MICHAEL COX: “COMPASSION” (CoJazz 1047)

Saxophonist Michael Cox lives in Columbus, Ohio, where he teaches at Capital University and performs in Byron Stripling’s Columbus Jazz Orchestra. Cox’s second album, “Compassion” has been in the works for the past four years. Originally, pianist/composer Mark Flugge was scheduled to play on the album. However, Flugge suddenly passed away in May 2014 from a variety of illnesses, and the wife of Cox’s preferred drummer, Matt Wilson, died a month later. It would be a little over a year before Cox and Wilson made it into a New Jersey studio to record the album. They were fortunate enough to add two other iconic players to the group: keyboardist Gary Versace and bassist Buster Williams. Inspired by these great musicians—who wouldn’t be?—and by the works of Flugge and another fine composer, Stan Smith, the qua rtet recorded all of the basic tracks for the disc in a single day (Cox and Smith later overdubbed additional parts to the master tape). Flugge’s medium-tempoed modal work “Yarnek” opens the album, and Cox eases into his first solo by developing a handful of tiny motives, followed by Versace, who takes over with an intense piano improvisation. Meanwhle, Wilson controls the group dynamics from behind his drum kit. Cox’s “Blackjack Blues” is a relaxed piece featuring Versace on organ and wondrously loose interplay in the rhythm section. Cox’s solo does not dazzle the listener with multitudes of notes, but every phrase seems to have deep meaning for him. Near the end, there is an interesting three-way improvisation between Cox (overdubbed on tenor and bass clarinet) and Wilson. Cox switches to alto for Flugge’s Tristano-inspired “Familiarity”. The piece is based on one of Lee Konitz’s favorite songs, “I Remember You” and traces of the legendary saxophonist can be heard in Cox’s solo. Williams gets a solo here as well, and what a treat to hear his deep ringing tones! “Cheryls” adds Smith’s guitar to the ensemble, which opens with an atmospheric introduction and segues into a delicate line for Cox’s soprano. Cox’s “Sunny Rhythm” opens with fragmentary phrases from Cox’s tenor and Versace’ electric piano before settling into an infectious calypso groove. The composer channels Sonny Rollins in his solo before Wilson contributes an inspired solo. “Used to Be” is a grooving Smith composition featuring the unusual pairing of alto flute and Hammond B-3. Cox’s “Adagio”, which started life as a composition exercise, may be the album’s most powerful piece, thanks to the impassioned reading it gets from the quartet. In their hands, it becomes a solemn dirge for beloved souls. Flugge’s “Soirée” lightens the mood with its spirited changes. Cox digs in for his best solo on the date, filled with energy and intriguing ideas. Wilson also scores with a highly melodic drum solo. “Compassion for All” is a gorgeous ballad by Flugge with a tender alto flute countermelody built into the piece. Cox’s tenor solo swirls around the changes after which Williams improvises a remarkable melody of his own. “Mi-Fa-So F’Ornette” is Cox’s tribute to the recently departed Ornette Coleman. The loose swing and open structure help the group recapture the free interplay of Coleman’s ensembles. The album closes with an alternate take of “Cheryls” included to highlight a particularly fine solo by Versace. Cox’s “Compassion” is a follow-up that was worth the wait.

rtet recorded all of the basic tracks for the disc in a single day (Cox and Smith later overdubbed additional parts to the master tape). Flugge’s medium-tempoed modal work “Yarnek” opens the album, and Cox eases into his first solo by developing a handful of tiny motives, followed by Versace, who takes over with an intense piano improvisation. Meanwhle, Wilson controls the group dynamics from behind his drum kit. Cox’s “Blackjack Blues” is a relaxed piece featuring Versace on organ and wondrously loose interplay in the rhythm section. Cox’s solo does not dazzle the listener with multitudes of notes, but every phrase seems to have deep meaning for him. Near the end, there is an interesting three-way improvisation between Cox (overdubbed on tenor and bass clarinet) and Wilson. Cox switches to alto for Flugge’s Tristano-inspired “Familiarity”. The piece is based on one of Lee Konitz’s favorite songs, “I Remember You” and traces of the legendary saxophonist can be heard in Cox’s solo. Williams gets a solo here as well, and what a treat to hear his deep ringing tones! “Cheryls” adds Smith’s guitar to the ensemble, which opens with an atmospheric introduction and segues into a delicate line for Cox’s soprano. Cox’s “Sunny Rhythm” opens with fragmentary phrases from Cox’s tenor and Versace’ electric piano before settling into an infectious calypso groove. The composer channels Sonny Rollins in his solo before Wilson contributes an inspired solo. “Used to Be” is a grooving Smith composition featuring the unusual pairing of alto flute and Hammond B-3. Cox’s “Adagio”, which started life as a composition exercise, may be the album’s most powerful piece, thanks to the impassioned reading it gets from the quartet. In their hands, it becomes a solemn dirge for beloved souls. Flugge’s “Soirée” lightens the mood with its spirited changes. Cox digs in for his best solo on the date, filled with energy and intriguing ideas. Wilson also scores with a highly melodic drum solo. “Compassion for All” is a gorgeous ballad by Flugge with a tender alto flute countermelody built into the piece. Cox’s tenor solo swirls around the changes after which Williams improvises a remarkable melody of his own. “Mi-Fa-So F’Ornette” is Cox’s tribute to the recently departed Ornette Coleman. The loose swing and open structure help the group recapture the free interplay of Coleman’s ensembles. The album closes with an alternate take of “Cheryls” included to highlight a particularly fine solo by Versace. Cox’s “Compassion” is a follow-up that was worth the wait.

EDDIE DANIELS: “HEART OF BRAZIL” (Resonance 1027)

Egberto Gismonti is one of Brazil’s most acclaimed composers. Not a typical samba/bossa nova songwriter, Gismonti’s works encompass the breadth of Brazil’s musical landscape as well as a wide swath of European and American influences. “Heart of Brazil” was recorded to celebrate the composer’s 70th birthday. Eddie Daniels leads a stellar West Coast rhythm section and an outstanding string quartet through an intriguing program which fearlessly embraces this tuneful and challenging music. This tribute album opens with Gismonti’s salute to another great Brazilian composer, Hermeto Pascoal. According to Gismonti, “Lôro” is a piece which allows all of the musicians to improvise and reinvent. Here, Daniels’ clarinet bubbles and Josh Nelson’s piano sparkles over the delightful melody. “Baião Malandro” changes the mood with a stark melody for the strings. Gismonti’s angular melody is a polyrhythmic impression of the rustic Baião region of Northwestern Brazil. Drummer Mauricio Zottarelli has a field day both in h is brief solos and as accompanist, while Daniels navigates his solo around the complex composition. The Harlem Quartet (Ilmar Gavilán and Melissa White, violins; Jamey Amador, viola; and Felix Umansky, cello) deserve special notice for their contributions to this album. They are never mere padding; they have specific and necessary parts to play within the arrangements by Ted Nash, Josh Nelson, Kuno Schmid, and Mike Patterson. On the ballad “Água e Vinho”, the interaction of Daniels’ tenor saxophone and the strings reminds me of “Focus”, a classic Third Stream collaboration between Stan Getz and arranger Eddie Sauter. “Ciranda”, originally part of a symphonic work, offers a different side of Daniels’ tenor sound, one more passionate and imploring. At the beginning of his career, Daniels was primarily known as a tenor man. The clarinet may have eclipsed that in recent years, but it’s good to hear him play tenor again, and in such good form. “Folia” is a complex work which challenges the listener with an ever-changing soundscape featuring a wide range of styles and techniques. The comunication between Daniels and the rhythm section (with Kevin Axt especially active on bass) is a highlight of the album. “Maracatú” is notable for its unique imitation of traditional percussion instruments performed by the instruments of the existing ensemble, rather than on a battery of native drums. Later in the track, Daniels plays a joyously swirling solo on his clarinet, beautifully supported by strings and rhythm. “Adagio” finds Gismonti at his most cosmopolitan, evoking Ravel more than anyone else, while Daniels’ original “Tango Nova” conflates the most famous styles to emerge from Brazil and its neighboring country, Argentina. “Choro” refers a classic form of Brazilian music that has been compared to everything from baroque music to ragtime. Gismonti’s impression utilizes various approaches to rhythm, sometimes appearing in layers. In this performance, the ground beat seems to shift with each bar and Zottarelli does a great job of keeping it all together. “Tango” which veers far from the Argentinean form, is played as a lyric duet between Daniels (clarinet) and Nelson (piano), while “Cigana” is an elegy for a displaced Gypsy woman (the title’s literal translation). “Trem Noturno” is a wild ride aboard an overnight train, with a wide range of tempos and styles. “Auto-Retracto” closes the album with a heartbreaking melody for Daniels’ clarinet. This lovely album is a wonderful introduction to Egberto Gismonti’s music. It is a recording approved by the composer, and that is high praise indeed.

is brief solos and as accompanist, while Daniels navigates his solo around the complex composition. The Harlem Quartet (Ilmar Gavilán and Melissa White, violins; Jamey Amador, viola; and Felix Umansky, cello) deserve special notice for their contributions to this album. They are never mere padding; they have specific and necessary parts to play within the arrangements by Ted Nash, Josh Nelson, Kuno Schmid, and Mike Patterson. On the ballad “Água e Vinho”, the interaction of Daniels’ tenor saxophone and the strings reminds me of “Focus”, a classic Third Stream collaboration between Stan Getz and arranger Eddie Sauter. “Ciranda”, originally part of a symphonic work, offers a different side of Daniels’ tenor sound, one more passionate and imploring. At the beginning of his career, Daniels was primarily known as a tenor man. The clarinet may have eclipsed that in recent years, but it’s good to hear him play tenor again, and in such good form. “Folia” is a complex work which challenges the listener with an ever-changing soundscape featuring a wide range of styles and techniques. The comunication between Daniels and the rhythm section (with Kevin Axt especially active on bass) is a highlight of the album. “Maracatú” is notable for its unique imitation of traditional percussion instruments performed by the instruments of the existing ensemble, rather than on a battery of native drums. Later in the track, Daniels plays a joyously swirling solo on his clarinet, beautifully supported by strings and rhythm. “Adagio” finds Gismonti at his most cosmopolitan, evoking Ravel more than anyone else, while Daniels’ original “Tango Nova” conflates the most famous styles to emerge from Brazil and its neighboring country, Argentina. “Choro” refers a classic form of Brazilian music that has been compared to everything from baroque music to ragtime. Gismonti’s impression utilizes various approaches to rhythm, sometimes appearing in layers. In this performance, the ground beat seems to shift with each bar and Zottarelli does a great job of keeping it all together. “Tango” which veers far from the Argentinean form, is played as a lyric duet between Daniels (clarinet) and Nelson (piano), while “Cigana” is an elegy for a displaced Gypsy woman (the title’s literal translation). “Trem Noturno” is a wild ride aboard an overnight train, with a wide range of tempos and styles. “Auto-Retracto” closes the album with a heartbreaking melody for Daniels’ clarinet. This lovely album is a wonderful introduction to Egberto Gismonti’s music. It is a recording approved by the composer, and that is high praise indeed.

RYAN KEBERLE/FRANK WOESTE: “REVERSO: SWEET RAVEL” (Phonoart 1)

There’s not much talk these days about “jazzing the classics” or its successor, Third Stream Music, but on “Reverso: Suite Ravel”, a unique collaboration between American trombonist Ryan Keberle and German pianist Frank Woeste, the worlds of impressionism and improvisation meet and flourish. The album uses Maurice Ravel’s piano suite “Le Tombeau de Couperin” as a basis for a group of 11 new pieces, six written by Woeste, three by Keberle and the other two collectively improvised. Snippets of the Ravel play into a half-dozen of the movements, but all of the pieces carry the melancholy aura of the original suite. The original piece is transformed into jazz style, but this albu m is not an effort to “update” or “jazz up” Ravel’s work. It is there as a model and a breeding place for melodic ideas. As the movements progress, Ravel’s piece becomes an integral ingredient in the new suite. As with Keberle’s main band, Catharsis, there is a lot of collective improvisation in this quartet. The smooth trombone and mercurial piano of the co-leaders meet in the opening track, “Ostinato”, and Keberle creates countermelodies against the sweeping range of Vincent Courtois’ cello on “Luminism”. On the group improvisation, “Impromptu I”, each member of the group stays out of the other’s way so that individual melodies can emerge. “All Ears” has a martial feel (provided by Jeff Ballard) but the real focus of the track is the two primary voices which interact like parts of a fugue. Courtois plays an emotional pizzicato solo which eventually merges into Keberle’s rhapsodic horn. The dual improvisation gradually builds until Woeste takes over for a piano solo. Then Keberle plays over an expansive background before the quartet plays an oddly scored setting of Ravel’s original fugue. This track segues into “Alangu”, which is a dreamy collective improvisation that seems to exist in slow motion. “Dialogue” pairs Woeste and Coutois in a lyric duet which develops into a passionate cello solo with Courtois playing in his expressive upper range. Coutois introduces Keberle’s “Mother Nature”, a piece fueled by an ostinato which moves from instrument to instrument and changes shape as it does. After another collective improvisation, Woeste’s “Sortilege” pairs a long-phrased cello melody and wild improvisation against a drum pattern which sounds like it exists in a different tempo. Keberle’s “Ancient Theory” incorporates a straight-eighth rock beat and a very slow crescendo that expands over most of the track’s 5-minute duration. Woeste’s “Clair Obscur” completes the suite with a haunting melody that is placed over an animated rhythmic background. The package for this album includes a 1928 quote from Ravel that is still relevant 90 years later: You Americans take jazz too lightly. You seem to see it as a music of little value, vulgar and ephemeral. In my point of view, it is jazz that will give rise to the national music of the United States. This album, created through the auspices of the French American Jazz Exchange Grant, may not completely bring about Ravel’s lofty prediction, but it allows jazz to be treated on the same hallowed ground as Impressionism.

m is not an effort to “update” or “jazz up” Ravel’s work. It is there as a model and a breeding place for melodic ideas. As the movements progress, Ravel’s piece becomes an integral ingredient in the new suite. As with Keberle’s main band, Catharsis, there is a lot of collective improvisation in this quartet. The smooth trombone and mercurial piano of the co-leaders meet in the opening track, “Ostinato”, and Keberle creates countermelodies against the sweeping range of Vincent Courtois’ cello on “Luminism”. On the group improvisation, “Impromptu I”, each member of the group stays out of the other’s way so that individual melodies can emerge. “All Ears” has a martial feel (provided by Jeff Ballard) but the real focus of the track is the two primary voices which interact like parts of a fugue. Courtois plays an emotional pizzicato solo which eventually merges into Keberle’s rhapsodic horn. The dual improvisation gradually builds until Woeste takes over for a piano solo. Then Keberle plays over an expansive background before the quartet plays an oddly scored setting of Ravel’s original fugue. This track segues into “Alangu”, which is a dreamy collective improvisation that seems to exist in slow motion. “Dialogue” pairs Woeste and Coutois in a lyric duet which develops into a passionate cello solo with Courtois playing in his expressive upper range. Coutois introduces Keberle’s “Mother Nature”, a piece fueled by an ostinato which moves from instrument to instrument and changes shape as it does. After another collective improvisation, Woeste’s “Sortilege” pairs a long-phrased cello melody and wild improvisation against a drum pattern which sounds like it exists in a different tempo. Keberle’s “Ancient Theory” incorporates a straight-eighth rock beat and a very slow crescendo that expands over most of the track’s 5-minute duration. Woeste’s “Clair Obscur” completes the suite with a haunting melody that is placed over an animated rhythmic background. The package for this album includes a 1928 quote from Ravel that is still relevant 90 years later: You Americans take jazz too lightly. You seem to see it as a music of little value, vulgar and ephemeral. In my point of view, it is jazz that will give rise to the national music of the United States. This album, created through the auspices of the French American Jazz Exchange Grant, may not completely bring about Ravel’s lofty prediction, but it allows jazz to be treated on the same hallowed ground as Impressionism.

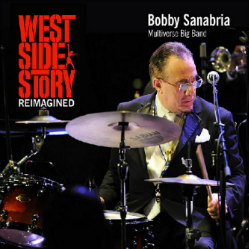

BOBBY SANABRIA: “WEST SIDE STORY REIMAGINED” (Jazzheads 1231)

A few years ago, a Broadway revival of Leonard Bernstein’s “West Side Story” translated some of the original dialogue into Spanish in an effort to equalize the playing field between the Sharks and the Jets. Drummer Bobby Sanabria’s new adaptation of the classic score, “West Side Story Reimagined” builds upon that production with settings that reflect a wide range of Latin rhythms. With arrangements by Jeremy Fletcher, Niko Seibold, Jeff Lederer, Matt Wong, Danny Rivera, Nate Sparks, Eugene Marlow, Andrew Neesley, Takao Heisho and Sanabria himself, the selections retain a great deal of unity without compromising the individual voices of the writers. Brilliantly realized by his Multiverse Big Band, and recorded live at Jazz at Lincoln Center, the score moves back and forth between straight-ahead swing and Latin styles as it instrumentally portrays the gang war between the Caucasians and Puerto Ricans. Trumpeter Max Darché, trombonist Dave Miller and tenor saxophonist Peter Brainin get the first solo opportunities with a blistering chase chorus in “Jet Song” which explodes into tension and a powerful sequence in bomb xicá rhythm, as the Jets encounter t he Sharks. “America” becomes a political football in Lederer’s hands, as he introduces fragments of the national anthems of countries currently opposed by the Trump administration. Lederer incorporates a Venezuelan rhythm called joropo and the solos are performed by trombonist Chris Washburne, alto saxophonist Andrew Gould, pianist Darwin Noguera and electric bassist Leo Traversa. “Gee, Officer Krupke” attempts to update the vaudevillian number into a panorama of New York’s present racial makeup, including Caucasian, Puerto Rican, Cuban, African-Americans and Haitians. Jazzers and rockers also get their segments, with Shareef Clayton’s plunger muted trumpet enlivening the former section. “Tonight” was both a love song and a elaborate quintet in the original show; here, it is played in three different Latin styles—bolero, samba and meringue—with solos by David DeJesus (alto sax), Brainin (tenor), Heisho (cuica) and Noguera (piano). The Gym Scene becomes an elaborate suite here, with a straight-ahead big band swing section for the opening, an Afro-Cuban explosion for the propulsive mambo, and two-part examination of the romantic cha-cha for Tony and Maria’s first dance. The entire saxophone section (DeJesus, Gould, Brainin, Yaacov Mayman and Rivera) exchanges thoughts in the center of the mambo, with Kevin Bryan playing the high trumpet part at the end, and Gabrielle Garo playing flute in the cha-cha. “Maria” receives the most dramatic transformation in the score. The arrangement opens with a series of traditional Yoruba fertility chants. The notes attempt to explain the reasoning, but it seems to be a real stretch. The treatments of the melody are very well played by the ensemble. “Cool” retains Bernstein’s inventive jazz fugue, with DeJesus, Brainin, Clayton and trombonist Tim Sessions all providing solos. Neesley adds an intricate sax soli and a quote of “Drum Boogie” to the mix, and there are occasional nods to hip-hop rhythm. The dramatic action of the rumble is accentuated through a series of Latin rhythm patterns. Mayman, Neesley (trumpet), Matthew Gonzalez (bongo) and Sanabria all perform powerful solos in this section. The love duet “One Hand, One Heart” is set in samba style with DeJesus and Armando Vergara (trombone) portraying the lovers, and Garo returning for another flute solo. “Somewhere” brings us back to the joropo rhythm and introduces electric violinist Ben Sutin as soloist. Fletcher’s setting of the Finale recreates the dramatic action of the musical, but adds a section of collective free improvisation to portray the frustration and sorrow expressed in the denouement. Listeners may have different reactions to this updating of the Bernstein score, but taken on its own terms, it is an exciting and vibrant revamping of an American classic.

he Sharks. “America” becomes a political football in Lederer’s hands, as he introduces fragments of the national anthems of countries currently opposed by the Trump administration. Lederer incorporates a Venezuelan rhythm called joropo and the solos are performed by trombonist Chris Washburne, alto saxophonist Andrew Gould, pianist Darwin Noguera and electric bassist Leo Traversa. “Gee, Officer Krupke” attempts to update the vaudevillian number into a panorama of New York’s present racial makeup, including Caucasian, Puerto Rican, Cuban, African-Americans and Haitians. Jazzers and rockers also get their segments, with Shareef Clayton’s plunger muted trumpet enlivening the former section. “Tonight” was both a love song and a elaborate quintet in the original show; here, it is played in three different Latin styles—bolero, samba and meringue—with solos by David DeJesus (alto sax), Brainin (tenor), Heisho (cuica) and Noguera (piano). The Gym Scene becomes an elaborate suite here, with a straight-ahead big band swing section for the opening, an Afro-Cuban explosion for the propulsive mambo, and two-part examination of the romantic cha-cha for Tony and Maria’s first dance. The entire saxophone section (DeJesus, Gould, Brainin, Yaacov Mayman and Rivera) exchanges thoughts in the center of the mambo, with Kevin Bryan playing the high trumpet part at the end, and Gabrielle Garo playing flute in the cha-cha. “Maria” receives the most dramatic transformation in the score. The arrangement opens with a series of traditional Yoruba fertility chants. The notes attempt to explain the reasoning, but it seems to be a real stretch. The treatments of the melody are very well played by the ensemble. “Cool” retains Bernstein’s inventive jazz fugue, with DeJesus, Brainin, Clayton and trombonist Tim Sessions all providing solos. Neesley adds an intricate sax soli and a quote of “Drum Boogie” to the mix, and there are occasional nods to hip-hop rhythm. The dramatic action of the rumble is accentuated through a series of Latin rhythm patterns. Mayman, Neesley (trumpet), Matthew Gonzalez (bongo) and Sanabria all perform powerful solos in this section. The love duet “One Hand, One Heart” is set in samba style with DeJesus and Armando Vergara (trombone) portraying the lovers, and Garo returning for another flute solo. “Somewhere” brings us back to the joropo rhythm and introduces electric violinist Ben Sutin as soloist. Fletcher’s setting of the Finale recreates the dramatic action of the musical, but adds a section of collective free improvisation to portray the frustration and sorrow expressed in the denouement. Listeners may have different reactions to this updating of the Bernstein score, but taken on its own terms, it is an exciting and vibrant revamping of an American classic.