The “St. Louis Blues” is perhaps the most venerable of all standards. Composed and published in 1914 by W.C. Handy, the song was not the first to incorporate the blues (Handy’s 1911 “Memphis Blues” has that honor), but it was Handy’s greatest success, recorded thousands of times by musicians of nearly every genre. Tom Lord’s online “The Jazz Discography” lists over 1800 jazz or jazz-related versions dating from 1915 to 2010 (and that does not include alternative titles such as “The St. Louis Blues Cha-Cha”).

The “St. Louis Blues” is perhaps the most venerable of all standards. Composed and published in 1914 by W.C. Handy, the song was not the first to incorporate the blues (Handy’s 1911 “Memphis Blues” has that honor), but it was Handy’s greatest success, recorded thousands of times by musicians of nearly every genre. Tom Lord’s online “The Jazz Discography” lists over 1800 jazz or jazz-related versions dating from 1915 to 2010 (and that does not include alternative titles such as “The St. Louis Blues Cha-Cha”).

It is said that Handy was inspired to write the song after hearing a woman in the street sing My man’s got a heart like a rock cast in the sea. While the location of the story has changed over the years, there’s little evidence to contradict the story as a whole. The three-note motive that dominates the final chorus (Got the Saint/Louis Blues/Just as blue/as—I/can be) was said to be derived from a black preacher’s incantation during his church offering. What made the song unique was its 16-bar tango section which alternates with the 12-bar blues choruses. In his autobiography, Handy describes an early performance: When St Louis Blues was written, the tango was in vogue. I tricked the dancers by arranging a tango introduction, breaking abruptly into a low-down blues. My eyes swept the floor anxiously. Then suddenly, I saw lightning strike. The dancers seemed electrified. Something within them came suddenly to life. An instinct that wanted so much to live, to fling its arms to spread joy, took them by the heels.

The original sheet music lays out the form as AABA with the A sections 12-bar blues and the B, a 16-bar tango. The final A is marked with a repeat. There are lyrics for three choruses of the AAB and 5 choruses of the final A. The familiar I hate to see the evening sun go down lines appear as the first stanza, and the Went down to the gypsy to get my fortune told lyric recorded by Louis Armstrong in 1954 is the first part of the second. But the second A of the second chorus, Gypsy done told me, don’t you wear no black/Go to St. Louis, you can win him back, does not appear in any recordings that I’ve heard. In the recordings discussed below, we’ll hear lyrics that were part of the original song (I love my man like a schoolboy loves his pie) and several that were not (If you don’t like my peaches, why do you shake my tree?).

The recordings discussed below were included in a compilation I created in 2003 which collected 48 different recordings of the Handy classic recorded between 1925 and 1991. I do not claim that my selections are a definitive collection, but they offer the song in a wide variety of approaches, styles, keys and tempos. Many of the major innovators are included (most in multiple versions) and there are several surprising renditions along the way. Most of the recordings can be found in MP3 editions online and the links below correspond to sites where those recordings can be purchased.Because my list was created for a CD collection, I left out several early recordings of the song that featured only the melody and no improvisation. These omissions include recordings by James Reese Europe, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and W.C. Handy himself. Obviously, with over 3 hours of music and 4 dozen versions of the same song, there was no need to include several recordings that simply stated the melody. However, they have obvious historical value as the earliest renditions of the Handy classic.

The earliest recording discussed here is also an undisputed classic: Bessie Smith’s 1925 Columbia version with Louis Armstrong on cornet and Fred  Longshaw on harmonium. Recorded just 9 years after the song’s original publication, “St. Louis Blues” was already considered a classic ofthe repertoire and Smith gives the song a stately and dignified performance. The tempo is extremely slow and they only get through one full AABA chorus in the three minutes of recording time. Smith’s vocal includes several expressive slides, but she leaves the vocalized effects to Armstrong. It sounds like Armstrong is playing with a straight mute and his accompaniment is restrained, so not to take the listener’s attention from Smith and the composition. The wheezy reed organ sounds like it belongs in an old southern church, which ties the sacred harmony of hymns to the secular feeling of the blues.

Longshaw on harmonium. Recorded just 9 years after the song’s original publication, “St. Louis Blues” was already considered a classic ofthe repertoire and Smith gives the song a stately and dignified performance. The tempo is extremely slow and they only get through one full AABA chorus in the three minutes of recording time. Smith’s vocal includes several expressive slides, but she leaves the vocalized effects to Armstrong. It sounds like Armstrong is playing with a straight mute and his accompaniment is restrained, so not to take the listener’s attention from Smith and the composition. The wheezy reed organ sounds like it belongs in an old southern church, which ties the sacred harmony of hymns to the secular feeling of the blues.

Moving to the early big bands, Fletcher Henderson’s 1927 version (as “The Dixie Stompers”) is a Don Redman reworking of a Mel Stitzel stock arrangement. Tommy Ladnier is the main cornet soloist and his solos show the influence of both Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke. Bessie Smith’s favorite cornetist, Joe Smith, comes up later in a muted solo and he makes great use of a single melodic idea. There’s a different stock arrangement shared in the 1929 Louis Armstrong recording and the 1930 version by Cab Calloway. The Armstrong is the non-vocal “alt take B” rediscovered in the 1990s, which leaves room for solos by trumpeter Henry “Red” Allen, trombonist J.C. Higginbotham and clarinetist Albert Nicholas in addition to Armstrong. Allen was still heavily influenced by Armstrong and he utilizes Armstrong’s method of swinging and developing a simple motive to build his solo. In fact, when Armstrong solos, he uses that same method in both creating his solo statement and leading the final ensemble. And while many of Louis’ later big bands did not swing well, this ensemble features some of the finest swing of its era. Cab Calloway’s version starts differently than Louis’, but the same punch figures appear in the final chorus. Calloway’s vocal is prime early hipster, barely touching on Handy’s lyric and moving into hysterical gibberish at the end. Calloway holds a single note through most of the first chorus, which predicts an effect played by Buster Bailey on the John Kirby version of 1942. Red Nichols’ 1930 radio transcription version opens with a spoken introduction that acknowledges that listeners have heard the song many times before, but that Nichols’ arrangement was a “furnace cooked, Hades approved hot mama-papa version” of the standard. The opening melodic statement and Glenn Miller’s trombone solo fail to live up to the announcement’s hype, but Benny Goodman’s solo is a real treasure with stunning angular lines, deep blues feeling and flawless technique. After Joe Sullivan’s rather fussy piano and Nichols’ soulful cornet, there is a sudden tempo jump at the coda.

As noted in an earlier historical essay, Fats Waller recorded organ versions of “St. Louis Blues” at the beginning and ending of his career. He also recorded several piano versions, including an interesting piano duet with Bennie Payne in 1930. Like the organ versions, this duet opens with a bit of the tango section. But when the pianists move to the blues section, the melody is buried below a high register improvisation in octaves. The melody predominates again when the tango returns, and remains audible in the final blues chorus. The arrangement was not worked out carefully in advance and there are several spots where the pianist’s chords and rhythms clash. It seems that both pianists used octaves to raise their solo lines over the general din below. By the final chorus, both pianists lock into a groove. Art Tatum’s 1933 solo recording comes from his debut session, and we can hear some Waller-esque ripples from Tatum’s right hand. While Tatum’s style developed throughout the 30s, much of his core style was already in place by the time of this recording. His left hand is beautifully modulated throughout and his smooth walking tenths contribute to the swing, and camouflage a few mild reharmonizations. Near the end of the performance, there is a stunning example of Tatum’s abstract relationship to time where his right hand piles one idea on top of another while he maintains the tempo with his left. Is it any wonder that when some pianists heard this recording, they thought they were hearing two pianists?

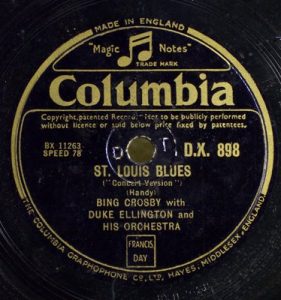

With the onset of the Depression, record sales plummeted. At Brunswick Records, Jack Kapp boosted the sales of his artists by bringing together his  top stars for recorded collaborations. In 1932, he paired his star vocalist, Bing Crosby, with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Cootie Williams opens the recording with growling trumpet over moaning saxes, and then hands the lead over to trombonist Joe Nanton before Crosby enters with the melody. Crosby was still close to his jazz roots during this period and his performance of the melody seems to veer between straight pop singing and a looser jazz approach. The tempo picks up for Johnny Hodges’ alto solo and then Crosby scats a chorus, singing convoluted lines on top of the beat. Then the original tempo returns for a brief coda, Crosby slides back into his pop style, and the performance ends with a quick brass fanfare.

top stars for recorded collaborations. In 1932, he paired his star vocalist, Bing Crosby, with the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Cootie Williams opens the recording with growling trumpet over moaning saxes, and then hands the lead over to trombonist Joe Nanton before Crosby enters with the melody. Crosby was still close to his jazz roots during this period and his performance of the melody seems to veer between straight pop singing and a looser jazz approach. The tempo picks up for Johnny Hodges’ alto solo and then Crosby scats a chorus, singing convoluted lines on top of the beat. Then the original tempo returns for a brief coda, Crosby slides back into his pop style, and the performance ends with a quick brass fanfare.

The Boswell Sisters recorded their studio version of “St. Louis Blues” in late May, 1935. This radio version was made a few days later and is much looser than the commercial 78. It contains many hallmarks of the Boswell’s style. On the opening chorus, the sisters sing in three-part harmony but with the rhythmic flexibility of a solo singer. Connee Boswell takes the tango section as a solo. There is a sudden tempo jump for the final choruses, a chanting band vocal, a stunning harmonic glissando by the sisters and an effective series of dynamic contrasts near the end. The Dorsey Brothers Orchestra recorded several sides with the Boswells; their raucous instrumental version of “St. Louis Blues” dates from August 1934. Both Tommy and Jimmy get solo spots, along with an unidentified trumpeter. Glenn Miller’s arrangement has excellent variations for the trombones and the saxes, but the whole thing starts to wind down around the two-minute mark and the remaining minute seems to be mere padding.

The next four big band versions are all from live performances. The first two, by Artie Shaw (1939) and Benny Goodman (1937) both stem from the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York. Shaw’s is propelled by the drums of Buddy Rich, and the leader’s clarinet glides over the immaculate brass and reed sections. Tony Pastor contributes a booting tenor solo between Shaw’s two solo turns. Shaw’s improvised lines aren’t loaded with catchy melodies, but his technique and concept is very sound, and he sounds quite inspired. Yet this band fell apart just three weeks later when the leader walked off the bandstand and moved to Mexico. Goodman’s version is of the polished Fletcher Henderson arrangement (not the Redman chart heard above). Like Shaw’s band, the Goodman crew were expert technicians and while the rhythm section had issues with swing, they sound relaxed and comfortable here. During the performance, Goodman was enjoying the groove so much that he signaled to keep the tune going. Harry James responded with a fiery trumpet solo, backed by a solid backbeat from Gene Krupa and the riffing saxes, and then Jess Stacy experimented with delayed right hand patterns before the band kicked into the final choruses from Count Basie’s “One O’Clock Jump”. Basie was a newcomer to the Big Apple in 1937 and his live version comes from a broadcast at the Chatterbox in Pittsburgh’s William Penn Hotel. Recorded in the last five minutes of the program, it sounds like the band is playing a head arrangement to fill the time. The rough, unpolished nature of the band only adds to the excitement of this recording. Basie discographer Chris Sheridan  lists Joe Keyes and George Hunt as the trumpet and trombone soloists that precede Jimmy Rushing’s ebullient vocal. Rushing is followed by prime examples of Lester Young and Buck Clayton, and some powerful riffing by the band. The biggest surprise may be the raw, earthy violin of Claude Williams. Williams had come East with Basie, and played both solo violin and rhythm guitar with the band (Freddie Green, who became an indelible part of the Basie rhythm section had not yet taken his spot). The version by Duke Ellington comes from the final moments of his 1940 concert in Fargo, North Dakota. Ellington’s piano intro is rather oblique and the opening chorus is rather disorganized as members of the band try to find their copies of the arrangement. By the time Barney Bigard starts his clarinet solo, the band has settled into a medium-fast groove. Ellington modulates into a new key, and Ivie Anderson sings a wide variety of blues stanzas, including the earliest version I’ve found of the peach tree lyrics. Ben Webster glides in for an extended solo punctuated by Sonny Greer’s drums, Trombonist Joe Nanton quotes “Whistle While You Work” to start his solo turn and the band offers expressive backgrounds that eventually overwhelm the soloist. The arrangement sounds like it’s heading toward “Black and Tan Fantasy” but instead, it makes an abrupt jump to “Rhapsody In Blue” to signal the end of the evening’s music.

lists Joe Keyes and George Hunt as the trumpet and trombone soloists that precede Jimmy Rushing’s ebullient vocal. Rushing is followed by prime examples of Lester Young and Buck Clayton, and some powerful riffing by the band. The biggest surprise may be the raw, earthy violin of Claude Williams. Williams had come East with Basie, and played both solo violin and rhythm guitar with the band (Freddie Green, who became an indelible part of the Basie rhythm section had not yet taken his spot). The version by Duke Ellington comes from the final moments of his 1940 concert in Fargo, North Dakota. Ellington’s piano intro is rather oblique and the opening chorus is rather disorganized as members of the band try to find their copies of the arrangement. By the time Barney Bigard starts his clarinet solo, the band has settled into a medium-fast groove. Ellington modulates into a new key, and Ivie Anderson sings a wide variety of blues stanzas, including the earliest version I’ve found of the peach tree lyrics. Ben Webster glides in for an extended solo punctuated by Sonny Greer’s drums, Trombonist Joe Nanton quotes “Whistle While You Work” to start his solo turn and the band offers expressive backgrounds that eventually overwhelm the soloist. The arrangement sounds like it’s heading toward “Black and Tan Fantasy” but instead, it makes an abrupt jump to “Rhapsody In Blue” to signal the end of the evening’s music.

While the big bands dominated the jazz scene in the late 30s and early 40s, some of the best music of the era came from soloists and small groups. Not all of these groups were situated in New York, of course, and two of the finest soloists of the era were not even in the United States. Violinist Stéphane Grappelli and guitarist Django Reinhardt were founding members of Paris’ Quintette du Hot Club de France. Their recording of “St. Louis Blues” is billed under Grappelli’s name. Still, Reinhardt is featured for all but the last minute of the recording. His unaccompanied introduction might be mistaken for that of a classical player, but when he moves into the slow, walking tempo of the opening chorus, one recognizes that he is a dedicated jazz musician. He utilizes bent notes and flashy runs in the blues choruses and emphasizes the tango melody by playing in parallel octaves. When the blues section returns, the tempo increases and Reinhardt climaxes his solo with block chords and one of his classic guitar rolls. Reinhardt remains the center of attention even behind Grappelli, as the guitarist accompanies with choppy block chords and rolls at the turnarounds. Albert Ammons was a giant of boogie-woogie piano, but he was not limited by the style. On his 1939 Solo Art recording of “St. Louis Blues”, his left hand patterns alternate between eight-to-the-bar boogie and four-beat stride. He tends to switch to the boogie pattern whenever his right hand patterns seem to call for it, but otherwise he seems perfectly happy playing in the manner of other swing pianists.

In addition to being husband and wife for a few years, Maxine Sullivan and John Kirby had a close musical association during the Swing Era. Kirby was the bassist on Sullivan’s 1938 version of “St. Louis Blues” with a small band led by pianist Claude Thornhill. Buddy Rich’s drums seem a little heavy for the cool-voiced singer, but Bobby Hackett provides superb accompaniment on cornet. Sullivan sings the song straight with virtually no melodic embellishments, and her detached delivery seems at odds with the material. In fact, it is not until the last choruses of the record that she starts to loosen up and swing with the band. On Kirby’s sextet version from 1942, the tempo is quite fast and the section work extremely tight. Buster Bailey is the star of the show, not just for the long held note referred to above, but in his dominance of the opening choruses and his fluid clarinet solo over the tango section. Charlie Shavers delivers an intense, tightly muted trumpet solo, and Billy Kyle sparkles on piano before Bailey returns to show off his skills at circular breathing.

The term “record album” actually dates back to the days of the 78rpm shellac record, and refers to a group of related discs packaged together in a book-like container. In 1940, John Hammond and Leonard Feather decided to create a W.C. Handy tribute album featuring newly-recorded versions of his songs. Billie Holiday and Benny Carter collaborated to record “St. Louis Blues” and “Loveless Love”, but the other six sides were never recorded. It has been said that Billie didn’t like to record old standards, but I find her interpretation very deep and convincing. Backed by a marvelous ensemble including trumpeter Bill Coleman, trombonist Benny Morton and Carter on clarinet, she lays into the blue notes and swings magnificently. Count Basie’s sextet version from 1942 offers plenty of solo room for Buck Clayton’s trumpet, Don Byas’ tenor and the leader’s piano, but surprisingly for a Basie recording, the tempo never really gels. Unfortunately, these sides were recorded before a union recording strike and I suspect that Columbia was more interested in the quantity of sides rather the quality. Jack Teagarden’s Dixie-cum-Swing version dates from 1947 and finds a happy medium between the two styles. While the solos and Teagarden’s vocal echo the style of earlier jazz, the tidy arrangement hews to a small group swing model. Most of the jazz musicians in this era were employed in the big bands and played Dixie for their own enjoyment, so it was easy for  them to switch and mix the styles at will. Roy Eldridge’s 1944 version for three trumpets and rhythm was originally issued as “Little Jazz and His Trumpet Ensemble”. The tempo burns and Eldridge comes out breathing fire and smoke over Cozy Cole’s brushes. Joe Thomas stretches out his long lines over the surging rhythm, and after Johnny Guarnieri’s stride piano, Emmett Berry turns up the heat. Cozy Cole’s drum solo builds up to Eldridge’s scorching final chorus. Fats Waller’s rare solo version on electronic organ was recorded at his home just three months before his death. There’s no shortage of energy in Waller’s playing as he provides a mighty swing with the pedals and delightful variations on the manuals. [The YouTube video version linked above also includes his 1926 pipe organ solo and a piano solo from 1939.]

them to switch and mix the styles at will. Roy Eldridge’s 1944 version for three trumpets and rhythm was originally issued as “Little Jazz and His Trumpet Ensemble”. The tempo burns and Eldridge comes out breathing fire and smoke over Cozy Cole’s brushes. Joe Thomas stretches out his long lines over the surging rhythm, and after Johnny Guarnieri’s stride piano, Emmett Berry turns up the heat. Cozy Cole’s drum solo builds up to Eldridge’s scorching final chorus. Fats Waller’s rare solo version on electronic organ was recorded at his home just three months before his death. There’s no shortage of energy in Waller’s playing as he provides a mighty swing with the pedals and delightful variations on the manuals. [The YouTube video version linked above also includes his 1926 pipe organ solo and a piano solo from 1939.]

Earl Hines’ 1940 “Boogie Woogie on St. Louis Blues” was a hit record for his  big band. Hines maintains the boogie pattern for the first minute or so, then hints at it for the rest of the arrangement. Hines introduces his extended tremolo trick before returning to the boogie pattern for the coda. The band does not play very much on this side, and I suspect that George Dixon’s spoken comments were added to spice up the proceedings. While many Americans enjoyed the big bands of Earl Hines and his peers, they were not so happy to hear recordings by a group called “Charlie and his Orchestra”. Their records were produced in Berlin by the Nazi Party in an effort to sneak propaganda into Allied jukeboxes. The 78s were printed without label credits, and at the beginning of the sides, they sounded like typical big bands. However, the lyrics were filled with vile racism, and the Nazis thought that once the records had started playing on the jukebox, there would be no way to stop them. The version of “St. Louis Blues” features rather innocuous references to the Battle of Britain and Winston Churchill; later recordings in the series were much more offensive. American big bands were part of “the war effort” and in effect, tools of propaganda (although usually without “special lyrics”). Apart from its wartime connections, it’s impossible to regard Glenn Miller’s “St. Louis Blues March” as anything but a superbly played and arranged adaptation of the Handy classic. Propelled by a swinging snare drum march beat—could this be the genesis of “The Blues March”?—the piece strides along with a breezy air of confidence. And even though this recording was led by the most white-bread of all bandleaders, it was convincingly used at the conclusion of the film “A Soldier’s Story” to portray the black battalion’s pride in receiving their orders to enter combat.

big band. Hines maintains the boogie pattern for the first minute or so, then hints at it for the rest of the arrangement. Hines introduces his extended tremolo trick before returning to the boogie pattern for the coda. The band does not play very much on this side, and I suspect that George Dixon’s spoken comments were added to spice up the proceedings. While many Americans enjoyed the big bands of Earl Hines and his peers, they were not so happy to hear recordings by a group called “Charlie and his Orchestra”. Their records were produced in Berlin by the Nazi Party in an effort to sneak propaganda into Allied jukeboxes. The 78s were printed without label credits, and at the beginning of the sides, they sounded like typical big bands. However, the lyrics were filled with vile racism, and the Nazis thought that once the records had started playing on the jukebox, there would be no way to stop them. The version of “St. Louis Blues” features rather innocuous references to the Battle of Britain and Winston Churchill; later recordings in the series were much more offensive. American big bands were part of “the war effort” and in effect, tools of propaganda (although usually without “special lyrics”). Apart from its wartime connections, it’s impossible to regard Glenn Miller’s “St. Louis Blues March” as anything but a superbly played and arranged adaptation of the Handy classic. Propelled by a swinging snare drum march beat—could this be the genesis of “The Blues March”?—the piece strides along with a breezy air of confidence. And even though this recording was led by the most white-bread of all bandleaders, it was convincingly used at the conclusion of the film “A Soldier’s Story” to portray the black battalion’s pride in receiving their orders to enter combat.

In 1929, Bessie Smith made her only film appearance, and she sang “St. Louis Blues” with a large orchestra and chorus featuring James P. Johnson. As one of the earliest Harlem stride pianists, Handy’s song was probably a longtime part of Johnson’s repertoire. However, it was not until 1945 that he recorded a solo piano version. Most of the performance is in boogie-woogie style, and despite the fact that Johnson had suffered a stroke, his time and coordination are quite good for the first half of the recording (he rushes the tempo from then on). If it wasn’t for the tango section, we could hardly call this a version of “St. Louis Blues” at all. Johnson barely hints at the melody except at the beginning and end of the tango. Although there is another hint of the tune in one of the later blues choruses, it is such a generic idea that it could have come from another improvisation. Erroll Garner’s trio version was recorded in 1953, but it fits into this style period quite well. It is a particularly good introduction to Garner, as it offers the pianist’s elegant rhapsodic style in the opening choruses, a grandiose tango section that reappears at the coda and the romping “Garner strut” in the closing choruses. Mary Lou Williams embraced every new jazz style that came her way. Her 1944 solo piano version is predominantly a swing/boogie rendition, but the angular lines at the end of the introduction and in her final chorus hint at the bebop movement that was still developing at the time. Also noteworthy is Williams’ strong left hand that swings mightily even when she plays staccato notes in the bass.

When bebop dominated the jazz scene after World War II, it was met with  strong opposition from established musicians. Handy was one of bebop’s detractors and he tried (unsuccessfully) to stop the release of Dizzy Gillespie’s big band version. From its opening—borrowed from Charlie Parker’s modern blues “Parker’s Mood”—to its brash exposition of the melody, it’s easy to see why Handy disapproved. However, Gillespie’s version is an audacious translation of the standard into the language of bop. Arranger Budd Johnson maintained much of the Handy original in his treatment and supplemented it with the Gillespie spirit and style. In addition to Gillespie’s trumpet, there is an early example of a tenor player later known as Yusef Lateef. Gillespie and Mario Bauza had been friends since their time in Cab Calloway’s trumpet section, and both men were innovators in the fusion of Latin and bop styles. Bauza is the lead trumpeter on Machito’s brilliant Latin transformation of “St. Louis Blues”. The uncredited arrangement, which may be the work of Chico O’Farrill or Bauza himself, makes the Handy classic sound like it was meant to mambo, and the splendid execution of the parts by the horns and rhythm will make every listener want to dance. Babs Gonzales’ enthusiastic bop scatting enlivens his version of “St. Louis Blues”. Like Cab Calloway two decades before, Gonzales inserts new lyrics to talk about the women of New York City. While Gonzales was a through-and-through modernist, he brought in older players to fill out his recording groups. Here, Fletcher Henderson’s old arranger Don Redman plays soprano saxophone next to the young boppers Sonny Rollins and J.J. Johnson! This was Rollins’ second recording date, and his two-chorus solo showcases his penchant for sequencing and developing improvised ideas. Wynton Kelly was also new on the scene, and while he does not have a solo on this track, he was obviously having a lot of fun playing fills in the tango section. The Kenny Clarke/James Moody version was recorded in Paris, and aside from Moody’s humorous growling tenor on the melody, it is a straightforward modern jazz treatment. Moody displays his unique approach to improvised melody and rhythm, pianist Errol Parker shows an affinity for (if not the blazing technique of) Bud Powell, Pierre Michelot creates a fine horn-like bass solo, and Clarke matches every contrasting mood of his band mates.

strong opposition from established musicians. Handy was one of bebop’s detractors and he tried (unsuccessfully) to stop the release of Dizzy Gillespie’s big band version. From its opening—borrowed from Charlie Parker’s modern blues “Parker’s Mood”—to its brash exposition of the melody, it’s easy to see why Handy disapproved. However, Gillespie’s version is an audacious translation of the standard into the language of bop. Arranger Budd Johnson maintained much of the Handy original in his treatment and supplemented it with the Gillespie spirit and style. In addition to Gillespie’s trumpet, there is an early example of a tenor player later known as Yusef Lateef. Gillespie and Mario Bauza had been friends since their time in Cab Calloway’s trumpet section, and both men were innovators in the fusion of Latin and bop styles. Bauza is the lead trumpeter on Machito’s brilliant Latin transformation of “St. Louis Blues”. The uncredited arrangement, which may be the work of Chico O’Farrill or Bauza himself, makes the Handy classic sound like it was meant to mambo, and the splendid execution of the parts by the horns and rhythm will make every listener want to dance. Babs Gonzales’ enthusiastic bop scatting enlivens his version of “St. Louis Blues”. Like Cab Calloway two decades before, Gonzales inserts new lyrics to talk about the women of New York City. While Gonzales was a through-and-through modernist, he brought in older players to fill out his recording groups. Here, Fletcher Henderson’s old arranger Don Redman plays soprano saxophone next to the young boppers Sonny Rollins and J.J. Johnson! This was Rollins’ second recording date, and his two-chorus solo showcases his penchant for sequencing and developing improvised ideas. Wynton Kelly was also new on the scene, and while he does not have a solo on this track, he was obviously having a lot of fun playing fills in the tango section. The Kenny Clarke/James Moody version was recorded in Paris, and aside from Moody’s humorous growling tenor on the melody, it is a straightforward modern jazz treatment. Moody displays his unique approach to improvised melody and rhythm, pianist Errol Parker shows an affinity for (if not the blazing technique of) Bud Powell, Pierre Michelot creates a fine horn-like bass solo, and Clarke matches every contrasting mood of his band mates.

Metronome magazine was one of the top jazz periodicals from the 1930s  through the early 1960s. Each year, the magazine held a reader’s poll for an all-star band. The winners were gathered as an ensemble and they recorded a small group of sides together, with the proceeds going to charity. The 1953 band was an interesting mixture of swing, cool and bop players. Yet, despite these differences in style, they coalesced into an excellent group. Their version of “St. Louis Blues” was split over two sides of a disc, with Billy Eckstine heavily featured in the slow first half (with Lester Young and Roy Eldridge providing obbligatos), and most of the band featured in the fast jam in the second half. Max Roach kicks the tempo up for solos by Terry Gibbs, Kai Winding, Eckstine (scatting with Billy Bauer in support) and Young. After his solo, Eldridge leads the way out. Helen Humes, formerly with Count Basie, enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1950s. Her blistering fast “St. Louis Blues” features a splendid arrangement by Marty Paich and a top-notch big band with some of the best musicians working on the West Coast. At a time when the jazz recorded in California was being written off as bloodless, this performance shows that there was plenty of fire out west. Humes’ opening choruses contain lyrics from Handy’s original, but after solos by Art Pepper and Jack Sheldon, she introduces unique variations on standard blues stanzas. On paper, Jo Stafford’s version doesn’t make much sense: a blues recording with big band, strings, Latin percussion and background vocals. Yet, Stafford’s husband, Paul Weston, combines these disparate forces into a unified whole, and Stafford herself, through her earnest delivery and superb musicianship ties it all together. Neither Humes nor Stafford could be said to have the deep emotional impact of a Bessie Smith, but they weren’t aiming for that goal in the first place. Their versions display the universal appeal of Handy’s song and how it remained flexible for all sorts of interpretations.

through the early 1960s. Each year, the magazine held a reader’s poll for an all-star band. The winners were gathered as an ensemble and they recorded a small group of sides together, with the proceeds going to charity. The 1953 band was an interesting mixture of swing, cool and bop players. Yet, despite these differences in style, they coalesced into an excellent group. Their version of “St. Louis Blues” was split over two sides of a disc, with Billy Eckstine heavily featured in the slow first half (with Lester Young and Roy Eldridge providing obbligatos), and most of the band featured in the fast jam in the second half. Max Roach kicks the tempo up for solos by Terry Gibbs, Kai Winding, Eckstine (scatting with Billy Bauer in support) and Young. After his solo, Eldridge leads the way out. Helen Humes, formerly with Count Basie, enjoyed renewed popularity in the 1950s. Her blistering fast “St. Louis Blues” features a splendid arrangement by Marty Paich and a top-notch big band with some of the best musicians working on the West Coast. At a time when the jazz recorded in California was being written off as bloodless, this performance shows that there was plenty of fire out west. Humes’ opening choruses contain lyrics from Handy’s original, but after solos by Art Pepper and Jack Sheldon, she introduces unique variations on standard blues stanzas. On paper, Jo Stafford’s version doesn’t make much sense: a blues recording with big band, strings, Latin percussion and background vocals. Yet, Stafford’s husband, Paul Weston, combines these disparate forces into a unified whole, and Stafford herself, through her earnest delivery and superb musicianship ties it all together. Neither Humes nor Stafford could be said to have the deep emotional impact of a Bessie Smith, but they weren’t aiming for that goal in the first place. Their versions display the universal appeal of Handy’s song and how it remained flexible for all sorts of interpretations.

Big Joe Turner was closer to the soul of the blues, but his swinging 1956 version is as light-hearted as the Humes and Stafford versions. Recorded as Turner’s popularity was surging due to his connections with early rock and roll and R&B, the arrangement seems designed for dancing. The feel is very relaxed and Turner’s last two choruses—added spontaneously during the session—are delightful additions, even if they have no relation to Handy’s  original lyrics. Ella Fitzgerald was not a blues singer, and her 1963 album, “These Are The Blues” has been maligned by critics for many years. But it’s really not as bad as you might think. Her somber version of “St. Louis Blues” is closer to the spirit of the lyrics than many of the vocal recordings from this period, and she admirably communicates the sorrow of a rejected woman. When she deviates from Handy’s lyric, her words seem to continue the original narrative. Roy Eldridge, who toured with Fitzgerald during this period, offers a running commentary on trumpet with buzz mute, and Wild Bill Davis anchors the rhythm section on organ. As his career grew during the late 1950s, Jimmy Witherspoon surrounded himself with an all-star group of jazz musicians including Ben Webster, Gerry Mulligan and Jimmy Rowles. This powerfully swinging version was recorded at the Renaissance in Los Angeles, and it features Webster at his most passionate and Rowles at his wittiest. Witherspoon’s intense delivery peaks with his final two choruses which gives the St. Louis woman powers in voodoo and witchcraft.

original lyrics. Ella Fitzgerald was not a blues singer, and her 1963 album, “These Are The Blues” has been maligned by critics for many years. But it’s really not as bad as you might think. Her somber version of “St. Louis Blues” is closer to the spirit of the lyrics than many of the vocal recordings from this period, and she admirably communicates the sorrow of a rejected woman. When she deviates from Handy’s lyric, her words seem to continue the original narrative. Roy Eldridge, who toured with Fitzgerald during this period, offers a running commentary on trumpet with buzz mute, and Wild Bill Davis anchors the rhythm section on organ. As his career grew during the late 1950s, Jimmy Witherspoon surrounded himself with an all-star group of jazz musicians including Ben Webster, Gerry Mulligan and Jimmy Rowles. This powerfully swinging version was recorded at the Renaissance in Los Angeles, and it features Webster at his most passionate and Rowles at his wittiest. Witherspoon’s intense delivery peaks with his final two choruses which gives the St. Louis woman powers in voodoo and witchcraft.

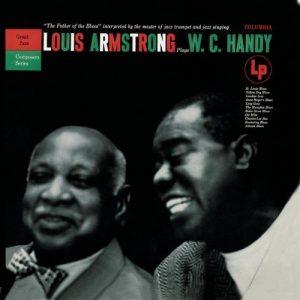

Webster’s former boss and his primary saxophone soloist, Duke Ellington and Johnny Hodges recorded “St. Louis Blues” as part of a blues-dominated set issued under Hodges’ name. Ellington sets the medium tempo with the rhythm section, and then Hodges and trumpeter Harry Edison bounce ideas back and forth through the exposition. Hodges loved to play the blues, and he digs deep for his choruses with swooping bent notes, his trademark creamy sound and a little grit in his attack. In the outer choruses of his solo, Edison makes the most out of minimal phrases, while opening up a little more in the middle of his statement. Ellington improvises a stark melodic line in his first chorus and contrasts it with chordal ideas in his second chorus. Hodges returns for a single chorus that seems rooted in big band riffs and then Edison joins him to  close with a powerful repeated motive. Louis Armstrong’s majestic 1954 version was the opening track of an album devoted to Handy’s music. When Handy came to the studio to listen to the session tapes with Armstrong, the now-blind composer was brought to tears by the arrangement and doubled over with laughter at Armstrong’s additional lyrics. One of those stanzas, regarding a picket fence, makes for uncomfortable listening today, but the rest of the performance is simply brilliant, from Armstrong’s resilient trumpet lead and his easy chemistry with vocalist Velma Middleton, to the fine supporting solos by Barney Bigard and Tyree Glenn.

close with a powerful repeated motive. Louis Armstrong’s majestic 1954 version was the opening track of an album devoted to Handy’s music. When Handy came to the studio to listen to the session tapes with Armstrong, the now-blind composer was brought to tears by the arrangement and doubled over with laughter at Armstrong’s additional lyrics. One of those stanzas, regarding a picket fence, makes for uncomfortable listening today, but the rest of the performance is simply brilliant, from Armstrong’s resilient trumpet lead and his easy chemistry with vocalist Velma Middleton, to the fine supporting solos by Barney Bigard and Tyree Glenn.

Miles Davis was born and raised in the St. Louis metropolitan area, but he never recorded a version of Handy’s paean to his hometown. Following the success of Davis’ collaboration with composer/arranger Gil Evans “Miles Ahead”, Evans recorded two albums for Pacific Jazz that presented his unique takes on revered jazz standards. The first of these albums featured alto saxophonist Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, who had recently joined Davis’ sextet. Since the albums moved chronologically through jazz history, the opening arrangement was, fittingly, “St. Louis Blues”. Adderley opens unaccompanied, displaying his rich and soulful sound, and when the band enters, we hear a fresh approach to instrumental voicing and abundant energy in the band. In fact, the listener might be so taken with Evans’ orchestration that he misses Adderley’s passionate delivery of the melody. In the tango, Evans layers a number of colors including guitar/piano/trumpet tremolos, parallel moving trombones, habanera rhythm in bass and drums and Adderley’s improvised alto. Few arrangers would have dared to include such a dense texture, but Evans makes it all work together. When the tempo picks up for Adderley’s solo, listen for a catchy background riff behind him and then marvel at how Evans develops it into a shout chorus. Dizzy Gillespie’s 1959 version is far less revolutionary than his big band version. In fact, he performed this version on a television show that same year. Gillespie performs a muted solo that is loaded with intensity, and Les Spann offers support to the leader with his stunning guitar commentary. The rhythm section opens up during Spann’s solo turn, which utilizes the parallel octave style later popularized by Wes Montgomery. Junior Mance’s funky piano leads to a Lex Humphries drum solo over the same clapping rhythm used in the introduction.

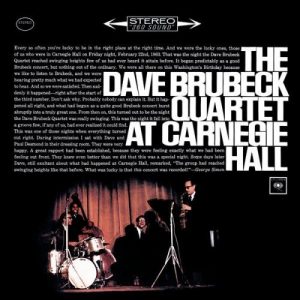

The Dave Brubeck Quartet was one of the most popular instrumental groups in jazz history. Its intellectual, yet passionate approach to modern jazz was embraced by college-educated listeners, many of whom first heard the group during a series of college concerts in the early 50s. Brubeck opened nearly all of his concerts with “St. Louis Blues”, as it proved to be an excellent vehicle to establish the evening’s mood. This was especially true at their Carnegie Hall concert in 1963. The performance starts in the song’s original key of G major, but when alto saxophonist Paul Desmond enters for his solo, the key abruptly changes to E-flat. Desmond’s wistfully cool alto sails through thirteen choruses as the swing deepens in the rhythm section. Brubeck modulates back to G and then yields for Gene Wright’s bass solo, which ends with the unusual note choice of an E natural. Brubeck picks up the note and before long, he is playing in E with his left hand and in G with his right! While Brubeck had played polytonally before, this was the first time he had improvised with this particular key relationship. His solo is also notable for his keen development and expansion of his improvised ideas. While his days of being a classical composer were still ahead of him, he was honing those skills on the bandstand. Joe Morello plays a brief but exciting drum solo after Brubeck, and his solo makes for an interesting comparison with the percussionist on the next track, Max Roach. Roach’s “St. Louis Blues” was recorded in 1965 with the obscure soprano saxophonist Roland Alexander, the unfairly neglected alto saxophonist James Spaulding and the much better-known trumpeter Freddie Hubbard. Roach’s arrangement is a kaleidoscope of varying tempos and meters, starting in waltz time, moving to a faster three-beat and then to a burning fast 4/4 for the main solos. Alexander has superb control over the straight horn and a flood of inspired ideas, Hubbard spices up his work with sharp-edged growls and Spaulding displays an excellent concept of time. Roach, who was an expert at quick tempos, creates a stunning solo that mixes brilliant technique with his own melodic approach to percussion.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet was one of the most popular instrumental groups in jazz history. Its intellectual, yet passionate approach to modern jazz was embraced by college-educated listeners, many of whom first heard the group during a series of college concerts in the early 50s. Brubeck opened nearly all of his concerts with “St. Louis Blues”, as it proved to be an excellent vehicle to establish the evening’s mood. This was especially true at their Carnegie Hall concert in 1963. The performance starts in the song’s original key of G major, but when alto saxophonist Paul Desmond enters for his solo, the key abruptly changes to E-flat. Desmond’s wistfully cool alto sails through thirteen choruses as the swing deepens in the rhythm section. Brubeck modulates back to G and then yields for Gene Wright’s bass solo, which ends with the unusual note choice of an E natural. Brubeck picks up the note and before long, he is playing in E with his left hand and in G with his right! While Brubeck had played polytonally before, this was the first time he had improvised with this particular key relationship. His solo is also notable for his keen development and expansion of his improvised ideas. While his days of being a classical composer were still ahead of him, he was honing those skills on the bandstand. Joe Morello plays a brief but exciting drum solo after Brubeck, and his solo makes for an interesting comparison with the percussionist on the next track, Max Roach. Roach’s “St. Louis Blues” was recorded in 1965 with the obscure soprano saxophonist Roland Alexander, the unfairly neglected alto saxophonist James Spaulding and the much better-known trumpeter Freddie Hubbard. Roach’s arrangement is a kaleidoscope of varying tempos and meters, starting in waltz time, moving to a faster three-beat and then to a burning fast 4/4 for the main solos. Alexander has superb control over the straight horn and a flood of inspired ideas, Hubbard spices up his work with sharp-edged growls and Spaulding displays an excellent concept of time. Roach, who was an expert at quick tempos, creates a stunning solo that mixes brilliant technique with his own melodic approach to percussion.

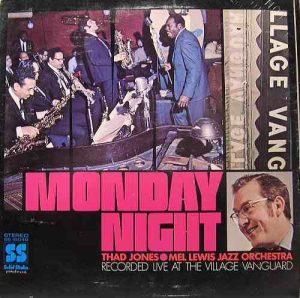

The Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra started as a rehearsal band in  1965. The next year, it started a tradition of playing on Monday nights at the Village Vanguard, and that tradition continues to this day, surviving the death of both of its leaders and ongoing personnel shifts. While much of the band’s repertoire was contributed by Jones (a superb arranger whose unique approach to instrumentation and voicing became as influential as Gil Evans), many of the band’s earliest charts were written by valve trombonist Bob Brookmeyer. By the time the band recorded Brookmeyer’s elaborate chart on “St. Louis Blues” in October 1968, the trombonist had left the group for an extended stay in California. Brookmeyer’s arrangement opens with an original blues melody which is followed by an eerie, hollow-sounding voicing of the Handy melody. Brookmeyer’s introduction returns behind Jones, and Handy’s melody reappears in the midst of Garnett Brown’s trombone solo. Throughout the work, Brookmeyer varies the backgrounds behind the soloists, and also gives some of them the opportunity to play unaccompanied. The a cappella solo section also proves to be an effective segue between soloists as Jerome Richardson takes the solo spotlight from Brown. The opening choruses of Jones’ solo are backed with a funky two-beat background. After the backgrounds move into a straight-ahead 4/4, there is another sudden shift in soloists as Roland Hanna plays a very traditional sounding piano solo which effectively contrasts with the return of Brookmeyer’s original melody.

1965. The next year, it started a tradition of playing on Monday nights at the Village Vanguard, and that tradition continues to this day, surviving the death of both of its leaders and ongoing personnel shifts. While much of the band’s repertoire was contributed by Jones (a superb arranger whose unique approach to instrumentation and voicing became as influential as Gil Evans), many of the band’s earliest charts were written by valve trombonist Bob Brookmeyer. By the time the band recorded Brookmeyer’s elaborate chart on “St. Louis Blues” in October 1968, the trombonist had left the group for an extended stay in California. Brookmeyer’s arrangement opens with an original blues melody which is followed by an eerie, hollow-sounding voicing of the Handy melody. Brookmeyer’s introduction returns behind Jones, and Handy’s melody reappears in the midst of Garnett Brown’s trombone solo. Throughout the work, Brookmeyer varies the backgrounds behind the soloists, and also gives some of them the opportunity to play unaccompanied. The a cappella solo section also proves to be an effective segue between soloists as Jerome Richardson takes the solo spotlight from Brown. The opening choruses of Jones’ solo are backed with a funky two-beat background. After the backgrounds move into a straight-ahead 4/4, there is another sudden shift in soloists as Roland Hanna plays a very traditional sounding piano solo which effectively contrasts with the return of Brookmeyer’s original melody.

The Dave Brubeck/Marian McPartland version comes from an episode of McPartland’s long-running public radio series “Piano Jazz”. McPartland was an established piano voice when she started the show in 1978, but with her exposure to a wide variety of pianists who were guests on the show came a deepening sense of style and conviction, even as she approached her 93rd birthday. She was always a gracious host and let her guests lead the way in piano duets. Brubeck, whose style had become less percussive and more subtle over the years, plays solo for the first several minutes of this duet, displaying a modified stride style, rich polytonality, and several surprising improvised ideas. After he verbally encourages McPartland to join him, she becomes a vital partner in the duet, taking chances and developing unusual ideas of her own. When the two join forces for a rocking variation, it sounds like the arrangement is coming to an end, but there are plenty more surprises in store, including an impressionistic take on the tango section and a gradually building variation built on the triplets introduced by McPartland a few minutes  earlier. The Cleo Laine/John Dankworth version from the 1991 album “Jazz” is one of Laine’s finest later efforts, and comes highly recommended. While Dankworth’s arrangement of “St. Louis Blues” is tightly crafted, it is loose enough to allow the performers room for interpretation. Laine, a versatile performer with an astonishing range, gets to display her expertise in each part of her voice, use her voice as an instrument and exchange improvised thoughts with Dankworth. The exuberant performance swings even in the funk sections and the band transitions effortlessly between the funk and straight-ahead jazz episodes. And, in a master stroke of arranging technique, Dankworth spreads out the exposition of the melody throughout the length of the arrangement.

earlier. The Cleo Laine/John Dankworth version from the 1991 album “Jazz” is one of Laine’s finest later efforts, and comes highly recommended. While Dankworth’s arrangement of “St. Louis Blues” is tightly crafted, it is loose enough to allow the performers room for interpretation. Laine, a versatile performer with an astonishing range, gets to display her expertise in each part of her voice, use her voice as an instrument and exchange improvised thoughts with Dankworth. The exuberant performance swings even in the funk sections and the band transitions effortlessly between the funk and straight-ahead jazz episodes. And, in a master stroke of arranging technique, Dankworth spreads out the exposition of the melody throughout the length of the arrangement.

While the Cleo Laine recording closes the compilation, it is far from the end of the “St. Louis Blues” story. Several noteworthy versions have appeared in the past two decades, including an Anat Cohen version reviewed elsewhere on this site. As “St. Louis Blues” approaches its centenary, it still inspires new versions and interpretations. What a legacy for a southern preacher, a downhearted woman and a young composer.

The audio recordings embedded in this article are presented for educational and illustrative purposes. Jazz History Online neither owns nor controls the rights to these recordings. All rights belong to the original copyright holders.