Many of today’s jazz vocalists strive to find unique song repertoire, but for Catherine Russell, it’s a matter of looking backward instead of forward. Russell, the daughter of the late jazz musicians Luis Russell and Carline Ray,  has always searched for songs which her dad’s former employer, Louis Armstrong, would term “the good ol’ good ones”. Her new album “Alone Together” (Dot Time 9083) features a baker’s dozen of songs primarily written before 1950. Utilizing a band of young traditionalists, including trumpeter Jon-Erik Kellso, trombonist John Allred, tenor saxophonist Evan Arntzen, pianist Mark Shane, guitarist Matt Munisteri, bassist Tal Ronen, and drummer Mark McLean, Russell performs this classic music in ways that aren’t terribly surprising, but display strong musicianship throughout. The ensemble plays with propulsive swing and admirable precision, while Russell’s interpretations of songs like “Alone Together”, “You Turned the Tables on Me”, and “How Deep is the Ocean” shows a mature understanding of the lyrics and their meanings. In addition, she swings with minimal effort, focusing on the original melodies with only a few well-chosen melodic variations. “When Did You Leave Heaven”, features a country-styled background that would sink a lesser performer, but Russell uses the arrangement to make a statement of uncommon perseverance and strength. Russell is at her best on the blues, and her loose, soulful versions of “Early in the Morning” (over a rolling New Orleans groove) and the double-entendre “He May Be Your Dog, But He’s Wearing My Collar” (to a rustic country blues setting) are album highlights. “Shake Down the Stars”, a tune I usually associate with Jeri Southern, is presented here in a basic swing arrangement, but Russell’s interpretation brings a completely different emotion to the song than in Southern’s detached—but equally compelling—rendition. This album will doubtlessly please Russell’s devoted fans, and with enough radio play, it will generate many more followers.

has always searched for songs which her dad’s former employer, Louis Armstrong, would term “the good ol’ good ones”. Her new album “Alone Together” (Dot Time 9083) features a baker’s dozen of songs primarily written before 1950. Utilizing a band of young traditionalists, including trumpeter Jon-Erik Kellso, trombonist John Allred, tenor saxophonist Evan Arntzen, pianist Mark Shane, guitarist Matt Munisteri, bassist Tal Ronen, and drummer Mark McLean, Russell performs this classic music in ways that aren’t terribly surprising, but display strong musicianship throughout. The ensemble plays with propulsive swing and admirable precision, while Russell’s interpretations of songs like “Alone Together”, “You Turned the Tables on Me”, and “How Deep is the Ocean” shows a mature understanding of the lyrics and their meanings. In addition, she swings with minimal effort, focusing on the original melodies with only a few well-chosen melodic variations. “When Did You Leave Heaven”, features a country-styled background that would sink a lesser performer, but Russell uses the arrangement to make a statement of uncommon perseverance and strength. Russell is at her best on the blues, and her loose, soulful versions of “Early in the Morning” (over a rolling New Orleans groove) and the double-entendre “He May Be Your Dog, But He’s Wearing My Collar” (to a rustic country blues setting) are album highlights. “Shake Down the Stars”, a tune I usually associate with Jeri Southern, is presented here in a basic swing arrangement, but Russell’s interpretation brings a completely different emotion to the song than in Southern’s detached—but equally compelling—rendition. This album will doubtlessly please Russell’s devoted fans, and with enough radio play, it will generate many more followers.

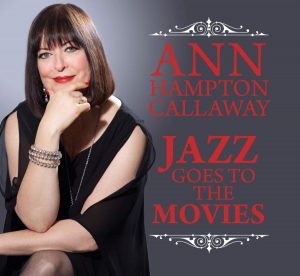

Ann Hampton Callaway’s latest album also draws on songs from the first half of the 20th century, but her arrangements are inspired by later models than  Russell’s. “Jazz Goes to the Movies” (Shanachie 5464) may not be the most original album concept, but the strength of the individual songs and the superb performances by Calloway, Jimmy Greene (tenor and soprano saxes), Ted Rosenthal (piano), Martin Wind (bass) and Tim Horner (drums) allow us to forget the concept and dig into the music. Since dedicating herself to jazz singing several years back, Calloway has mastered all aspects of the art: she brings her life experience to her interpretation of lyrics, she swings with abandon, and her scat singing is thrillingly executed. “Blue Skies” starts with the verse (did you know that song had a verse? I didn’t!) and moves into the first chorus as a ballad. Then, as if it were the most natural segue in the world, the tempo shifts to medium-fast swing for an additional chorus of the song, and short solos by Callaway and the band. Callaway’s way of engaging listeners is especially apparent on an unusual medium-up arrangement of “As Time Goes By”. On paper, it seems that such an arrangement would destroy the sentiment of the lyric, but Callaway never lets us forget that lyric and she delivers it with the same intensity that would mark a ballad performance. On a tune that is frequently taken at blistering speeds, Callaway’s bossa nova version of “The Way You Look Tonight” restores the tender sentiments of Dorothy Fields’ lyric. The album’s best track is Hoagy Carmichael’s “The Nearness of You”, taken at a slow ballad tempo, and featuring some of Callaway’s finest expressive moments. She brings an abiding passion to Ned Washington’s lyrics, and her melodic variations enhance what was already a glorious melody. Greene’s passionate solo is the perfect bridge to Callaway’s exquisite final half-chorus. “Just One of Those Things” moves along at a brisk pace, with Greene’s double-tracked soprano sax, fleet solos by Greene and Rosenthal, and an exciting wordless passage for voice and saxophone. As usual with Callaway’s album, there are more highlights than can be described in a short review. Just buy this CD—you won’t regret it.

Russell’s. “Jazz Goes to the Movies” (Shanachie 5464) may not be the most original album concept, but the strength of the individual songs and the superb performances by Calloway, Jimmy Greene (tenor and soprano saxes), Ted Rosenthal (piano), Martin Wind (bass) and Tim Horner (drums) allow us to forget the concept and dig into the music. Since dedicating herself to jazz singing several years back, Calloway has mastered all aspects of the art: she brings her life experience to her interpretation of lyrics, she swings with abandon, and her scat singing is thrillingly executed. “Blue Skies” starts with the verse (did you know that song had a verse? I didn’t!) and moves into the first chorus as a ballad. Then, as if it were the most natural segue in the world, the tempo shifts to medium-fast swing for an additional chorus of the song, and short solos by Callaway and the band. Callaway’s way of engaging listeners is especially apparent on an unusual medium-up arrangement of “As Time Goes By”. On paper, it seems that such an arrangement would destroy the sentiment of the lyric, but Callaway never lets us forget that lyric and she delivers it with the same intensity that would mark a ballad performance. On a tune that is frequently taken at blistering speeds, Callaway’s bossa nova version of “The Way You Look Tonight” restores the tender sentiments of Dorothy Fields’ lyric. The album’s best track is Hoagy Carmichael’s “The Nearness of You”, taken at a slow ballad tempo, and featuring some of Callaway’s finest expressive moments. She brings an abiding passion to Ned Washington’s lyrics, and her melodic variations enhance what was already a glorious melody. Greene’s passionate solo is the perfect bridge to Callaway’s exquisite final half-chorus. “Just One of Those Things” moves along at a brisk pace, with Greene’s double-tracked soprano sax, fleet solos by Greene and Rosenthal, and an exciting wordless passage for voice and saxophone. As usual with Callaway’s album, there are more highlights than can be described in a short review. Just buy this CD—you won’t regret it.

Of course, great songs have been written in the years since 1950, and while the quantity of songs may not be as high as when Gershwin, Kern, Arlen, Rodgers and Berlin reigned supreme, there is ample material for any jazz vocalists willing to challenge themselves and their audiences. Which makes it all the more curious that the music of Stephen Sondheim (arguably the most intriguing songwriter working today) has not been fully accepted into the jazz repertoire. Part of the problem is that Sondheim’s music is so tied to his Broadway shows that it is hard to imagine them in any other context. Sarah Vaughan’s virtuosic arrangement of “Send in the Clowns” retained the piano arpeggios from the original score, and “A Stephen Sondheim Collection”, a tribute album recorded by Jackie Cain and Roy Kral hewed closely to the Broadway arrangements on several of its selections.

Cyrille Aimée, whose initial experience with singing Sondheim came only six years ago during a series of City Center performances in New York, has taken a fresh look at this music, setting it in new and exciting arrangements. The results have been captured on her new album, “Move On: A Sondheim  Adventure” (Mack Avenue 1144). The opening track, “When I Get Famous”, is an a cappella set-piece featuring Cyrille and a digital looping machine—a far cry from anything heard in a Sondheim musical! A joyous New Orleans groove propels the optimistic “Take Me to the World”, in which Cyrille finds room for an extended scat solo. The verse of “Love, I Hear” has a recognizable touch of Sondheim’s style, but the style soon changes to a loose-limbed jazz waltz featuring Cyrille’s bubbly vocals, Mathias Levy’s elegant violin, Assaf Gleizner’s cushiony Rhodes and Jérémy Bruyère’s dancing bass. The same rhythm section (with Thomas Enhco subbing for Gleizner on acoustic piano) transforms “Loving You” into a smooth-swinging jazz feel. The borderline neurotic lyrics of “Marry Me a Little” are tempered by Diego Figueiredo’s acoustic guitar and an elegant string quartet. As she does on all of these tracks, Cyrille’s exquisite diction and her persuasive delivery retain the original messages intended by the composer (nowhere better than on the title track) and it is to Sondheim’s credit that his words and music can retain its power, even in the most radical transformations, including the burning samba treatment of “Being Alive”, the double-tempo Gypsy jazz arrangement of “So Many People” or the electronics-infused setting of “I Remember”. Cyrille’s mixed meter rendition of “Not While I’m Around” may lack the fierce intensity of the version from “Sweeney Todd”, but we still believe that she will protect her lover from all adversaries. I am particularly impressed with the bass/vocal duet on “They Ask Me Why I Believe in You” and the gospel arrangement of “No One is Alone” (featuring Bruyère and guitarist Ralph Lavital, respectively), and I wonder if Sondheim—who claims to know little about jazz—was surprised at the new settings. When he first heard Cyrille sing one of his songs at City Center, Sondheim admitted that he broke into tears. He attended Cyrille’s performance of this music at the Manhattan jazz club Birdland earlier this year, and the photos show him to be very pleased. Perhaps Cyrille’s example will inspire other performers to examine Sondheim’s work as songs, not as mere Broadway specialties.

Adventure” (Mack Avenue 1144). The opening track, “When I Get Famous”, is an a cappella set-piece featuring Cyrille and a digital looping machine—a far cry from anything heard in a Sondheim musical! A joyous New Orleans groove propels the optimistic “Take Me to the World”, in which Cyrille finds room for an extended scat solo. The verse of “Love, I Hear” has a recognizable touch of Sondheim’s style, but the style soon changes to a loose-limbed jazz waltz featuring Cyrille’s bubbly vocals, Mathias Levy’s elegant violin, Assaf Gleizner’s cushiony Rhodes and Jérémy Bruyère’s dancing bass. The same rhythm section (with Thomas Enhco subbing for Gleizner on acoustic piano) transforms “Loving You” into a smooth-swinging jazz feel. The borderline neurotic lyrics of “Marry Me a Little” are tempered by Diego Figueiredo’s acoustic guitar and an elegant string quartet. As she does on all of these tracks, Cyrille’s exquisite diction and her persuasive delivery retain the original messages intended by the composer (nowhere better than on the title track) and it is to Sondheim’s credit that his words and music can retain its power, even in the most radical transformations, including the burning samba treatment of “Being Alive”, the double-tempo Gypsy jazz arrangement of “So Many People” or the electronics-infused setting of “I Remember”. Cyrille’s mixed meter rendition of “Not While I’m Around” may lack the fierce intensity of the version from “Sweeney Todd”, but we still believe that she will protect her lover from all adversaries. I am particularly impressed with the bass/vocal duet on “They Ask Me Why I Believe in You” and the gospel arrangement of “No One is Alone” (featuring Bruyère and guitarist Ralph Lavital, respectively), and I wonder if Sondheim—who claims to know little about jazz—was surprised at the new settings. When he first heard Cyrille sing one of his songs at City Center, Sondheim admitted that he broke into tears. He attended Cyrille’s performance of this music at the Manhattan jazz club Birdland earlier this year, and the photos show him to be very pleased. Perhaps Cyrille’s example will inspire other performers to examine Sondheim’s work as songs, not as mere Broadway specialties.