By the mid-1960s, both pianist Lennie Tristano and saxophonist Lee Konitz were established figures in jazz—Tristano as a highly influential teacher and Konitz as one of the music’s most original improvisers. The two men were constantly grouped together because of their decades-long association: first as teacher and pupil, then as leader and sideman. Tristano never had a better student than Konitz, who amplified Tristano’s methods through his own original sound and approach. It may seem surprising that they never made a duet recording together, but soon after their last gig together, both men started an album of duets…with other musicians. Konitz’ album was recorded in one day, and released soon thereafter; Tristano’s project covered 8-9 years, and is being issued now for the first time.

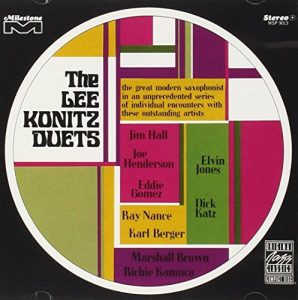

For the 1967 Milestone album, “The Lee Konitz Duets” (OJC 466), the saxophonist surrounded himself with nine outstanding musicians. Not content  to simply record a series of encounters with his favorite players, Konitz organized the material to include ensemble pieces which offered changes in timbre and approach. Further, Konitz brought three different horns to the studio (alto, tenor and baritone saxes) along with a then-popular electronic device called the Varitone, which allowed him to play his horns in parallel octaves. The music incorporates a wide variety of styles from New Orleans to free, and the directions taken in each duet are sometimes quite surprising. The album opens with a delightful tribute to Louis Armstrong on “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue”. Without any backing rhythm, Konitz’ alto and Marshall Brown’s valve trombone weave intricate improvised lines while staying within the tune’s original harmony. At the last chorus, the two voices unite to play Armstrong’s classic trumpet solo, over their overdubbed background played on baritone sax and euphonium. The jocularity leads to intensity on “You Don’t Know What Love Is”, where Konitz’ piercing (and pitched slightly sharp) alto is paired with tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson. Despite the different horns, both men seem to work around the same pitch level, and it weren’t for the stereo separation of the two, it might be difficult to separate the individual lines.

to simply record a series of encounters with his favorite players, Konitz organized the material to include ensemble pieces which offered changes in timbre and approach. Further, Konitz brought three different horns to the studio (alto, tenor and baritone saxes) along with a then-popular electronic device called the Varitone, which allowed him to play his horns in parallel octaves. The music incorporates a wide variety of styles from New Orleans to free, and the directions taken in each duet are sometimes quite surprising. The album opens with a delightful tribute to Louis Armstrong on “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue”. Without any backing rhythm, Konitz’ alto and Marshall Brown’s valve trombone weave intricate improvised lines while staying within the tune’s original harmony. At the last chorus, the two voices unite to play Armstrong’s classic trumpet solo, over their overdubbed background played on baritone sax and euphonium. The jocularity leads to intensity on “You Don’t Know What Love Is”, where Konitz’ piercing (and pitched slightly sharp) alto is paired with tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson. Despite the different horns, both men seem to work around the same pitch level, and it weren’t for the stereo separation of the two, it might be difficult to separate the individual lines.

The remainder of side one is a series of variations on “Alone Together”. Konitz starts alone with the Varitone alto. The fuzzy sound of the gizmo is a shock to the ears after two tracks of clear alto tone, but the greater surprise that Konitz abandons the tune almost immediately. He switches to tenor for the duet with Elvin Jones, and as on Henderson’s duet, there is so much going on that it is hard to comprehend it all in one sitting. While the two musicians are clearly working off each other’s lines, there’s also a sense of competition in this variation as Konitz and Jones seem to have different messages that they are trying to convey at the same time. The variation with vibraphonist Karl Berger and Konitz (back on alto) trades power for intricacy. The lines are very concentrated here, and at one point, Konitz blurs those lines by imitating the metallic sound of Berger’s instrument by rattling the keys of his saxophone. Eddie Gomez was not well-known at the time of this recording—his tenure with Bill Evans began in the previous year—and his astounding technique, which alternates flamenco-like passages with rich bowed lines, must have stunned listeners back then. Konitz compliments Gomez with flurries of notes on alto (the credits claim tenor, but the high notes are out of the larger horn’s range). The communication between the two men is quite acute in the central episode where the lines appear to move from one instrument to another. The final variation brings together the entire quartet. Except for Konitz’ repetitions of the main motive, the melody of “Alone Together” has basically vanished. Instead, the band moves into a prototype of free-bop, with all the musicians improvising away from the chord structure. The energy is palpable, with each line competing for our attention.

The second side opens with pianist/producer Dick Katz performing his original “Checkerboard” with Konitz on alto. The jagged phrase lengths of the melody remind me of the tunes Tristano and Konitz played together in the 1940s and 1950s, and while Katz sounds nothing like Tristano here, the strong linear interaction between saxophone and piano makes me wonder how much different a Tristano/Konitz duet would have been. Jim Hall’s “Erb” (an original tribute to classical composer Donald Erb) is a highly concentrated work where the lines remain sparse but closely intertwined. Hall brought this piece into the studio as a graphic score, rather than in traditional music notation. The mood breaks with a swinging two-tenor rendition of Lester Young’s “Tickle Toe”, with guest Richie Kamuca. This duet is in line with the opening “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue” with its first choruses devoted to simultaneous improvisation and the composer’s famous solo used as an out-chorus. I don’t know how Duke Ellington’s violinist Ray Nance was convinced to take on a free improvisation with Konitz, but the resulting piece, “Duplexity”, is a fascinating experiment. As with some of the “Alone Together” variations, Nance’s and Konitz’ lines are sometimes in competition with each other, but it’s amazing to hear how many times their lines converge and intersect. The track is not a total success—Konitz’ funky obbligatos are usually at odds with Nance’s elegant bowed lines—but when these two voices connect, the effect is stunning. Marshall Brown’s “Alphanumeric” provides the vehicle for final solo turns by all of the principals (save Nance). The soloists split off into groups of two or three for improvised episodes, and the section featuring the rhythm section is particularly well executed. Through overdubbing, Konitz duets with himself on Varitone, alto and tenor—a self-indulgent effect which adds to the already dense texture. At the end, the other instruments fall out and the album ends with Konitz improvising alone on Varitone as the engineer fades out. Konitz, who recently died at 92 from COVID-19, left behind an enormous discography. Still, it is not hard to pronounce “The Lee Konitz Duets” as one of his most focused and finely executed projects.

“The Duo Sessions” (Dot Time 8016) fills an important gap in Tristano’s discography. With the exception of an album of vocal accompaniments, there were no issued recordings of Tristano after 1966. “The Duo Sessions” includes  sessions from 1967 and/or 1968 (with drummer Roger Mancuso), 1970 (with tenor saxophonist Lenny Popkin) and 1976 (with pianist Connie Crothers). Taking the sessions in chronological order, the Mancuso session finds Tristano’s right hand lines as clear and exciting as ever. Tristano’s rhythmically powerful improvisations energize “Session”, “My Baby” and “Palo Alto Street”, even without the propulsive walking bass lines that marked his pivotal 1961 Atlantic LP “The New Tristano”. Early in his career, Tristano instructed his drummers to play brushes on the snare and to avoid dropping bombs; I wish he would have given the same instruction to Mancuso, for the abundance of cymbals and sticks-on-snare chatter cover up the intricacies of Tristano’s lines. It sounds like these tracks came from at least two sessions, for starting with the fifth track, “Imagery”, the balance is significantly better with more emphasis on piano. This second session also includes hints of Tristano’s left hand lines, but not played with the power as on “The New Tristano”. His best solo here is doubtlessly “Minor Pennies” where his lightning-fast right-hand lines are punctuated with jabbing block chords.

sessions from 1967 and/or 1968 (with drummer Roger Mancuso), 1970 (with tenor saxophonist Lenny Popkin) and 1976 (with pianist Connie Crothers). Taking the sessions in chronological order, the Mancuso session finds Tristano’s right hand lines as clear and exciting as ever. Tristano’s rhythmically powerful improvisations energize “Session”, “My Baby” and “Palo Alto Street”, even without the propulsive walking bass lines that marked his pivotal 1961 Atlantic LP “The New Tristano”. Early in his career, Tristano instructed his drummers to play brushes on the snare and to avoid dropping bombs; I wish he would have given the same instruction to Mancuso, for the abundance of cymbals and sticks-on-snare chatter cover up the intricacies of Tristano’s lines. It sounds like these tracks came from at least two sessions, for starting with the fifth track, “Imagery”, the balance is significantly better with more emphasis on piano. This second session also includes hints of Tristano’s left hand lines, but not played with the power as on “The New Tristano”. His best solo here is doubtlessly “Minor Pennies” where his lightning-fast right-hand lines are punctuated with jabbing block chords.

The Popkin session is much more successful. The roles are clearly delineated and the two musicians are not fighting each other to be heard. Popkin’s sound is straight out of Warne Marsh, and like the elder tenor man, Popkin instinctively knows the way to follow the pianist when he shifts the harmony. While the performances swing, Popkin and Tristano seem less tied to an unchanging ground beat, placing more commitment to the purity of the lines. “Ballad”—based (somewhat) on “These Foolish Things”—sounds like a throwback to some of Tristano’s late 1940s standard sides, where the harmonies were so obscured that Tristano could claim them as original compositions. “Chez Lennie” (an “All the Things You Are” contrafact) features a leaping solo from Popkin with seemingly unending lines spilling out of his tenor. Tristano fails to maintain the momentum, and the track meanders to an unsatisfying conclusion. Like many of Tristano’s home recordings, many of these pieces sound like excerpts from longer improvisations. Unfortunately, some of these tracks could have used further editing for a greater overall effect. Not so for “Melancholy Stomp” though, where the two men have a great deal of fun negotiating a tricky harmonic sequence. The communication between the two is outstanding and their simultaneous improvisations are thrilling. The two-piano meeting with Crothers is called “Concerto” and split into two unequal parts. It is a curious piece, primarily free, and never giving up that style even when straight-ahead swing or slow ballad are set up. I’m not sure anyone will revise their appreciations of Tristano from this CD, but it is a welcome addition to his legacy.