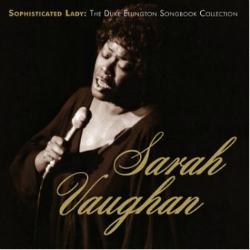

Sometimes the jazz critics get it right. In 1978, Gary Giddins reviewed Sarah Vaughan’s LP “How Long Has This Been Going On” for the Village Voice. He suggested that if producer Norman Granz would “parade the entire Pablo stock company through [Vaughan’s] sessions (including, one hopes, a set of Benny Carter arrangements), he will be mining the most valuable lode since Ella Fitzgerald discovered songbooks”. Starting in August of the next year, Granz did just that: he produced Vaughan’s “Duke Ellington Songbook” featuring guest appearances by several of Pablo’s star roster and—in its original conception—six arrangements by Benny Carter. The Carter session was not issued at the time and it now appears for the first time on Concord’s new CD reissue of the albums, re-titled “Sophisticated Lady: The Duke Ellington Songbook Collection“. The original LPs were issued as two separate volumes without liner notes or complete personnel listings. Granz jumbled the tracks to spread the big band, orchestral and small group tracks over the four LP sides. Concord has straightened out this entire mess by commissioning notes by Granz biographer Tad Hershorn, and sequencing the tracks in chronological session order. This places the Carter session at the beginning of the set and leaves the exquisite trio set (with Vaughan, pianist Mike Wofford and guitarist Joe Pass) at the end.

Sometimes the jazz critics get it right. In 1978, Gary Giddins reviewed Sarah Vaughan’s LP “How Long Has This Been Going On” for the Village Voice. He suggested that if producer Norman Granz would “parade the entire Pablo stock company through [Vaughan’s] sessions (including, one hopes, a set of Benny Carter arrangements), he will be mining the most valuable lode since Ella Fitzgerald discovered songbooks”. Starting in August of the next year, Granz did just that: he produced Vaughan’s “Duke Ellington Songbook” featuring guest appearances by several of Pablo’s star roster and—in its original conception—six arrangements by Benny Carter. The Carter session was not issued at the time and it now appears for the first time on Concord’s new CD reissue of the albums, re-titled “Sophisticated Lady: The Duke Ellington Songbook Collection“. The original LPs were issued as two separate volumes without liner notes or complete personnel listings. Granz jumbled the tracks to spread the big band, orchestral and small group tracks over the four LP sides. Concord has straightened out this entire mess by commissioning notes by Granz biographer Tad Hershorn, and sequencing the tracks in chronological session order. This places the Carter session at the beginning of the set and leaves the exquisite trio set (with Vaughan, pianist Mike Wofford and guitarist Joe Pass) at the end.

The revised track sequence also provides clues about why the Carter session was left unissued. In 1979, Sarah Vaughan was a newlywed, and her new husband was trumpeter Waymon Reed. Reed was a competent (if not startlingly original) musician, and Vaughan wanted to give him plenty of solo space on her new records. As Hershorn relates the story, Granz had ignored her request to feature Reed, and Carter’s orchestral arrangements featured the tenor sax of Zoot Sims instead. I can’t believe that this is the whole story. Carter could have easily adapted his arrangements to include solos by Reed, and if Reed wasn’t at the studio that day, he could have overdubbed the solos later. As Hershorn states elsewhere in the notes, Granz had run into a similar problem 21 years earlier when Ellington decided to adapt his existing band charts instead of creating new settings for Ella Fitzgerald’s Ellington songbook. But in Vaughan’s case, no concession was made, and the real loser was Benny Carter. There was nothing really wrong with Carter’s settings, but Vaughan’s performances of them are rough and loose. With a few retakes, they might have been suitable for initial release, but Vaughan must have known she could do better. Two days later, she re-recorded three of the songs from the Carter session with a small group, and these recordings reveal a newly energized and focused Vaughan in renditions that easily surpass the Carter versions. The difference was Reed, who was featured on the next five sessions for the album. He doesn’t play on every track, but his solos are well-constructed and stand up well against the session’s better-known soloists Frank Wess, J.J. Johnson, Jimmy Rowles, Pass and Sims. Vaughan is clearly inspired by Reed’s presence, as his plunger muted trumpet helps her build “I’m Just A Lucky So-And-So” to an ecstatic climax. But the best evidence of their musical and personal chemistry comes in the preceding track, “What Am I Here For”, where Vaughan and Reed perform a delightful dual improvisation where the lines perfectly complement one another.

One of the highlights of the set is the Billy Byers-led big band session that opens disc 2. On “I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart”, Vaughan is in complete rhythmic synchronicity with the band, she knows the way that the arrangement develops, and in the second chorus she presages one of Byers’ ensemble figures with her improvised variation “Come back, music”. She is no less impressive on the Ducal rarity “Black Butterfly” where she mixes her rich voice and her exquisite rhythmic sense to lift the song away from its mournful lyrics. “It Don’t Mean A Thing” features a brilliant scat solo over a superbly crafted arrangement. Vaughan returned to the studios the next day for another session with Byers, this time with Reed and a string orchestra. The new version of “In a Sentimental Mood” is glorious, as is the performance of “I Got It Bad”. On both, Vaughan’s voice is like slow-dripping honey and her variations on the original melodies rank with her best work. The vocal performances of the other two titles, “Lush Life” and “Tonight I Shall Sleep” are better than the Carter versions, but Carter’s arrangements of these songs are much better than Byers’. Carter’s setting of “Lush Life” stays in the same tempo throughout, and avoids the temptation—as Byers apparently could not—of illustrating every line of the text (If I hear one more arrangement of this song with a pseudo-blues lick after the words “jazz and cocktails”, I may go ballistic!). Byers’ setting of “Tonight I Shall Sleep” is a bossa that veers very close to Muzak. The next session is a near misfire. The only released track is a version of “Rocks In My Bed” with guest Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson and a small blues combo. Ellington wrote a pair of contrasting melodies for this blues, but Vaughan—who may not have had a lead sheet—only sings the first verse. About halfway through the performance, there is a sudden modulation for Vinson’s raw alto sax. Later, he sings a few blues stanzas with no connection to Ellington, and the only thing that saves the track is Vaughan’s hummed and sung responses. The set closes with the aforementioned trio set, with a lovely “Prelude to a Kiss”, a sly “Everything but You” and a stunning “I Ain’t Got Nothin’ but the Blues” featuring stark a cappella choruses by Vaughan.

Like her other marriages, Vaughan’s union with Reed was short-lived. They were divorced iin 1981 and two years later, Reed died of cancer. He never became the major soloist that he and Vaughan dreamed of, but he was an important catalyst for Vaughan’s Ellington albums. We don’t know if Reed was in the studio on the days he didn’t record, but his presence on the other five sessions helped Vaughan create a late-career masterpiece. Gary Giddins may have been right in predicting the album’s content, but Sarah Vaughan was right in featuring her inspiration.