Standing in the shadows of masterworks like “Such Sweet Thunder”, “A Drum Is a Woman” and “Ellington at Newport”, “Ellington Indigos” is a neglected gem from the mid-50s Ducal discography. Unlike the other albums above, “Indigos” was marketed as a commercial album, specifically made for dancing. But Duke Ellington didn’t take orders from the marketing department and while there are no up-tempo numbers on “Indigos”, there are sections of the arrangements that are either out-of-tempo or just too slow for dancing. While the album sold well and received good reviews (including a four-and-a half star rating from Down Beat’s Dom Cerulli), it has been ignored by jazz critics and historians. A pity, since this album contains exceptional performances and settings by classic songs by Ellington and his contemporaries.

Standing in the shadows of masterworks like “Such Sweet Thunder”, “A Drum Is a Woman” and “Ellington at Newport”, “Ellington Indigos” is a neglected gem from the mid-50s Ducal discography. Unlike the other albums above, “Indigos” was marketed as a commercial album, specifically made for dancing. But Duke Ellington didn’t take orders from the marketing department and while there are no up-tempo numbers on “Indigos”, there are sections of the arrangements that are either out-of-tempo or just too slow for dancing. While the album sold well and received good reviews (including a four-and-a half star rating from Down Beat’s Dom Cerulli), it has been ignored by jazz critics and historians. A pity, since this album contains exceptional performances and settings by classic songs by Ellington and his contemporaries.

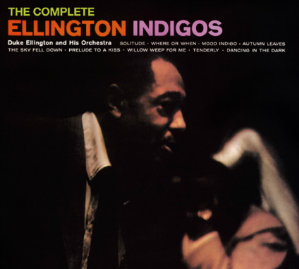

The album has gone through a dizzying series of issues. The original mono edition (Columbia CL-1085) contained nine tracks, while the simultaneously released stereo version (Columbia CS-8053) had eight. Two of the tracks on the stereo LP were different from the mono takes, and the one track that only appeared on the mono LP has been left off of most reissues. Some of those reissues included tracks from the “Indigos” sessions that may not have been intended for inclusion on the original LP. Columbia’s sole CD edition (Columbia CK 44444) is part of the blue-bordered “Columbia Jazz Masterworks” series and only adds to the confusion, jumbling the track order and mislabeling a restored version of “Autumn Leaves” as an alternate take. Several true alternates have emerged and have been occasionally substituted for the master takes. A CD with all of the existing takes was issued on the European Jazz Beat label as “The Complete Ellington Indigos”, but this unauthorized disc may go out-of-print soon in compliance with changing laws regarding public domain recordings on the Continent.

While there is no definitive running order for “Ellington Indigos”, all of the editions open with Ellington’s stunning arrangement of “Solitude”. It is a rare extended feature for Ellington the pianist. He opens alone—quite literally “in his solitude”—with a beautifully-paced rumination on the theme. He moves in and out of tempo as he explores unusual aspects of his 35-year-old theme (the tender single-note melody against his simple stride bass is a highlight). He leads the band in with a strongly marked statement of the theme, and slowly builds the intensity to an impassioned climax. Then suddenly, the band sets up a dramatic piano cadenza, in which Ellington brings the emotional level back down for a quiet contemplative ending. The next track is Richard Rodgers’ “Where or When” set here as a feature for the breathy tenor sax of Paul Gonsalves. There’s a lot of Ben Webster in Gonsalves’ sound, and like his inspiration, Gonsalves adds very little to the melody, letting his romantic delivery tell the story. There is an alternate take of this track, and it offers the album’s first example of Ellington changing the arrangements between takes. The master take opens with a sizzle cymbal roll by Sam Woodyard, while the alternate opens with the horns. The ensemble is a little ragged on the alternate, which makes me suspect that it was recorded before the master. Woodyard’s cymbal delineates the tempo, and the horns respond with a better introduction to Gonsalves’ tenor. (N.B. Terry Teachout tells me that Billy Strayhorn wrote the “Night and Day” arrangement without credit. Makes me wonder if it was Ellington or Strayhorn who added the cymbal roll.—TC)

There are three existing takes of “Mood Indigo” and here Ellington’s changes to the arrangements are even more dramatic. Harold “Shorty” Baker is the featured soloist, and on each take, he improvises in a Harmon mute with bass and drum accompaniment. A stereo alternate starts with the saxes and trombones playing a chorus of the theme before Baker takes over. When Baker ends his solo, Ellington plays a four-bar solo before the band comes in for the final three chords with Baker improvising on top. On the mono master, Ellington plays a four-bar introduction that paraphrases the melody, then goes straight to Baker’s improvisation. The ensemble chorus that had opened the alternate now appears at the end of the arrangement. However, at the bridge, we go back to Baker, bass and drums, followed by the three-chord band tag at the end. The stereo master follows the same basic pattern as the mono master except that this time, the entire ensemble chorus (with one small adjustment) is played at the end so that Baker plays over the band through the bridge and coda. Considering that this was essentially the title track of the album, it is amazing to see Ellington adapting and trimming down his own melody to give his soloist more room.

Taken at a funereal tempo, “Autumn Leaves” features the most atmospheric writing on the album. The original three-chorus arrangement featured Ozzie Bailey singing the original French lyrics in the opening chorus and Johnny Mercer’s English lyrics in the last, with Ray Nance’s violin supplying obbligatos in the outer choruses and a solo in the middle. The French chorus had Bailey accompanied only by Nance and bassist Jimmy Woode, but this lonely and mournful chorus was edited out of the original LP due to time restrictions. The edited version went straight from Ellington’s piano introduction into Nance’s improvisation. Bailey sang a melodic paraphrase on the English chorus, so the only presentation of the original melody on the edited version was played by the band as background, not by the soloists! Bailey was one of Ellington’s better male vocalists (he also played the leading role in the Ellington TV version of “A Drum Is a Woman”), and he conveys the deep emotion of the lyric at the dramatic high-register conclusion of the English chorus. Nance plays extremely well on both the master take and the alternate. Again there are modifications to the arrangement between takes with the alternate featuring an improvised tag by the trumpet section and Ellington playing sharply accented lines behind Nance’s solo (did someone have to ask Duke not to play that way?)

The Ellington’s band’s biggest star, Johnny Hodges, is featured on “Willow Weep for Me” and “Prelude to a Kiss”. “Willow” actually offers more solo time for Baker and Ellington, but Hodges dominates the arrangement with a passionate and bluesy 8-bar solo on both the stereo and mono takes, and an unaccompanied introduction on the stereo take only. “Prelude” is all Hodges and one of his best showcases. Hodges’ swooping entry is framed by an aura of sound from the orchestra (when listening again, check out Duke’s ethereal voicings). Hodges builds his solo slowly, ebbing slightly at the end of the first bridge, then building again to the second bridge with a passionate flurry of notes that approaches the rhythmic (if not harmonic) complexity of bebop. Jimmy Hamilton’s fluid clarinet is featured throughout “Tenderly”. The opening clarinet/piano duet is played rubato, but it leads to a sassy medium-tempo jaunt through this classic song. And while Harry Carney can be heard leading the ensemble backgrounds throughout the album, it is not until the closing “Dancing in the Dark” that his baritone sax is heard in solo. That arrangement expands on “Tenderly” with another spirited medium-tempo episode, this time enhanced with a catchy variation on the melody.

“The Sky Fell Down” was issued only on the mono LP version of “Indigos”. This Ellington piece was known by several names, and recorded under the title “Someone” for Victor in 1942. Both versions featured Nance’s cornet and Hodges’ alto, but despite the attractive melody and chord changes, the soloists found little to do with it on either recording. The Columbia version was recorded in March 1957, and as a result, was probably only recorded in mono. Why Columbia decided to add this track to an already full album is a mystery. But it’s also a mystery why this album has not been re-evaluated over the last 50-plus years. It may have been intended as another way to create an album of Ellington’s greatest hits, but it was clearly an artistic triumph as well. It deserves a definitive—and legitimate—CD edition.