolize flowing tears. Mingus sings an imitation of Dolphy, and as the rhythm section cooks with ferocity, the horns cry like Dolphy. Richmond plays another short solo, and before long, Mingus is back at the piano alternating unison lines with the horns and low-register tone clusters. Richmond lets loose again, showing his astounding technique (in 1960, he had only been a drummer for a few years). And as on “Better Git Hit”, the coda features another “Amen” exchange.

“Folk Forms” remained untitled until its official recording for Candid in October 1960. It remains one of my favorite Mingus compositions. It has no discernible melody and is held together by a recurring four-note rhythm. While each section opens with a soloist, there really aren’t any solos because the other players enter and interact, resulting in rambunctious and joyful collective improvisations. Basically, Mingus is pulling us back to the earliest years of the music as he connects his progressive jazz ensemble with that of a traditional New Orleans jazz band. Mingus had long recognized the validity of traditional jazz—he worked with Kid Ory and Louis Armstrong during his early years in Los Angeles—but was it the appearance at Antibes of a New Orleans band led by Mingus’ Atlantic labelmate, Wilbur DeParis, that inspired the bassist to create this audacious mixture of progressive and traditional jazz? We may never know, but the Antibes recording remains the first known recording of “Folk Forms”. Many of the elements which marked the Candid recording are here—the implied backbeat, the rhythm section’s sparse but persistent accompaniment, the four-note motive bouncing all over the band, the ecstatic collective improvisations—however, the individual episodes are much shorter, and they reach their emotional peaks much too soon. Ervin never starts a solo episode, and while he participates within the collective improvisations, it sounds like he might not have completely grasped Mingus’ concept. Significantly, he was not part of the group that recorded this piece three months later.

Ervin does not play on “What Love?” (the other piece from Antibes recorded for Candid in October) Composed in 1946, “What Love” was the most progressive selection on the concert. The slow, mournful melody (based on an expansion of “What is This Thing Called Love”) leads to a rich-toned Curson solo, which freely moves between tempos while Dolphy—now on bass clarinet—adds a solemn counter-melody. Mingus takes over from Curson with a solo that simultaneously displays his virtuosity and sensitivity—two attributes which don’t always align, but do here. When Dolphy re-enters for an extended duet with Mingus, he retains the mood for a few minutes, but eventually his sound grows more agitated and the conversation becomes more speech-like. The audience starts whistling and talking back to the band. At least one writer claims that the crowd booed Dolphy and Mingus, but I can’t hear any such sounds on the recording. However, we can be certain that there was some confusion in the audience, which doubtlessly led to long discussions about this piece long after the concert ended.

The last piece brings a distinguished guest to the bandstand, Bud Powell. Powell was one of bebop’s great trailblazers, influencing pianists for decades to come, but in 1960 his brilliance was dimmed by ongoing mental health issues. He had moved to Paris in 1959, and with the help of his friend Francis Paudras, he was attempting to rebuild his focus and technique. For his appearance with Mingus, he played on an extended jam on “I’ll Remember April”, a tune he had played on many occasions. It was also a tune that had been played and recorded by Powell’s brother Richie, when he was pianist with the Clifford Brown/Max Roach Quintet. The Brown/Roach Quintet was the premier bop combo of its day, and the band came to a tragic ending when Brown and Powell were killed in an automobile accident in June 1956. In 1960 on the stage at Antibes, the Mingus band with Bud Powell suddenly recreates the past, and even though only four years had passed since the Brown/Roach recording, the stylistic shift is seismic. Of course, all of the musicians knew the older style and played it flawlessly. Powell is in very good form, executing clean lines with his right hand over the spare comping by his left hand. Curson didn’t have Clifford Brown’s technique, but he captures some of the late trumpeter’s singing tone in his brief solo. Dolphy’s alto solo contains his unique note choices, but is much more conservative than his other recordings of the period. Ervin returns for a solo exchange lifted directly from the Brown/Roach recording: four-bar exchanges leading to twos, and ones (Richmond’s stop-time episodes prevent it from being a total copy). Curson joins in for a collective improvisation before the final chorus. The band plays the A section of the melody, and perhaps Powell missed the cue to stop, for the performance stumbles to an end mid-way through the bridge. The flawed ending does little to mar the excellence of the overall concert.

It was said that the “conversation” (more like an argument) on the Candid  version of “What Love” was Dolphy telling Mingus that he was leaving the band. He did leave, working with two other major figures of the avant-garde, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane, within a year. Eventually, Dolphy came back to the Mingus group, most notably on a 1964 European tour from which he never came home. He died after falling into a diabetic coma in Berlin. He had just turned 36 years old nine days earlier. Ted Curson and Booker Ervin moved to solo careers, but neither reached the artistic heights they had with Mingus. Ervin died in 1970; Curson passed in 2012. Powell never fully recovered his artistic stature, and he died alone in a New York hospital in 1966. Mingus was at his creative zenith in 1960, and that period lasted for another four to five years, but things fell apart for a few years before he re-emerged for a career renaissance in the early 1970s. He died of Lou Gehrig’s Disease (ALS) in 1979. Dannie Richmond stayed with Mingus until the bassist’s death, and then became the first leader of the tribute band, Mingus Dynasty. 60 years later, the musicians have all left us, but their music remains through small plastic discs. The only other thing left from those days is racism. Just turn on the TV and you’ll see the latest version of the Civil Rights struggle.

version of “What Love” was Dolphy telling Mingus that he was leaving the band. He did leave, working with two other major figures of the avant-garde, Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane, within a year. Eventually, Dolphy came back to the Mingus group, most notably on a 1964 European tour from which he never came home. He died after falling into a diabetic coma in Berlin. He had just turned 36 years old nine days earlier. Ted Curson and Booker Ervin moved to solo careers, but neither reached the artistic heights they had with Mingus. Ervin died in 1970; Curson passed in 2012. Powell never fully recovered his artistic stature, and he died alone in a New York hospital in 1966. Mingus was at his creative zenith in 1960, and that period lasted for another four to five years, but things fell apart for a few years before he re-emerged for a career renaissance in the early 1970s. He died of Lou Gehrig’s Disease (ALS) in 1979. Dannie Richmond stayed with Mingus until the bassist’s death, and then became the first leader of the tribute band, Mingus Dynasty. 60 years later, the musicians have all left us, but their music remains through small plastic discs. The only other thing left from those days is racism. Just turn on the TV and you’ll see the latest version of the Civil Rights struggle.