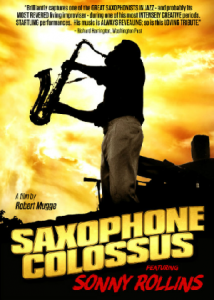

Near the end of the 1986 documentary on Sonny Rollins, “Saxophone Colossus”, Rollins’ wife and manager Lucille states that the saxophonist was playing better than ever. Judging by the music contained within the film, it is hard to disagree. While a trio of jazz critics and Rollins himself discuss the earlier parts of his career, most of Robert Mugge’s feature-length film deals with Sonny Rollins in the (then) present tense. Viewers looking for extensive discussions of classic Rollins albums like “Way Out West”, “The Freedom Suite” and “A Night at the Village Vanguard” will be disappointed by this film. However, Rollins’ legacy as a great jazz improviser depends on the continuing development of his craft, and viewers who appreciate that simple truth will understand the film’s main purpose.

Near the end of the 1986 documentary on Sonny Rollins, “Saxophone Colossus”, Rollins’ wife and manager Lucille states that the saxophonist was playing better than ever. Judging by the music contained within the film, it is hard to disagree. While a trio of jazz critics and Rollins himself discuss the earlier parts of his career, most of Robert Mugge’s feature-length film deals with Sonny Rollins in the (then) present tense. Viewers looking for extensive discussions of classic Rollins albums like “Way Out West”, “The Freedom Suite” and “A Night at the Village Vanguard” will be disappointed by this film. However, Rollins’ legacy as a great jazz improviser depends on the continuing development of his craft, and viewers who appreciate that simple truth will understand the film’s main purpose.

The first half of the film spotlights Rollins with his combo at an outdoor concert in upstate New York. Rollins opens things up with a marathon solo on his original “G-Man”. The song is based on a single repeated motive, and the harmonies seem to alternate between two chords. Of course, that is all the framework Rollins needs to create and develop a multitude of ideas. But in seeing and hearing this performance again after several years, I was amazed not only at Rollins’ endless creativity, but also how well his band responded to him. As is his wont, Rollins will return for a theme statement in the midst of a long improvisation; yet it is never entirely clear just when (or if) that will happen. Rollins’ band listens intently to each nuance of his solo in order to spontaneously react to an idea or to follow him into another theme statement. This working band—Clifton Anderson (trombone), Mark Soskin (piano), Bob Cranshaw (electric bass), and Marvin “Smitty” Smith (drums)—received many critical brickbats in their heyday, but their amazing performance on “G-Man” (and later in the film, “Don’t Stop the Carnival”) shows us why Rollins continued to work and develop this particular band. A few minutes after this performance, critic Francis Davis makes the surprising comment that Rollins “never created a band in his image”. I think that Rollins’ 1986 group was precisely that band.

Mugge’s film is best-known for capturing an audacious Rollins stunt. In the midst of an unaccompanied improvisation, the saxophonist leaped off of a sculpted rock stage to a landing about six feet below. Rollins had misjudged the steepness and depth of the drop, and landed on his back, breaking his heel in the process. After a few seconds of silence, Rollins put his horn back in his mouth and started to play again (to the great relief of the musicians, film crew, and doubtlessly Lucille). When he interviewed Rollins a few weeks later, Mugge asked about the leap and Rollins—now sporting a foot cast—explained that it was a spontaneous, and not too wise, decision to add a visual element to the performance. However, in a new supplemental feature for this home video release, Mugge now says that Rollins’ leap was an act of desperation, stemming from an unresponsive (and newly lacquered) horn. Ironically, Rollins talked about that element too in the documentary—not precisely about the lacquer job, but his frustration when his horn doesn’t follow his bidding.

At the midway point, the film moves to Japan for the premiere of Rollins’ original concerto for tenor saxophone and orchestra. Rollins’ work is similar in concept to the Stan Getz/Eddie Sauter collaboration, “Focus”. Both pieces are multi-movement works with a primarily improvised saxophone part. The juxtaposition of straight classical style in the orchestra versus the free improvisation of the saxophone soloist is the primary characteristic of both works. While Getz had no input on Sauter’s compositions (the string parts were designed to stand on their own without the soloist), Rollins composed all of themes and motives in his concerto, leaving the organization and orchestration to Finnish composer/conductor/pianist Heikki Sarmanto. As a whole, I don’t find the Rollins concerto terribly compelling. However, Mugge’s use of footage of Japanese citizens and scenery enhances Rollins’ music, much in the same way that Ernie Kovacs envisioned the music of lounge bandleader Esquivel. Both Kovacs and Mugge found ways to create visual counterpoint with the music through the use of elements common to both mediums: rhythm, tempo, and shapes (phrase shapes in music; literal shapes for visuals). It isn’t that Rollins’ concerto is especially Japanese—despite being commissioned, rehearsed and premiered in Japan—but that Mugge found Japanese images that matched the moods of Rollins’ music. In the same supplemental interview, Mugge reveals the reason for the external Japanese footage: his limited budget only allowed him to bring two cameramen and a sound man to film the concerto. The B-roll footage was made to fill in visual gaps in the concert. Like Rollins’ leap from the stone stage, Mugge created something highly memorable from a negative occurrence.

MVD’s DVD and Blu-Ray present “Saxophone Colossus” in a new 4K restoration. Most of the titles have been remade (with a new dedication to the late Lucille Rollins), the sound is a clear 2-channel Dolby Digital mix, and the orchestra concert features greatly improved images. All of the outdoor footage, including the New York concert and all of the interviews, is still rather grainy, and at least one of the interviews with Sarmanto shows some wear and damage. The one archival clip, from Rollins’ 1962 appearance on “Jazz Casual”, is tinted and lacks definition (was Mugge unable to secure a fresh copy of the clip from Ralph J. Gleason’s estate?) Despite these minor—and possible unavoidable—flaws, it is good to see this fine documentary available again on home video.