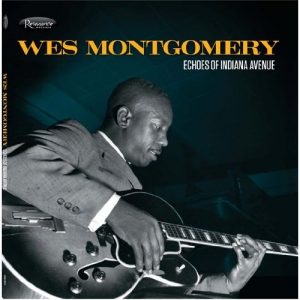

It is said that a jazz musician lives on through his recordings. When previously unissued recordings turn up years after a musician’s death, it seems to belie that musician’s demise, as if the musician is hiding somewhere in the world, turning out new recordings. The legacies of artists like John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Charlie Parker and the British tenor saxophonist Tubby Hayes have been immeasurably heightened through posthumous releases. However, not all past jazz giants left tons of hidden recorded treasures. Resonance’s new Wes Montgomery release “Echoes of Indiana Avenue” represents the first full album of unreleased Montgomery in the past 25 years.

It is said that a jazz musician lives on through his recordings. When previously unissued recordings turn up years after a musician’s death, it seems to belie that musician’s demise, as if the musician is hiding somewhere in the world, turning out new recordings. The legacies of artists like John Coltrane, Bill Evans, Charlie Parker and the British tenor saxophonist Tubby Hayes have been immeasurably heightened through posthumous releases. However, not all past jazz giants left tons of hidden recorded treasures. Resonance’s new Wes Montgomery release “Echoes of Indiana Avenue” represents the first full album of unreleased Montgomery in the past 25 years.

Of course, Montgomery had his own unique sound. He stopped using guitar picks because he could practice late at night using his thumb as a plectrum and not wake up his wife and children. He never learned to read music, but he had a phenomenal ear that allowed him to discern melodic paths through complex chord changes. When these tapes were made (around 1957–1958), Montgomery was still a local musician in Indianapolis, playing late-night gigs after working at non-music jobs during the day.

The recordings, which first turned up on ebay a few years ago, survived without notations of recording dates, personnel or even the reason for their existence. Producers Michael Cuscuna, Zev Feldman and George Klabin (along with several Indiana jazz experts) have made educated guesses of the identities of most of the accompanying musicians, and have pieced together a logical hypothesis of their meaning. Whatever information crops up about these recordings in the coming months and years, there is no doubt that they offer us a rare glimpse of Montgomery as a developing artist.

On the opening track, Shorty Rogers’ “Diablo’s Dance”, the lines of Montgomery’s solo sound like his eventual solo voice, but the rich sound is not there yet, with notes that don’t speak and a general flatness of the sound. His tone is better on “Round Midnight” and the change in sound quality and Montgomery’s soulful improvisation makes me think that this track was recorded much later than “Diablo”. On the version of “Straight, No Chaser”, Wes is joined by his brothers Buddy on piano and Monk on bass. Wes’ tone is flat and unfocused again, but his ideas are excellent and he creates a fine solo. We also hear some of his block chords as he accompanies his brothers. There is a spirited chase between Buddy and Wes, with touches of guitar octaves before the track fades out. “Nica’s Dream” has the same backup as “Diablo”, and thus the guitar sound lags behind the quality of the musical invention. “Darn That Dream”, which like “Round Midnight” pairs Montgomery with organist Melvin Rhyne, is a restrained but lovely version of the Jimmy Van Heusen standard, with Montgomery playing a catchy ostinato behind the organ solo, and offering a brief and touching improvisation before returning to the melody.

“Take The A Train” was recorded in a nightclub, and from the guitar sound, I would guess that it was recorded between the “Diablo” and “Round Midnight” sessions. This track gives us our first glimpse of Montgomery’s building-block method of creating a solo—single lines to octaves to block chords—albeit, here it occurs within a group of four-bar exchanges, and the three tiers do not receive equal space. The version of “Misty” that follows is also claimed to be live, but again the sound quality and depth of Montgomery’s tone makes me suspect a later date. Wes’ solo is a beauty, based on a recurring triplet figure and loaded with expertly-sculpted melodies. “Body & Soul” (probably part of a ballad medley, as pianist Earl van Riper segues into “Don’t Blame Me” at the end of Montgomery’s solo) features another fine Montgomery solo, created entirely from single lines and only occasional hints of the tone issues that marred the earlier sessions.

The final cut, the live “After Hours Blues” is a true curiosity. It sounds as if Montgomery borrowed a solid-body guitar for this tune and the group decided to fool around by playing a gritty Chicago-style electric blues. There is plenty of good-natured laughter in the background as Montgomery plays in a style almost entirely foreign to his usual approach. I doubt there’s anything quite like it anywhere in Montgomery’s discography.

The sound jumps from mono to stereo throughout, and as I’ve noted, the music appears to have come from several sessions. This is potentially good news for Montgomery fans, as the possibility exists for additional recordings to emerge from these sessions. For now, we can be grateful that Resonance has issued this important historical recording, complete with excellent sound restoration and a generous booklet of informative liner notes. The album is available on CD and limited-edition LP, and is an essential addition to any classic jazz collection. May the legacy of Wes Montgomery continue!