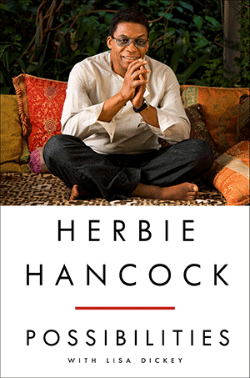

Herbie Hancock is one of the most revered jazz musicians in the world today. In a career spanning five decades, he has created music that is accessible and challenging—usually at the same time. Hancock’s musicality is a constant presence, even when he plays in genres only tangentially related to jazz. Hancock is also someone who most musicians and fans would like to meet. By all accounts, he seems to be a friendly, warm human being without any sort of pretentions. If we can’t all have our own time to hang out with Herbie, at least we have his  recently-published memoir, “Possibilities” (Viking) as a substitute. Lisa Dickey (who is credited as a ghostwriter on Random House’s website) is listed as co-author, and I suspect that she gathered and organized the material, and maintained Hancock’s casual speaking style in the narrative.

recently-published memoir, “Possibilities” (Viking) as a substitute. Lisa Dickey (who is credited as a ghostwriter on Random House’s website) is listed as co-author, and I suspect that she gathered and organized the material, and maintained Hancock’s casual speaking style in the narrative.

Some of the book’s best moments relate to Hancock’s relationship with Miles Davis. Hancock actually opens the book with the famous story of how—during a European concert with Davis—Hancock hit a chord that was way out of the structure, and Davis instinctively played something on his trumpet that made the chord fit into the music. Later, Hancock talks about how he deciphered the cryptic messages Davis would use to instruct the band, and in a humorous aside, Hancock admits that he wasn’t sure if Davis told him to cut “the butter notes” or “the bottom notes”. Hancock’s response was to use sparser voicings (to the point of not using his left hand at all) so no matter Miles really said, the end result was probably what he wanted. Hancock also reveals the primary reason why the quintet’s Plugged Nickel recordings stand out from their other live albums. Apparently, the band was preoccupied with not repeating itself, and Tony Williams proposed that the group play exactly the opposite of what was expected. Significantly, Ron Carter and Wayne Shorter were let in on the plan, but no one told Miles. However, as the recordings show, Davis picked up the challenge rather quickly.

Hancock also tells great stories about the work he issued under his own name. He relates how one of his compositions started as a rhythmic idea written on an airplane napkin which was subsequently lost. Hancock stumbled on the idea again while recording with Davis, and then tried to develop it for an advertising jingle. After attempting to make the tune fit into a standard chord progression, Hancock finally decided to treat the chords as an unresolving cycle. The tune stuck with Hancock after the jingle was submitted, and with a title supplied by his sister Jean, it became the title tune of one of Hancock’s greatest albums: “Maiden Voyage”. Later in the book, he reveals how he created the unique “stereo bass” line that gave “Chameleon” its unique flair. Hancock’s love of electronic instruments and technology is another constant factor in the book, and he tells about his exposure to an early version of an iPad (one not developed by Apple!) and of his early experiences with personal computers and instant messaging

For all of the details he gives about his music, I wish that Hancock would have been more revealing about his private life. Hancock succeeded in ways that other jazz musicians have failed, and I think his insights about those triumphs could help others. For example, consider this story from about halfway through the book: It’s 1975, and Hancock awakes one morning to find a young engineer parked on his doorstep. The young man, Bryan Bell, is completely unknown to Hancock, but after Bell proves his worth by repairing Hancock’s sports car, Hancock says “Listen, you want to stay in my guesthouse a few days?” That’s right—His guesthouse. Now I’m not begrudging Hancock for buying the things he wants, and if a guesthouse is one of those things, so be it. However, since most jazz musicians can’t even afford to own their own home, Hancock must have some method to building his wealth. Obviously part of that wealth came from songs like “Watermelon Man”, a hit side from “Takin’ Off“, the very first album he made as a leader. On the advice of Donald Byrd, he started his own publishing company rather than signing off the rights to Blue Note. Throughout the book, Hancock refers to the ongoing residuals from “Watermelon Man” but did he play the stock market, make investments, or create a special bank account for the royalty payments? Were there options closed to him because he was black? Were there other songs (perhaps “Maiden Voyage” or “Chameleon”) that helped buffer his bank account? The financial outlook for jazz musicians has never been very lucrative, but Hancock has made a better living than most of his contemporaries and I wish he would have shared his secret with the world.

One secret Hancock did let out was his addiction to crack cocaine. Acting against the advice of several friends, Hancock first smoked crack in the late 90s. He tried to resist the drug several times, and even tried to modify the method of smoking it to lessen the drug’s impact. His harrowing narrative recounts the struggles that he had while under the addiction. For years, he did his best to hide his habit from his wife, family and business colleagues, and it took an intervention from them to convince him that he needed help. Until the book came out, few people knew about this chapter of Hancock’s life, and I applaud the courage it took to lose the addiction and live to tell the story. Earlier in the book, Hancock talks about drinking to excess, dropping acid and snorting cocaine. Curiously, he never reveals how he stopped using these substances, nor does he offer any details about the difficulties he had in the process. Without a doubt, crack was the hardest drug for Hancock to kick, but the additional experiences he had with other drugs might have proved to readers that any kind of addiction can be dangerous.

One area where I wish Hancock were a little less detailed is in his lengthy discussions of his Buddhist faith. Hancock states that his faith has made him a better person—and that is probably true—but in the second half of the book, there are references to Buddhism and chanting every few pages. He credits it for winning Grammy awards, finding solutions to musical and personal problems, and even kicking his drug habit. Further, he even recalls trying to force the idea on Miles Davis while the trumpeter was in the hospital! While I appreciate Hancock’s enthusiasm, he should realize that faith is an intensely personal matter, and the effect of his preaching might repel more people from Buddhism that attracting them.

Despite its flaws, Herbie Hancock’s “Possibilities” makes good summer reading. The celebrity references are fun, the storytelling is engaging, and Hancock’s optimistic attitude predominates. Hancock may not have lived as dramatic of a life as Art Pepper, Chet Baker or Miles Davis, but at 75, he is clearly grateful all he has. Considering that Pepper, Baker and Davis never made it to that age, Hancock may have found the ultimate key to success and happiness.