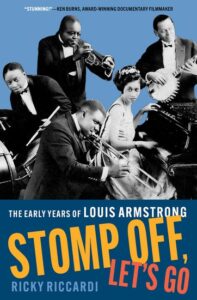

Browse through the biography section of any well-stocked music library and you will find several multiple-volume histories of composers  like Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Liszt, and Mahler. Moving along to the jazz biographies, there are many single-volume studies of the great icons, but surprisingly few expand beyond one book. The existing double-volume books on Paul Whiteman and Benny Carter, are primarily discographies, and Stanley Crouch died before completing the second half of his Charlie Parker bio, leaving Jack Chambers’ two-book study of Miles Davis‘ life and music as the most significant multi-volume jazz biography written to date. However, with the publication of Ricky Riccardi‘s “Stomp Off, Let’s Go” (Oxford) the complete life story of Louis Armstrong is now available in a series of three full-length books.

like Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Liszt, and Mahler. Moving along to the jazz biographies, there are many single-volume studies of the great icons, but surprisingly few expand beyond one book. The existing double-volume books on Paul Whiteman and Benny Carter, are primarily discographies, and Stanley Crouch died before completing the second half of his Charlie Parker bio, leaving Jack Chambers’ two-book study of Miles Davis‘ life and music as the most significant multi-volume jazz biography written to date. However, with the publication of Ricky Riccardi‘s “Stomp Off, Let’s Go” (Oxford) the complete life story of Louis Armstrong is now available in a series of three full-length books.

Riccardi’s books were published in reverse order, starting with “What a Wonderful World: The Magic of Louis Armstrong’s Later Years” (Pantheon) and followed by “Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years” (Oxford). (See my reviews here and here). Together, these two volumes covered Armstrong’s career from 1929 to his death in 1971. But when these books were published, there was no guarantee that Riccardi would have the opportunity to tell the crucial story of Armstrong’s early life and artistic development in New Orleans, Chicago, and New York. “Stomp Off, Let’s Go” fills that gap admirably, and like Riccardi’s earlier books, the most recent entry is loaded with revelations about jazz’s first great—and arguably, still most influential—artist.

Ricky Riccardi lives and breathes Louis Armstrong. As Director of Research Collections at the Louis Armstrong Museum and Archives in Corona, New York, he has gathered an extraordinary amount of information and artifacts about his favorite trumpeter and vocalist. Known as “Rickipedia” for his thorough knowledge of all things Armstrong, I have personally joked—and only partially in jest—that Riccardi could probably rattle off Armstrong’s shoe sizes from various parts of his life. The love that Riccardi holds for Armstrong can be felt on every page of his three-volume biography, and except for one instance noted below, Riccardi is not afraid to question Armstrong’s memory or his decisions.

“Stomp Off” benefits from several newly-tapped resources, including a copy of Armstrong’s original (and unexpurgated) manuscript for his autobiography “Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans“, interview notes for the unpublished memoirs of Armstrong’s second wife and major collaborator, Lil Hardin Armstrong, and interviews with Armstrong’s sister, Beatrice (better known as “Mama Lucy”) Armstrong. In addition, Riccardi has full access to Louis’ library of open-reel tapes, which include many dubbed commercial recordings, sometimes with spoken commentary and musical additions by the great man himself. The online availability of local newspapers—including those owned and operated by African-Americans for their communities—enriches Armstrong’s story with newly discovered facts. To pick out one example at random, Riccardi reveals that the young Armstrong served two stays at the Colored Waif’s Home and that he was not involved in the institution’s music program until his second visit.

Louis Armstrong always gave his birthdate as July 4, 1900. His birth certificate has never been located and may be lost forever. However, Tad Jones‘ discovery of Armstrong’s baptismal certificate led the jazz community to accept a revised birthdate of August 4, 1901. While Riccardi acknowledges Jones’ pioneering research, he has not fully endorsed the new date. In an argument that first appeared on Riccardi’s blog several years ago, he offers evidence supporting July 4, 1901 as Armstrong’s actual birthdate. If nothing else, Riccardi shows that there is room for doubt. Regardless of whichever date is correct (or another one that might pop up in further research) it is good to have this discussion in permanent printed form. As Riccardi states, the best part is undeniable: Louis Armstrong was born.

Riccardi uses the first half of the book (nearly to the exact middle page!) to tell of Armstrong’s life in New Orleans and his development into a professional musician. He was born into a dirt-poor home in the toughest part of town. His mother was a prostitute who was arrested on several occasions, and his father was frequently absent. Armstrong left school in the fifth grade and became the family’s principal breadwinner. He went to work with the Jewish Karnofsky family collecting junk and delivering coal through many neighborhoods, including Storyville, the city’s legalized red-light district. Riccardi’s exceptionally detailed and cross-referenced account of Armstrong’s association with the Karnofskys clarifies the entire story and dismisses many online rumors. Armstrong sang in a boy’s quartet before being sent to the Waif’s Home, but his introduction to the cornet focused his love for music and strengthened his desire to make his living—and eventually fame—playing jazz. He learned from many of New Orleans’ finest jazz musicians, including Joe “King” Oliver, who Armstrong said was the only person who could convince him to leave his hometown.

The stories of Armstrong’s subsequent triumphs have been told many times, including his time in Chicago, as second cornet in Oliver’s band, and in New York, as a featured soloist in Fletcher Henderson‘s Orchestra. Riccardi retells the tales with great enthusiasm, keeping his narrative vibrant and compelling. An earlier draft also contained detailed discussions of Armstrong’s recordings with Oliver, but at the suggestion of his editors, this material was removed; it later structured Riccardi’s Grammy-winning notes for Archeophone’s “King Oliver Centennial” collection (see my review here. However, I am most grateful that Riccardi included an analysis of Armstrong’s recordings made with clarinetist/soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet, who was Armstrong’s only equal as an improvising soloist in 1924 and 1925. Bechet was a powerhouse musician with an ego to match, and he was not satisfied with the standard New Orleans tradition of a dominant trumpet lead with a lesser woodwind obbligato played in the background. Bechet unabashedly pushed himself into the spotlight: his preference for the soprano sax over the clarinet reflected his desire for more sound, and Riccardi attributes his one-time use of a bass sarrusophone as a further attempt to drown out Armstrong.

The artistic tug-of-war between Bechet and Armstrong continued in a December 22, 1924 recording of “Cake Walking Babies from Home” for the Gennett label. Riccardi notes the two men were in top form as they vied for the lead role, but that a missed note by Armstrong caused Bechet to smell blood, and after that, he dominated the recording. Seventeen days later, they recorded the same song for OKeh, with significantly different results. In a vivid passage, Riccardi describes the dramatic showdown as if it were a boxing match:

After Eva Taylor‘s lively vocal, Bechet picks up where he left off [on the Gennett recording] unleashing combinations, growling through another break, and swarming Armstrong in the ensembles, unwilling to let him play the lead.

It’s at this point where Armstrong seems to say “ENOUGH!” In an instant, he unleashes perhaps the angriest note of his entire career before rhythmically alternating two notes in the exact same way he once recalled Joe Oliver doing it…. Armstrong might have been channeling Oliver’s ideas but the heat, the power, the fire, the swing, that’s the Louis Armstrong who changed the world. Armstrong comes on so hot, Bechet almost completely disappears from the ensemble, resorting to quietly playing the melody, and for once, staying out of Armstrong’s way.

Having regained control, Armstrong takes a mind-boggling break, repeating a tricky phrase in both the upper and lower registers of his horn, executing it with thrilling precision. He doesn’t let up until he reaches the song’s final four-bar break, which he pounces on, daringly walking a rhythmic tightrope before ripping up to a high note and concluding with some downhome blues, all in a matter of seconds. Bechet re-emerges at the very end, but for all intents and purposes, Armstrong scored a knockout victory during the rematch.

Riccardi leaves the story at this point, but it is interesting to note that on two remaining recordings pairing Bechet and Armstrong, “Pickin’ on Your Baby” from the above session and “Papa-De-Da-Da” from two months later, Bechet is relegated to the background (either by his own choice or someone else’s) playing the melody behind Armstrong on the former track, and a written harmony part on the latter.

The above passage shows Riccardi’s strengths as a writer. Unfortunately, Riccardi’s text is full of vulgarities. For the first time in the Armstrong trilogy, some of these words have crept into the chapter titles. We live in a dangerous time for free-thinkers, with conservatives who ban books because they see a dirty word, and not because they’ve read the complete text. This book is simply too important to risk a sudden removal from bookshelves because of the careless use of language.

There is no shortage of mythology surrounding Louis Armstrong, but at times, Riccardi is reluctant to debunk apocryphal stories, even when doing so exposes a greater truth. For example, his account of Armstrong’s “Heebie Jeebies” adds additional details but still ties itself to a century-old legend. Recorded in February 1926 for OKeh Records, “Heebie Jeebies” contained Armstrong’s first extended scat solo. Armstrong was eager to sing on record, but he had been rebuffed many times because of the gravelly nature of his voice. When “Heebies” was converted into a vocal number at the recording session, Armstrong seized upon the opportunity, dashing off a few lyrics on a spare piece of paper, and then fashioning an arrangement featuring two consecutive vocal choruses. Apparently, Armstrong had the scat solo in mind, but he kept it a secret until it was safely preserved in wax.

As scat had not been recorded before, there was a clear need to explain what Armstrong was singing. And someone—probably from OKeh’s publicity department—concocted one of the most improbable stories among the many legends of jazz history. The story claimed that Armstrong dropped the lyric sheet while recording the vocal, and that he improvised using nonsense syllables to keep the take going while the errant sheet was retrieved from the floor. The story can be proved false by simply listening to the recording. There are only two minor flaws on the entire side, a minor lyric flub in the first vocal chorus and a missed spoken response by Kid Ory in the coda. Neither of these gaffes had any effect on the scat solo. Armstrong is poised and completely secure throughout both vocal choruses. After a casual reading of the lyrics in the first chorus, the scat solo starts at the beginning of the second chorus, just as planned. There is a short reprise of the lyric before the band returns. As Armstrong’s vocal was accompanied solely by Johnny St. Cyr’s banjo, any studio disasters would have been audible on the recording. There are no such sounds. Please listen for yourself.

With abundant proof that “Heebie Jeebies” was performed without any studio mishaps, we don’t know why OKeh created such a ridiculous story. Whether intended or not, the light-hearted description probably ensured Armstrong’s safety when touring in the South. A bold statement from OKeh such as “Louis Armstrong premieres a new jazz innovation” would translate to the Ku Klux Klan as “Proud n***** doesn’t know his place”. As we all know, the KKK usually transformed their anger into violent actions. The continued presence of extreme racism throughout Armstrong’s life might explain why he and the rest of the band members persisted with the OKeh cover story. But in his attempt to validate the old legend, Riccardi missed this important connection.

Nearly 100 years later, all of the danger from “Heebie Jeebies” is long past. The cover story has outlived its usefulness and needs to be retired. Life in 2025 is much different from 1926, but we still fight for truth. With a pathological liar as president and AI programs that garble and distort the information fed into them, the truth can be hard to establish. The history of our beloved music, weighed down with legends and ridiculous stories, must be protected for future generations. The “Heebie Jeebies” story is a minor slip in this book, but it can (and should be) revised in a future edition. It should not impede readers from buying this book and the two earlier volumes. Ricky Riccardi’s three-volume biography is a monument to the importance of Louis Armstrong. There are many more jazz icons still waiting for the same honor.