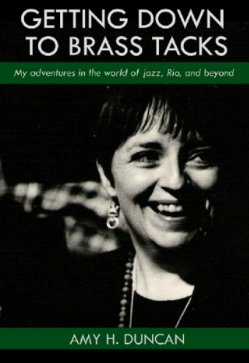

I first met Amy Duncan at the University of Northern Colorado/Greeley Jazz Festival in the early 1980s. At the time, I was living near the campus, building up my musical knowledge and considering a career as a jazz historian. I knew that there were jazz musicians who also wrote about the music, but I had never met one until Duncan arrived in Greeley to review the festival for the Greeley Tribune. We became friends, hanging out both in Greeley and New York City. Several years later, we reconnected on Facebook, and she became one of the staff writers for Jazz History Online. An excerpt from her autobiography “Getting Down To Brass Tacks” became a last-minute substitute for the debut of our Sidetracks column, and while she is not writing for this website at present, she has an open invite to return. When we published the excerpt, the book was only available in electronic formats; it has since been published by Amazon as a standard paperback. While I would ordinarily decline to review the autobiography of a longtime friend, I have made an exception because most of the material in the book describes a very different Amy Duncan than the person I thought I knew.

I first met Amy Duncan at the University of Northern Colorado/Greeley Jazz Festival in the early 1980s. At the time, I was living near the campus, building up my musical knowledge and considering a career as a jazz historian. I knew that there were jazz musicians who also wrote about the music, but I had never met one until Duncan arrived in Greeley to review the festival for the Greeley Tribune. We became friends, hanging out both in Greeley and New York City. Several years later, we reconnected on Facebook, and she became one of the staff writers for Jazz History Online. An excerpt from her autobiography “Getting Down To Brass Tacks” became a last-minute substitute for the debut of our Sidetracks column, and while she is not writing for this website at present, she has an open invite to return. When we published the excerpt, the book was only available in electronic formats; it has since been published by Amazon as a standard paperback. While I would ordinarily decline to review the autobiography of a longtime friend, I have made an exception because most of the material in the book describes a very different Amy Duncan than the person I thought I knew.

Born in New York two days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Duncan spent her early childhood in Cleveland and Long Island. Her family then settled in Newtown, Connecticut (later home of Sandy Hook Elementary), where Duncan remained until moving to Boston for college. Her father was an alcoholic who eventually deserted the family; her mother was strong-willed and found it hard to openly show love for her children. Not surprisingly, young Amy was closest to her older sister, Bertie, and judging from Amy’s narrative, they were inseparable up through their college days (and probably thereafter). While Duncan occasionally steps back to offer her present take on her past activities, most of her story is told from her perspective at the time. Through her vivid descriptions, we understand how she felt around her family, classmates and boyfriends. She offers detailed memories about her earliest exposure to jazz (through a recording from an obscure pianist named Alex Kallao) and her first professional gigs as a pianist and vocalist.

When Duncan went to Boston University in the late 1950s, her life soon became fractured and chaotic. She became pregnant when she was 19 and shortly after, married the first of her four husbands.Two of these marriages, including the first one, were to black men, and the other two were Brazilians. Surprisingly, she makes little mention of the social difficulties of that time for interracial couples and mixed race children. She was highly impulsive, taking extended trips to Mexico and Brazil when her domestic situation seemed out of balance. Developing a passion for macrobiotics and Christian Science, she was able to use her connections within those communities to get her through tough times, but the teachings of those groups sometimes lead her into difficult situations. She drifted in and out of the music scene, and fully admits that she stopped playing and listening to music for years at a time.

Her life seemed to stabilize when she became a jazz and features writer for the Christian Science Monitor. She interviewed a wide range of musicians including Miles Davis and Gerry Mulligan, moved from Boston to New York City, and performed with a wide range of groups. After writing about Toshiko Akiyoshi for the Monitor, she became Akiyoshi’s personal assistant and was the road manager for a Japanese tour by the Akiyoshi/Tabackin big band. Her connection to the Greeley jazz scene also happened during this time, and a performance by UNC’s Trombone & Euphonium Jazz Ensemble inspired her to start her own brass-and-rhythm group, Brass Tacks. The first edition of that group started in New York, but Duncan was unable to secure steady bookings for the ten-piece band. She created a new edition of the group when she made a permanent move to Rio in the 2000s.

Duncan’s first trips to Rio de Janeiro came through story suggestions she made to her editor at the Monitor. She quickly developed a love for the Brazilian city, but it took a few years and a couple more failed marriages before she settled there alone. Her passion for the samba, Carnaval, and the relaxed Brazilian lifestyle enlivens the final chapters of the book. With loving detail, she tells about the various samba schools, the instrumental makeup of the bands, and the excitement of marching in a Carnaval parade. She relates how she adapted from a time-conscious New Yorker to a laid-back Brazilian transplant, and discusses the way Brazilians deal with unpleasant living conditions through an attitude called jeitinho.

Duncan refrains from making grand conclusions about her life. Instead, she simply tells her story through her own viewpoint and lets the readers make their own judgments. I can’t say that I agree with all of her life decisions, but I admire the way she has bounced back from adversity. Amy Duncan’s story might be a long way from Horatio Alger’s, but she emerges as a survivor who has found inner peace and strength from the troubles and triumphs of her life.

Good work, my friend.