In the mid-to-late 1970s, the jazz scene was dominated by jazz-rock

fusion. While hampered by the absence of Miles Davis—whom many feared had permanently retired—musicians like Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Michael Brecker, Wayne Shorter, Joe Zawinul, and Jaco Pastorius continued to create viable music in the style. Meanwhile, in the Berklee classrooms in Boston, young musicians like Joe Lovano, John Scofield, and Kenny Werner were studying ECM-inspired music and advanced jazz compositions with professors Gary Burton and Steve Swallow. Presenting less of a shadow than they had in earlier years were jazz icons such as Dizzy Gillespie, Stan Getz, Milt Jackson, and Oscar Peterson, who continued to play their established styles, and, on occasion, took chances with other genres. One of the main reasons that these veterans were still working was that jazz audiences had never abandoned bebop. A reissue boom, inaugurated with “The Smithsonian Collection of Classic Jazz”, and augmented with easily-obtainable albums from Smithsonian, Fantasy, and Columbia, helped to rebuild the audience for straight-ahead jazz.

Jazz had evolved considerably since the nights when Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Bud Powell reigned on 52nd Street, and in 1976, when Dexter Gordon made a triumphal return to the US after a long residency in Europe, the music he played reflected the greater harmonic and rhythmic freedoms of 1960s progressive jazz. Phil Woods was another former expatriate, and he expanded his combo’s repertoire with a broad collection of under-recorded works from jazz composers including Neal Hefti, Sam Rivers, and Wayne Shorter. Meanwhile, Woods’ protégé, Richie Cole, barnstormed across the US with vocalese master Eddie Jefferson, thrilling young audiences with a mix of classic lyricized jazz standards and hyper-tempo romps through tunes ranging from “Harold’s House of Jazz” to the theme song from “I Love Lucy”.

Two other survivors, neither as well-known as the musicians above, were also part of the classic jazz scene. Both had played with Charlie Parker during his final years. Both had ignored Parker’s advice and became heroin addicts—and successfully beat the habit. In the spring of 1980, these two musicians, Red Rodney and Ira Sullivan formed a new quintet with a young, energetic rhythm section, performing a repertoire that embraced contemporary jazz styles from a strong bebop foundation. Detailed discussions of the seven commercial albums and six astounding concert broadcasts by this group will form the majority of this historical essay, but the story of the Rodney/Sullivan collaborations actually began a quarter-century earlier in the city of Chicago.

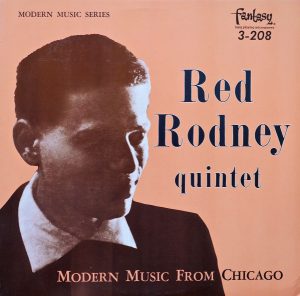

At the 1980 Chicago Jazz Festival, Red Rodney quipped, “Twenty-five years ago, I passed through Chicago…and I stayed two years!” After finishing his tenure in Parker’s quintet, Rodney spent a few years in his native Philadelphia, where he created successful business booking orchestras for bar mitzvahs and weddings. While he made a lot of money, he missed playing jazz, so he sold the business and headed west. When he landed a gig at Chicago’s Bee Hive, he was reunited with Ira Sullivan, whom he had met on a job with Charlie Ventura. Sullivan was a legend in the making, self-taught, and equally proficient on trumpet and saxophones. Together, Rodney and Sullivan led the house band at the Bee Hive with the outstanding rhythm section of pianist Norman Simmons, bassist Victor Sproles, and drummer Wilbur Campbell. In June 1955, Fantasy Records invited the Rodney/Sullivan group (with Roy Haynes subbing for Campbell) into Universal Studios to record the album “Modern Music from Chicago”.

The Rodney/Sullivan LP was part of a series of records that also highlighted jazz from San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Indiana University. The Chicago album was the standout, primarily for the outstanding chemistry of the band and the dynamic partnership of Rodney and Sullivan. The album was “radio-friendly” in every sense of the word: the tracks were compact, running between three and six minutes, and three of the original compositions were titled for prominent disc jockeys in Chicago and Cincinnati. Simmons wrote five of the originals, and arranged all of the others, save Sullivan’s “Hail to Dale” and the head arrangement of “Rhythm in a Riff”. While the music is reflective of its time, it is in no way dated, a quality that can be attributed to the concise solos and supportive charts. “Taking a Chance on Love” opens with an extremely catchy introduction by the horns and rhythm. Rodney continues with a fine variation on Vernon Duke’s melody. A return to the opening riff brings on Sullivan’s lithely swinging tenor, followed by Rodney’s bravura trumpet. When the arrangement interrupts his statement, Rodney uses the riff to bolster his solo. Simmons plays a spritely half-chorus and the track ends with another ensemble variation on the melody. “Dig This” is a bright bop line on the changes of “Indiana” with outstanding solos by the horns and snappy asides from Haynes’ snare. “Red is Blue” is a slow, exotic walk through the harmony of “Woody’n You” highlighted by a fine melodic solo from Sproles, while “Clap Hands! Here Comes Charlie” puts Haynes into the solo spotlight for a thrilling feature. Then the group increases the excitement as Sullivan grabs his trumpet and engages Rodney in a duel for “On Mike” (referred to as “Trumpet Juice” in Joe Segal’s liner notes). The trumpet styles of Rodney and Sullivan were quite similar in 1955, as both young men seemed eager for battle. Simmons’ chart builds in breaks and riffs for both horns, and the solo sequence is an elaborate chase with the momentum growing in each chorus. Simmons squeezes in 8-bar solos before each trumpeter plays an encore chorus. Just like Roger Bannister’s mile run, this wild trumpet chase is completed in just 4 minutes. On the first side’s closer, “The Song is You”, the rhythm section is slightly out of sync but Rodney’s solo overflows with great melodic warmth.

The Rodney/Sullivan LP was part of a series of records that also highlighted jazz from San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Indiana University. The Chicago album was the standout, primarily for the outstanding chemistry of the band and the dynamic partnership of Rodney and Sullivan. The album was “radio-friendly” in every sense of the word: the tracks were compact, running between three and six minutes, and three of the original compositions were titled for prominent disc jockeys in Chicago and Cincinnati. Simmons wrote five of the originals, and arranged all of the others, save Sullivan’s “Hail to Dale” and the head arrangement of “Rhythm in a Riff”. While the music is reflective of its time, it is in no way dated, a quality that can be attributed to the concise solos and supportive charts. “Taking a Chance on Love” opens with an extremely catchy introduction by the horns and rhythm. Rodney continues with a fine variation on Vernon Duke’s melody. A return to the opening riff brings on Sullivan’s lithely swinging tenor, followed by Rodney’s bravura trumpet. When the arrangement interrupts his statement, Rodney uses the riff to bolster his solo. Simmons plays a spritely half-chorus and the track ends with another ensemble variation on the melody. “Dig This” is a bright bop line on the changes of “Indiana” with outstanding solos by the horns and snappy asides from Haynes’ snare. “Red is Blue” is a slow, exotic walk through the harmony of “Woody’n You” highlighted by a fine melodic solo from Sproles, while “Clap Hands! Here Comes Charlie” puts Haynes into the solo spotlight for a thrilling feature. Then the group increases the excitement as Sullivan grabs his trumpet and engages Rodney in a duel for “On Mike” (referred to as “Trumpet Juice” in Joe Segal’s liner notes). The trumpet styles of Rodney and Sullivan were quite similar in 1955, as both young men seemed eager for battle. Simmons’ chart builds in breaks and riffs for both horns, and the solo sequence is an elaborate chase with the momentum growing in each chorus. Simmons squeezes in 8-bar solos before each trumpeter plays an encore chorus. Just like Roger Bannister’s mile run, this wild trumpet chase is completed in just 4 minutes. On the first side’s closer, “The Song is You”, the rhythm section is slightly out of sync but Rodney’s solo overflows with great melodic warmth.

Side 2 opens with a medium swing version of “You and the Night and the Music”, again highlighted by Simmons’ written melodic variations. Simmons also contributes a soulful chorus played on an out-of-tune piano. Rodney follows with a rich, warm invention, and Sullivan offers an edgy contrast in his 8-bar solo. “Laura” is another Rodney feature, this one in a slow ballad tempo with a Harmon mute highlighting his thoughtful lines. Sullivan echoes Sonny Rollins on the boppish “Hail to Dale”, with Rodney playing at his most agitated level in both his solo and in exchanges with Haynes. “Jeffie” has an attractive stop-time figure built into the accompaniment and another catchy melody. Sullivan sounds as if he was continuing his solo from the previous track, albeit at a quicker tempo, and Rodney’s warm tone and ideas return in his solo here. “Rhythm in a Riff” was a blues Billy Eckstine used to sing with his bebop big band. The Rodney/Sullivan version starts as an instrumental, but in the second chorus, Rodney surprises us by singing the tune, complete with scatted asides. He even plays his trumpet on the brief instrumental exclamations (all done in real-time—it doesn’t sound like the tape was edited or overdubbed). This thoroughly delightful album concludes with the medium-up tempo blues, “Daddy-O”, featuring another outstanding series of solos by Sullivan, Rodney, Simmons, and Haynes, in that order. The album was out-of-print for many years until Fantasy included it in their Original Jazz Classics series. It is hardly coincidental that the long-awaited reissue occurred in 1983, as Red and Ira’s quintet was at its peak popularity.

Sullivan reaped the greatest benefits from the Fantasy album. In three sessions spread out over 1956, he recorded the LP “The Billy Taylor Trio Introduces Ira Sullivan” for ABC-Paramount, where he was featured on trumpet, alto, and tenor saxes. In addition, he introduced himself to his new listeners in a brief, but well-written liner essay which told of his musical self-education and his goals. In June, Sullivan began a seven-month tenure with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers. His only recordings with Blakey were unissued at the time, but were eventually released as CD bonus tracks for the Columbia album, “Drum Suite”. We don’t have details about Sullivan’s tours with Blakey, but the discographies reveal a very hectic recording schedule. He was back in Chicago in early September to record a disc for Argo, “Chicago Scene”, and returned to the Apple in late October for a Blue Note date led by tenor saxophonist J.R. Monterose. Then he was home again in November to record the majority of the album with Taylor. The incessant traveling was all the more difficult because there was a newborn at home, and Ira longed to spend time with his wife and baby girl. After leaving Blakey in early 1957, Sullivan swore he’d never tour to the same extant again. Years later, he would remind himself of that pledge.

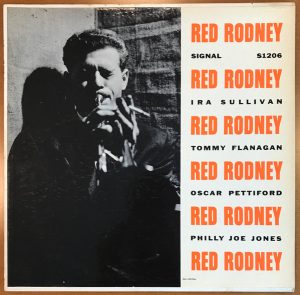

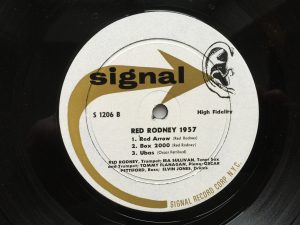

While Sullivan’s life and career surged, Red Rodney was in jail on drug-related charges. When he was released, he played in Las Vegas behind Sammy Davis, Jr. before returning to jazz with another album. “Red Rodney: 1957” was issued on Signal Records, and the album featured a  familiar front line—Red Rodney and Ira Sullivan—with an outstanding rhythm section. Pianist Tommy Flanagan and drummer Elvin Jones were both new arrivals from Detroit (but contrary to some reports, the Rodney/Sullivan dates were not their first recordings in New York), while bassist Oscar Pettiford and drummer Philly Joe Jones (who played on the LPs first side, replaced by Elvin on the flip side) were long-standing bop veterans. Rodney’s original melody, “The Red Arrow”, is the basis for the album’s celebrated trumpet duet. For once, the title was not a pun on Rodney’s name; producer Don Schlitten said he named it after the arrow that appeared on the original

familiar front line—Red Rodney and Ira Sullivan—with an outstanding rhythm section. Pianist Tommy Flanagan and drummer Elvin Jones were both new arrivals from Detroit (but contrary to some reports, the Rodney/Sullivan dates were not their first recordings in New York), while bassist Oscar Pettiford and drummer Philly Joe Jones (who played on the LPs first side, replaced by Elvin on the flip side) were long-standing bop veterans. Rodney’s original melody, “The Red Arrow”, is the basis for the album’s celebrated trumpet duet. For once, the title was not a pun on Rodney’s name; producer Don Schlitten said he named it after the arrow that appeared on the original record label. More important than the title was the tune itself. As Ira Gitler wrote in the Onyx LP reissue (re-titled for this song), the opening section of the theme turns up in Rodney’s “Star Eyes” solo, and there’s a paraphrase of it in his solo on “Ubas”. As “Star Eyes” was recorded on the first session (November 22) and “Red Arrow” and “Ubas” come from the second (November 24), just when was the melody for “Red Arrow” committed to paper? Rodney could have improvised the riff out of thin air on “Star Eyes” and developed the tune before the next session, or he could have quoted something he had written days or weeks before.

record label. More important than the title was the tune itself. As Ira Gitler wrote in the Onyx LP reissue (re-titled for this song), the opening section of the theme turns up in Rodney’s “Star Eyes” solo, and there’s a paraphrase of it in his solo on “Ubas”. As “Star Eyes” was recorded on the first session (November 22) and “Red Arrow” and “Ubas” come from the second (November 24), just when was the melody for “Red Arrow” committed to paper? Rodney could have improvised the riff out of thin air on “Star Eyes” and developed the tune before the next session, or he could have quoted something he had written days or weeks before.

“Star Eyes” is the album opener, with Rodney playing the melody supported by Sullivan’s tenor sax. The “Red Arrow” quote appears in languid form at the top of Rodney’s second chorus, and by that point in the album, it is already obvious that the time behind bars had dimmed the trumpeter’s exuberant tone and brilliant technique. On the other hand, Sullivan’s tenor is noticeably better than before, with the Rollins influence becoming a greater part of his tone and concept. Flanagan’s solo is as tasty as anything he played in the years ahead, and Pettiford’s golden tone rings out during his superb melodic solo. Rodney’s ballad style had improved since the Fantasy album, as demonstrated in his gorgeous reading of “You Better Go Now”, a song usually associated with pianist/vocalist Jeri Southern. Sullivan creates a soulful variation on the tune in his spot, followed by tender improvisations by Flanagan and Pettiford before Rodney’s final chorus and cadenza. A bright-tempoed “Stella by Starlight” closes the first side. Philly Joe Jones, restrained on the previous tracks, finally lets loose and cooks behind the soloists. Sullivan’s solo is certainly helped by the interaction, and Rodney taps into his energy reserve for a very lively solo. Flanagan digs into the groove before yielding to Jones, whose brief solo leads the horns in for the collectively improvised final chorus, and Rodney’s rubato cadenza. “The Red Arrow” trumpet duel leads off the second side, with Rodney leading off the solos. The chase sequence is less complex than on Fantasy’s “Trumpet Juice”/“On Mike”, but the brief piano interludes are retained to separate the trumpet solos. “Box 2000” is a long-limned blues melody by Rodney. Again, Sullivan’s tenor technique is astounding, and it’s rather surprising that he did not become known as one of jazz’s finest straight-ahead players. Rodney’s embouchure gives him more trouble, and both Flanagan and Pettiford get short solos before a round-robin of exchanges commences with Elvin Jones. Not yet the powerhouse he would become with John Coltrane, Elvin plays an impressive set of four-bar thoughts against the two horns. The album concludes with “Ubas”, a spicy up-tempo Latin tribute to conga master Sabu Martinez. Jones sets up a burning rhythm that inspires excellent solos from the group.

At this point, it becomes much more difficult to trace Rodney’s activities. The trumpeter was an engaging storyteller, if not always a truthful one. The facts behind the “Albino Red” story, memorably recreated in the movie “Bird”, have been questioned in recent years, even though it sounds like a crazy scheme Charlie Parker might try to endure a tour of the Deep South. In his book, “Riding on a Blue Note”, jazz and film historian Gary Giddins related an even more insane Rodney con job, with the trumpeter impersonating a real-life general, cashing fraudulent paychecks in his name, and eventually attempting to heist a $180,000 payroll from the Atomic Energy Commission! The story is hilarious (and it’s worth finding the book to read the story in its entirety) but was it true? I’m sure that Giddins fact-checked Rodney’s tale on his own before publishing the article, but years later, a potential Rodney biographer was unable to verify the AEC story. It’s entirely possible that Rodney made up the tale from whole cloth, but even if we accept the basic story, Giddins’ dates are clearly askew: he places the tale in 1958, but we know that Rodney made recordings with Tony Scott in New York on August 8 of that year, and in Philadelphia under his own name in February 1959. Does it make sense that someone planning and/or executing an elaborate con job in Nevada would suddenly fly cross-country to do a one-shot recording session in New York, and then a few months later, take a greater risk of discovery by scheduling a two-day session in his hometown? Giddins also states that at the same time, trombonist J.J. Johnson wrote the liner notes for a Verve anthology of Charlie Parker sides. When Johnson got to the Parker/Rodney track “Swedish Schnapps”, he wrote “By the way, whatever happened to Red Rodney?” That album was not produced until 1966, by which time Rodney was back in jail.

Somehow, Ira Sullivan never served time for his narcotics addiction. He returned home to Chicago, where he worked in nightclubs and recorded as a sideman and leader. His Delmark album “Blue Stroll” features a remarkable track called “Bluzinbee” where Sullivan improvises on all of his primary instruments and one minor addition (trumpet, alto sax, tenor sax, baritone sax, and E-flat alto horn, aka “peck horn”). He also appeared alongside another great multi-instrumentalist on the album “Introducing Roland Kirk”, on which Sullivan wisely stuck to trumpet and tenor sax, with specific indications of when it was Sullivan and not Kirk on tenor! In 1962, his Chicago Jazz Quintet played extensively in a legendary tribute concert to Charlie Parker. By this time, Sullivan’s heroin dependence was getting worse. He made a trip to Florida to see his parents and while there, discovered that the Sunshine State had a suitable atmosphere for kicking bad habits. Jerry Coker—who had played on Fantasy’s “Modern Music from Indiana University” album many years before—had also relocated to Miami where he was involved with the Frost School of Music. Coker invited Sullivan to join the faculty, even though the self-taught saxophonist considered himself unqualified for the job. When Sullivan entered the classroom, he soon discovered that he could teach the students how to listen with great intensity and how to react to the music being created around them. Sullivan single-handedly created a jazz scene in Miami and worked with the most talented of his Frost students, including Pat Metheny and Jaco Pastorius. At the same time, he started to explore progressive jazz, and soon became proficient in that style.

Red Rodney certainly noticed the denigration of his chops after his first prison sentence, and from then on, he arranged to practice trumpet during incarcerations. He played in Vegas backup bands when he was released, and picked up jazz gigs when he could. Unfortunately,  Rodney’s teeth were in very bad shape, and his restructured technique did not solve all of the problems that his dental problems created. Adding to his medical issues, Rodney was temporarily paralyzed after suffering a stroke while playing an engagement at Dante’s in Los Angeles. It was not until the late 1970s during a stay at the penitentiary in Lexington, Kentucky that he had the surgery which allowed him to get a complete set of dental implants. Lexington also had an excellent music program at the local university which gave Rodney the chance to coach and inspire young musicians. In one case, he didn’t have to leave the prison: a young rock guitarist named Wayne Kramer was also doing time. Rodney took the young man under his wing and became his mentor. Rodney’s recording career resumed with a 1973 Parker tribute on Muse “Bird Lives”; by 1979, he had recorded with Dexter Gordon, Bill Watrous, Sam Noto and Richie Cole. After hearing a progressive tune composed by Jack Walrath, he asked the trumpeter to write a group of songs he could use in his own group.

Rodney’s teeth were in very bad shape, and his restructured technique did not solve all of the problems that his dental problems created. Adding to his medical issues, Rodney was temporarily paralyzed after suffering a stroke while playing an engagement at Dante’s in Los Angeles. It was not until the late 1970s during a stay at the penitentiary in Lexington, Kentucky that he had the surgery which allowed him to get a complete set of dental implants. Lexington also had an excellent music program at the local university which gave Rodney the chance to coach and inspire young musicians. In one case, he didn’t have to leave the prison: a young rock guitarist named Wayne Kramer was also doing time. Rodney took the young man under his wing and became his mentor. Rodney’s recording career resumed with a 1973 Parker tribute on Muse “Bird Lives”; by 1979, he had recorded with Dexter Gordon, Bill Watrous, Sam Noto and Richie Cole. After hearing a progressive tune composed by Jack Walrath, he asked the trumpeter to write a group of songs he could use in his own group.

The combo which eventually became the Red Rodney/Ira Sullivan Quintet started in 1979 in Manhattan Plaza, a famous apartment complex in Hell’s Kitchen which—then and now—offered luxury apartments at reduced rates for performing artists. Pianist Garry Dial (who was also in that composition class at Berklee) was a resident at the Plaza, as was Walrath. Dial had met Rodney through a mutual friend, and Rodney was impressed enough to hire Dial for a three-month hotel gig. At the time, Rodney was living in a halfway house and he had to follow a strict 7 pm curfew. Afternoon rehearsals at Dial’s apartment were no problem, of course, so Rodney connected with tenor saxophonist Billy Mitchell to rehearse the newly arrived compositions by Walrath. Mitchell opted not to tour with the band, so in February 1980, Rodney and Dial traveled to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to play a quartet gig at Bubba’s jazz club. Sullivan was there, and the two friends reunited after 23 years. After Ira sat in, Red invited him to come up to New York to assemble and co-lead a quintet. Sullivan moved in with Dial, and in the first months of the quintet, the two men rehearsed and developed tunes before and after the gig.

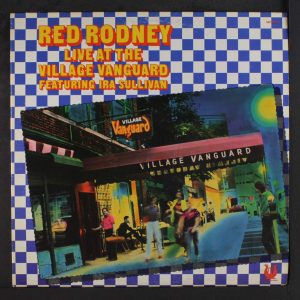

The quintet’s first engagement was set at the Village Vanguard on May 8 and 9, 1980, and Malcolm Addey was there to record the performances for Muse Records. Rodney was already under contract to Muse, and within a year, Sullivan followed suit. However, at the same time, the ex-Columbia music executive Bruce Lundvall was scouting talent for his new label, Elektra-Musician. He subsequently signed the Rodney/Sullivan Quintet. This meant that recordings by the same ensemble appeared in three different guises on two separate labels. The original Village Vanguard recordings (which included a supplemental live date on July 5) were issued by “Red Rodney featuring Ira Sullivan”. 1981 studio recordings by the band on Muse featured the artist credits of “Red Rodney with Ira Sullivan” or Ira Sullivan with Rodney’s name presented with the other group members on the front cover. The recordings on Elektra-Musician were by the “Red Rodney & Ira Sullivan Quintet”. And just to make things a little more tangled, Joe Fields of Muse issued the three volumes from the Vanguard in sporadic fashion, the first in 1980, the second in 1984, and the last in 1986. By the time the final volume of their debut live session was issued by Muse, the group had already broken up! To minimize confusion, this essay will discuss the Vanguard sessions as a single unit, ignoring the delayed releases of the last two volumes.

“Live at the Village Vanguard” opens with Walrath’s stunning “Lodgellian Mode”, and the shock is palpable. The tune starts with a strongly played modal vamp with Sullivan on soprano sax, followed by Dial with a McCoy Tyner-influenced statement. If the listener suspects that the wrong LP was placed in the cover, the unmistakable exuberance of Rodney’s trumpet indicates that this is indeed the proper record. Sullivan displays his unique distillation of Coltrane’s style in his solo. Walrath’s tune alternates between bebop and modal, and that exchange of intensity became a trademark of the Rodney/Sullivan quintet. Bill Evans was in the audience on the first night of the band’s Vanguard engagement, and Dial said he was a little intimidated when the band played a favorite Evans vehicle, “A Time for Love”. No need for worry—the Rodney/Sullivan version is a beauty, with Rodney’s Harmon muted trumpet set against Sullivan’s open flugelhorn, over velvet-cushioned rhythm. Another young composer who contributed to the Rodney/Sullivan band book was drummer Jeff Meyer. His piece, “Mr. Oliver” melds bop, modality, and chromaticism in a gentle medium tempo groove. As with many recordings of this quintet, the veteran horn men show their bebop credentials in the structure and melodic nature of their improvisations, yet they are completely committed to the contemporary style. Simon Salz’s moody “What Can We Do?” builds from a rich-toned bass ostinato played by Paul Berner to a lovely harmonized melody for the flugelhorns of Rodney and Sullivan. Drummer Tom Whaley builds intensity with his cymbals under Sullivan’s lyric solo, and then follows the roller-coaster variations in Rodney’s improvisation. Sullivan switches to soprano for an impassioned solo, and Whaley’s accents become more and more prominent. Dial offers a contrast with a solo featuring plenty of space around the improvised melody. “Come Home to Red” and “Blues in the Guts” are both by Walrath, the first being a ballad feature for Rodney with starkly different obbligati emerging simultaneously from Sullivan’s flute and Berner’s bass. Sullivan’s solo builds to a dramatic climax, and Rodney’s powerful solo brings the piece to a close over an unexpected Latin vamp. “Guts” is an elaborate study of the blues with vamp interludes leading to a blowing chorus that jumps between the related keys of B-flat and E-flat. Rodney flies through his solo, eagerly taking on all of the challenges; Sullivan imitates Rodney’s exuberant high-register wails at the top of his chorus but continues with more concentration on note choices. Then the two trumpeters give us the trumpet chase we’ve anticipated all along. It is short but thrilling, and completely within the progressive style.

“Lodgellian Mode”, and the shock is palpable. The tune starts with a strongly played modal vamp with Sullivan on soprano sax, followed by Dial with a McCoy Tyner-influenced statement. If the listener suspects that the wrong LP was placed in the cover, the unmistakable exuberance of Rodney’s trumpet indicates that this is indeed the proper record. Sullivan displays his unique distillation of Coltrane’s style in his solo. Walrath’s tune alternates between bebop and modal, and that exchange of intensity became a trademark of the Rodney/Sullivan quintet. Bill Evans was in the audience on the first night of the band’s Vanguard engagement, and Dial said he was a little intimidated when the band played a favorite Evans vehicle, “A Time for Love”. No need for worry—the Rodney/Sullivan version is a beauty, with Rodney’s Harmon muted trumpet set against Sullivan’s open flugelhorn, over velvet-cushioned rhythm. Another young composer who contributed to the Rodney/Sullivan band book was drummer Jeff Meyer. His piece, “Mr. Oliver” melds bop, modality, and chromaticism in a gentle medium tempo groove. As with many recordings of this quintet, the veteran horn men show their bebop credentials in the structure and melodic nature of their improvisations, yet they are completely committed to the contemporary style. Simon Salz’s moody “What Can We Do?” builds from a rich-toned bass ostinato played by Paul Berner to a lovely harmonized melody for the flugelhorns of Rodney and Sullivan. Drummer Tom Whaley builds intensity with his cymbals under Sullivan’s lyric solo, and then follows the roller-coaster variations in Rodney’s improvisation. Sullivan switches to soprano for an impassioned solo, and Whaley’s accents become more and more prominent. Dial offers a contrast with a solo featuring plenty of space around the improvised melody. “Come Home to Red” and “Blues in the Guts” are both by Walrath, the first being a ballad feature for Rodney with starkly different obbligati emerging simultaneously from Sullivan’s flute and Berner’s bass. Sullivan’s solo builds to a dramatic climax, and Rodney’s powerful solo brings the piece to a close over an unexpected Latin vamp. “Guts” is an elaborate study of the blues with vamp interludes leading to a blowing chorus that jumps between the related keys of B-flat and E-flat. Rodney flies through his solo, eagerly taking on all of the challenges; Sullivan imitates Rodney’s exuberant high-register wails at the top of his chorus but continues with more concentration on note choices. Then the two trumpeters give us the trumpet chase we’ve anticipated all along. It is short but thrilling, and completely within the progressive style.

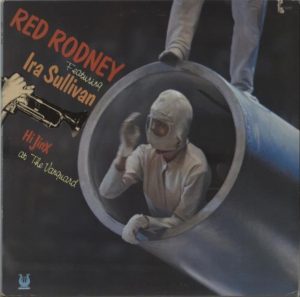

The tracks on the first Village Vanguard album represented Rodney’s original choices. He had no intention of releasing more LPs from this  session, and in the notes to the second volume, “Hi-Jinx” he claims that he didn’t know that the tapes were rolling throughout the sets. Rodney was eventually persuaded to listen again, and he approved the release. Walrath composed the title tune, a quickly-paced bebop piece with short vamp sequences tucked into the changes. Rodney plays a spirited solo that seems to jump from the speakers, and Sullivan is a little more reserved but very inspired on tenor. Whaley has a ball maneuvering the style changes both in his drum solo and through an interactive episode in the coda. Walrath’s “On the Seventh Day” starts with a uniquely winding flute melody (Sullivan, with excellent technique) before shifting to a plaintive tune for flugelhorn (Rodney at his most sensitive). This unconventional but memorable piece concludes with a return of the flute melody and an exquisite finale. Sullivan switches to alto sax for the theme and first solo on “The Days of Wine and Roses”. I can’t imagine that Sullivan would have wanted this track released as his solo includes flurries of notes, but lacks overall direction. Rodney keeps his solo simple, and that approach, echoed in Dial’s sparkling choruses, improves the overall performance. The second side features three jazz standards, starting with a free-wheeling jam on “I Remember You” for the two trumpets. Sullivan runs the changes with aplomb, and the influence of Clifford Brown can be heard in his tone and lines. Rodney’s solo bursts with joy, and as the chase ensues, he spends an impressive amount of time in the high register. Near the end of the exchanges, Sullivan (and eventually Rodney) take more chances with the harmony, gradually edging further out. Following another fine Dial solo, Berner gets the spotlight for a brief but highly effective solo. Sullivan picks up the alto again for an outstanding version of “I’ve Got it Bad and That Ain’t Good”. Beginning without accompaniment, Sullivan lets us focus on his warm, pleading tone, as he caresses this classic Duke Ellington melody. Like so many other jazz balladeers, Sullivan doesn’t play as much of the original tune as expected, but he never loses sight of the song or the unheard lyrics. Dial’s ensuing piano solo shifts the mood and style from Sullivan’s melancholy approach, but not enough to disrupt the overall performance. Sullivan closes with an impassioned cadenza which succinctly sums up the interpretation. Thelonious Monk’s “Let’s Cool One” starts with a fade-in, and this may indicate that it was paired with another melody (see the Chicago Jazz Festival performance below). Sullivan coyly twists and turns the melody in his opening flugelhorn solo, followed by Rodney and Dial exploring remote harmonies.

session, and in the notes to the second volume, “Hi-Jinx” he claims that he didn’t know that the tapes were rolling throughout the sets. Rodney was eventually persuaded to listen again, and he approved the release. Walrath composed the title tune, a quickly-paced bebop piece with short vamp sequences tucked into the changes. Rodney plays a spirited solo that seems to jump from the speakers, and Sullivan is a little more reserved but very inspired on tenor. Whaley has a ball maneuvering the style changes both in his drum solo and through an interactive episode in the coda. Walrath’s “On the Seventh Day” starts with a uniquely winding flute melody (Sullivan, with excellent technique) before shifting to a plaintive tune for flugelhorn (Rodney at his most sensitive). This unconventional but memorable piece concludes with a return of the flute melody and an exquisite finale. Sullivan switches to alto sax for the theme and first solo on “The Days of Wine and Roses”. I can’t imagine that Sullivan would have wanted this track released as his solo includes flurries of notes, but lacks overall direction. Rodney keeps his solo simple, and that approach, echoed in Dial’s sparkling choruses, improves the overall performance. The second side features three jazz standards, starting with a free-wheeling jam on “I Remember You” for the two trumpets. Sullivan runs the changes with aplomb, and the influence of Clifford Brown can be heard in his tone and lines. Rodney’s solo bursts with joy, and as the chase ensues, he spends an impressive amount of time in the high register. Near the end of the exchanges, Sullivan (and eventually Rodney) take more chances with the harmony, gradually edging further out. Following another fine Dial solo, Berner gets the spotlight for a brief but highly effective solo. Sullivan picks up the alto again for an outstanding version of “I’ve Got it Bad and That Ain’t Good”. Beginning without accompaniment, Sullivan lets us focus on his warm, pleading tone, as he caresses this classic Duke Ellington melody. Like so many other jazz balladeers, Sullivan doesn’t play as much of the original tune as expected, but he never loses sight of the song or the unheard lyrics. Dial’s ensuing piano solo shifts the mood and style from Sullivan’s melancholy approach, but not enough to disrupt the overall performance. Sullivan closes with an impassioned cadenza which succinctly sums up the interpretation. Thelonious Monk’s “Let’s Cool One” starts with a fade-in, and this may indicate that it was paired with another melody (see the Chicago Jazz Festival performance below). Sullivan coyly twists and turns the melody in his opening flugelhorn solo, followed by Rodney and Dial exploring remote harmonies.

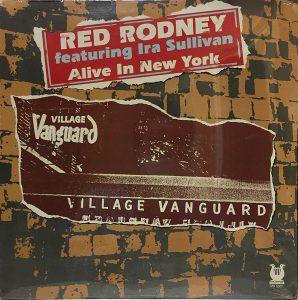

The final Vanguard LP was titled “Alive in New York”, and in retrospect, it contains some of the most interesting titles of the set. Joe Henderson’s “Recorda-Me” starts the proceedings with Rodney’s brilliant theme statement and solo contrasting with Sullivan’s warm flute improvisation. The rhythm section shifts into high Latin gear on Dial’s choruses, and that groove enhances the trades between trumpet and flute. Next comes the quintet’s first version of “Monday’s Dance”, a graceful Sullivan waltz that would be one of the group’s signature pieces. This take is much more leisurely than the Elektra-Musician studio version of the following year. The opening rubato section is stretched out and unhurried, the flute/flugel duet (unique to this recording) leaves space for each player, and Rodney plays his solo with considerable restraint. The closing interplay is tender and heart-rending. “Let’s Cool One” turns up again, with Sullivan on alto sax (less puckish and more flowing this time around), and Rodney rhythmic precise on trumpet. Dial plays his solo behind Rodney as he makes the closing announcements for the evening. But wait, there’s more! The second side includes two superb encores, a swinging medium blues Rodney’s, “Red, Hot and Blues” with burning trumpet, wailing tenor, mercurial piano, and soulful bass, followed by our first example of a Garry Dial original, “Shutters”. Sullivan, back on alto, relishes the tune’s challenging harmonic structure. Rodney chooses his notes carefully and comes out fine at the end of his solo. Dial’s solo glistens and shines before the horns return to the enticing melody.

The final Vanguard LP was titled “Alive in New York”, and in retrospect, it contains some of the most interesting titles of the set. Joe Henderson’s “Recorda-Me” starts the proceedings with Rodney’s brilliant theme statement and solo contrasting with Sullivan’s warm flute improvisation. The rhythm section shifts into high Latin gear on Dial’s choruses, and that groove enhances the trades between trumpet and flute. Next comes the quintet’s first version of “Monday’s Dance”, a graceful Sullivan waltz that would be one of the group’s signature pieces. This take is much more leisurely than the Elektra-Musician studio version of the following year. The opening rubato section is stretched out and unhurried, the flute/flugel duet (unique to this recording) leaves space for each player, and Rodney plays his solo with considerable restraint. The closing interplay is tender and heart-rending. “Let’s Cool One” turns up again, with Sullivan on alto sax (less puckish and more flowing this time around), and Rodney rhythmic precise on trumpet. Dial plays his solo behind Rodney as he makes the closing announcements for the evening. But wait, there’s more! The second side includes two superb encores, a swinging medium blues Rodney’s, “Red, Hot and Blues” with burning trumpet, wailing tenor, mercurial piano, and soulful bass, followed by our first example of a Garry Dial original, “Shutters”. Sullivan, back on alto, relishes the tune’s challenging harmonic structure. Rodney chooses his notes carefully and comes out fine at the end of his solo. Dial’s solo glistens and shines before the horns return to the enticing melody.

Rodney’s manager, Abbey Hoffer, booked Rodney and Sullivan as solo artists at first, landing engagements at the Amsterdam International Jazz Festival on August 9, and the Chicago Jazz Festival (with a concurrent booking at the Jazz Showcase) in the week surrounding Labor Day. These live sets (along with the others discussed below) enhance our understanding of the group, as the group frequently exceeds the high standard of its commercial recordings. The Amsterdam set features Red and Ira with the Jack Wilkins Trio in a particularly exhilarating concert. Guitarist Wilkins led a progressive group with bassist Ron McClure and drummer Billy Hart. McClure’s elastic lines and Hart’s flexible time mixed well with Wilkins’ free blend of contemporary rock and jazz elements. The trio’s extraordinary interplay is present throughout their 4-tune opening set. Unfortunately, that section of the concert is not on the YouTube clip linked below, but one tune, the Wilkins original “Fum” can be heard on Wilkins’ website. Rodney and Sullivan brought charts for four songs from the Vanguard session, along with a few surprises. The trio read the charts flawlessly, providing superb backing for the visiting artists.

Red and Ira opened their set with “Blues in the Guts”. Both trumpeters had mastered the shifting time feels of the Walrath composition, and they molded their solos into intriguing dramatic arcs. Wilkins proceeds fearlessly, and then things get wild in the chase sequence, as Wilkins adds his own lines to the mix. Hart’s explosive drum solo sets up the return of the head, and the drummer’s unexpected press roll throws an extra curve into the final chorus. “Mr. Oliver” features Sullivan’s expressive tenor over the rhythm section in straight, double, and free time. Rodney heads to the high register mixing lyric phrases with bop licks. Wilkins and McClure engage in a vibrant dialogue before the bassist takes over for a virtuosic solo which seems to move in several directions at once. On “What Can We Do”, Sullivan’s mournful flugel contrasts with the slightly optimistic Rodney. Wilkins’ solo is filled with intriguing note choices, as McClure follows with a straightforward approach. Sullivan returns for another solo on alto flute, but McClure continues improvising, creating another stunning dialogue. And while Hart does not ride the contours of the song as Tom Whaley did at the Vanguard, he sets a calming background with a simple straight-eight note pattern on the hi-hat. Herbie Hancock’s “Dolphin Dance” makes its first appearance in the Rodney/Sullivan repertoire. The opening rubato alto sax/guitar duet offers no clue to what follows, as the band transforms the dreamy original into a throbbing up-tempo Latin number. Once the tempo kicks in, Sullivan’s sax solo dominates the episode with Rodney goading his co-leader into collective improvisation. Wilkins takes a different approach, alternating between swing and Latin styles as he re-examines the harmonies in this radical new tempo. The three soloists improvise together over a vamp as the performance comes to a close.

“Monday’s Dance” makes a welcome return with a quiet opening trio between the two flugelhorns and guitar. Upon his entrance, McClure subtly emphasizes the waltz feel with a one-to-a-bar backing while Rodney and Sullivan weave their improvised lines. The rhythm team switches to 4/4 swing for Wilkins’ brief solo and seamlessly moves back into 3 for Sullivan’s alto solo. Sullivan goes back to flugelhorn for the final duet. With the set nearing its end, Rodney acknowledges the band, and calls for “The Red Arrow”. This would be the go-to trumpet duet in many ensuing concerts. The Amsterdam version features a brilliant duet between Sullivan and Hart, followed by a series of exciting overlapping trumpet exchanges. Hart takes a dynamic solo before the rip-roaring finale. As the band leaves the stage, the audience chants “We want more”. Sullivan returns to the microphone and tells the crowd that they’d be happy to play another two hours. Instead, Rodney and Sullivan pay tribute to the festival organizer with a loose duet on “Happy Birthday” before a sudden launch into Charlie Parker’s “Buzzy”. Sullivan’s tenor solo twists standard bop phrases like soft pretzels before re-introducing the birthday quote. Rodney develops the quote for a few bars, and throws it back to Sullivan, who has switched back to trumpet (the quick instrument swap was one of his specialties). Wilkins blows the blues changes apart before letting McClure re-establish the tonality. Trumpets and guitar play a wailing ensemble figure in exchange with Hart before returning to both “Buzzy” and “Happy Birthday”.

Less than three weeks after their success in Amsterdam, Rodney and Sullivan took the stage at Chicago’s Grant Park Pavilion. They were surrounded by old friends. Pianist Chris Anderson, bassist Victor Sproles, and drummer Wilbur Campbell were all members of the house band at the Bee Hive (Anderson was apparently Norman Simmons’ first-call sub). Billy Taylor was also at Grant Park, hosting a live broadcast of NPR’s “Jazz Alive”. The Rodney/Sullivan set was part of the Chicago Jazz Festival’s Tribute to Charlie Parker on what would have been Bird’s 60th birthday. Appropriately, the first songs are Parker originals, “Dewey Square” and “Buzzy”. Parker’s spirit is abundant throughout these tunes, with well-played theme statements, Sullivan’s Bird-like alto lines, and Rodney’s joyous trumpet. Anderson, who suffered from osteogenesis imperfecta, was not in prime form. His muddled piano lines alternated space and clutter, but the rest of the rhythm team was brilliant throughout. Campbell’s explosive drums fuel the horns as they blaze through a series of exchanges on “Buzzy” (a very different version of “Buzzy” than in Amsterdam, with no full solos and no “Happy Birthday”—although that quote would have been entirely appropriate!) “Blues in the Guts” follows with Rodney blowing fire out of his trumpet, and Sullivan’s flugelhorn attempting to replace the lid on the pressure cooker, but eventually giving up and letting loose a flurry of high notes. Anderson plays spare lines, but he seems unable to lock in with the rhythm section. With Campbell going wild on drums, the trumpet chase is insanely exciting.

Anderson redeems himself with a solo version of John Coltrane’s “Naima”. This was particularly good programming, as it let Anderson focus, and offered some necessary respite to the band and audience after a very energized opening. The quietude is maintained with a ballad medley. Sullivan takes up his alto flute for a lush and sensuous reading of “This Is Always”. The rubato feel of the opening chorus eases into a leisurely tempo as Sullivan decorates the Harry Warren melody with tender filigrees. When Sullivan finishes, Campbell starts a light Latin groove, and Rodney intones the melody of “Star Eyes”. Rodney dives into the changes for two choruses of inspired improvisation. The alto solo continues the exploration of Parker’s influence on Sullivan. Anderson finally gets into the groove, but nearly loses it again before the end of the solo. There is a little confusion in the drum exchanges (eights were called for, but Campbell jumped the gun by four bars), but the group corrected the mistake instantly. “The Red Arrow” returns, and Rodney heads for the stratosphere. As on the Amsterdam date, Sullivan plays his initial solo with the drums, and neither man disappoints. The trumpet chase puts JATP to shame, and Campbell counters with a great mallet solo. Sproles plays a full-toned and melodic solo, and Campbell steals the show again with a martial display on his snare. Sproles takes a longer solo in reply before the trumpets reprise the melody and close out with another trip up high. Mirroring the opening, the set ends with two dovetailed compositions by Thelonious Monk, “Round Midnight” and “Let’s Cool One”. “Midnight” is very dramatic with an out-of-time opening chorus with lots of interaction between the instruments. Rodney’s flugel and Sullivan’s alto sound quite stark against the strongly accented pulse, and the two share melodic responsibilities on the out chorus. “Cool” is hotter than the earlier versions, for obvious reasons. Anderson gets the first solo spot, evoking the composer. Alto and trumpet exchange fours for two choruses without any of the humorous touches of the Vanguard recordings. Unfortunately, no recordings have surfaced of this group’s tenure from that week at the Jazz Showcase. At the end of the Grant Park set, the Showcase’s owner, Joe Segal, invites the audience to the club’s late-night set saying, “We’ll just get you warmed up here”. If that was the case, what a night that must have been at the Showcase!