The typical reaction to jazz on film or television is reminiscent of the classic Borscht belt joke:

CUSTOMER 1: The food at this restaurant is terrible!

CUSTOMER 2: Yes! And such small portions!

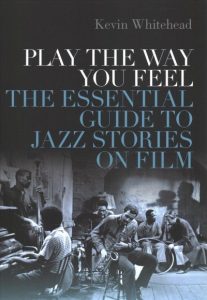

In other words, jazz is not properly treated in mass media, and why isn’t there more of it? One basic reason why jazz is a rarity onscreen is there are not enough fans to support the finished product, either through ticket sales or commercial revenue. To reap the high profits required for mass media, writers and producers have to make the subject appeal to a wider (read: non-jazz) audience. That process usually involves adding embellishments or fabrications to a jazz-based story. However, jazz films and TV shows do get things right on occasion, and the creators deserve credit when offering the facts, and chides when they present outright fiction. Kevin Whitehead’s new book “Play the Way You Feel” (Oxford) discusses the history of jazz biopics and fiction films, giving readers an entertaining mix of cheers and jeers to a wide cross-section of films.

Whitehead’s book is arranged chronologically, starting with “The Jazz Singer”  (1927) and ending with “Bolden” (2019). Along the way, he discusses virtually every important jazz feature (but purposely excludes performance and documentary films). Whitehead begins with the notorious Al Jolson picture, not to brand Jolson as a jazz vocalist—he wasn’t, although Whitehead praises Jolson’s whistling—but to focus on the movie’s themes, many of which (sacred vs. secular, racial relations, artistic passion) recur in later films. These tropes and others—the push and pull between jazz and classical styles, the girlfriend who doesn’t understand jazz until halfway through the picture, and the inevitable concert finale which reunites the feuding principals—are traced throughout the narrative, which at its essence, is a collection of movie synopses.

(1927) and ending with “Bolden” (2019). Along the way, he discusses virtually every important jazz feature (but purposely excludes performance and documentary films). Whitehead begins with the notorious Al Jolson picture, not to brand Jolson as a jazz vocalist—he wasn’t, although Whitehead praises Jolson’s whistling—but to focus on the movie’s themes, many of which (sacred vs. secular, racial relations, artistic passion) recur in later films. These tropes and others—the push and pull between jazz and classical styles, the girlfriend who doesn’t understand jazz until halfway through the picture, and the inevitable concert finale which reunites the feuding principals—are traced throughout the narrative, which at its essence, is a collection of movie synopses.

Whitehead takes a light tone with all of this material, but he demands that his readers pay close attention to his words. It may be tempting for a reader to skim through a 10-page description of a film he or she has not seen, but Whitehead has no patience with that: he constantly compares the main characters of his current film to ones in earlier chapters. Readers who fail to pay attention throughout will miss half of the author’s points. When read with the proper amount of concentration, Whitehead’s essays lead to a list of remarkable films, pointing out their strengths and weaknesses, which should encourage readers to seek out the films they have missed. Thankfully, there is no need to keep a pen and notepad by the book; every film discussed in the text appears in boldface within the index (Nice touch, Oxford).

Even if Hollywood doesn’t always get it right, Whitehead does. His assessment of Bessie Smith’s performance in the 1929 short, “St. Louis Blues” perfectly captures her astounding screen presence and heartfelt vocals. When he writes of the 1958 “St. Louis Blues”—a largely fictional biography of W.C. Handy—he first summarizes Handy’s autobiography, “Father of the Blues” and after discussing several vivid episodes from Handy’s career, he writes that a movie version of the book practically writes itself, but there’s barely a whiff of that in the actual [film]. Then he states why: A more faithful version would have cost much more and would confront racial issues this film ducks. He uses a brief section on Billy Wilder’s “Some Like it Hot” to discuss jazz’s other underused population, women instrumentalists, telling us about films by outstanding all-female groups including The Ingenues and International Sweethearts of Rhythm. In later years, jazz films have adopted elliptical, non-linear storytelling, and Whitehead’s commentary helps guide viewers through films like “Bird”, “Round Midnight”, “Miles Ahead” and “Bolden”. He has little patience for Damien Chazelle’s films, finding J.K. Simmons’ character in “Whiplash” unnecessarily brutal, and later questioning Ryan Gosling’s motives in “La La Land”. I wish that Whitehead would have included a few more foreign films in his study (Miles Davis’ improvised score to “Elevator to the Gallows” deserves mention if only for raising the overall quality of a non-jazz film). However, this book has much to recommend it, and I suspect that I will refer back to it many times in the coming years.

Whitehead’s focus on filmed fiction and biographies necessarily omitted one series that did get jazz right. “Stars of Jazz” was a fairly successful LA-based TV series featuring famous and obscure jazz musicians, who were playing at local clubs. The show did right by the musicians, playing union scale and treating their music with respect. Host Bobby Troup eschewed the usual jive-talking announcements, and replaced them with highly intelligent introductions which sometimes echoed the stage patter of Stan Kenton. The set included a rear projection system for album covers and background art, and the producers also found unique visual ideas to accompany the music (animated films, shots of flowing water, and an oscilloscope screen). The series was a critical success, winning accolades and award, including an Emmy. In the first weeks of the series, there were no ratings reports for the show, and there was minimal feedback from viewers. The station nearly cancelled the show for lack of audience, so the producers took a gamble: at the end of the third episode, Troup offered a free jazz book to any viewers who would send a post card to the station. Thousands of cards flowed in, far outnumbering the supply of books, and the show remained on the air. The series lasted three years, and appeared on the ABC-TV national network for its last few months. James A. Harrod’s study, “Stars in Jazz” (McFarland) offers a show-by-show history of the series, which is a considerable feat in that only about 50 of the series’ 130 episodes have survived.

Whitehead’s focus on filmed fiction and biographies necessarily omitted one series that did get jazz right. “Stars of Jazz” was a fairly successful LA-based TV series featuring famous and obscure jazz musicians, who were playing at local clubs. The show did right by the musicians, playing union scale and treating their music with respect. Host Bobby Troup eschewed the usual jive-talking announcements, and replaced them with highly intelligent introductions which sometimes echoed the stage patter of Stan Kenton. The set included a rear projection system for album covers and background art, and the producers also found unique visual ideas to accompany the music (animated films, shots of flowing water, and an oscilloscope screen). The series was a critical success, winning accolades and award, including an Emmy. In the first weeks of the series, there were no ratings reports for the show, and there was minimal feedback from viewers. The station nearly cancelled the show for lack of audience, so the producers took a gamble: at the end of the third episode, Troup offered a free jazz book to any viewers who would send a post card to the station. Thousands of cards flowed in, far outnumbering the supply of books, and the show remained on the air. The series lasted three years, and appeared on the ABC-TV national network for its last few months. James A. Harrod’s study, “Stars in Jazz” (McFarland) offers a show-by-show history of the series, which is a considerable feat in that only about 50 of the series’ 130 episodes have survived.

Harrod scoured the files of the LA musician’s union to discover the full personnel and repertoire of every group which appeared on the show. He found scripts and production notes at the LA Jazz Institute, and discovered several critiques and summaries of the show in local newspapers and magazines. He even tracked down biographical information on the many obscure jazz singers who appeared on the show. For that work alone, Harrod’s book is a valuable resource that belongs in the libraries of public institutions and jazz lovers. Unfortunately, the remainder of the text leaves much to be desired. How is it possible to miss the well-known fact that Barney Bigard played for years with Louis Armstrong after leaving Duke Ellington? (Harrod’s narrative would have you believe that the clarinetist only played with Freddie Slack and in the studios post-Duke. Has he not heard “Louis Armstrong Plays W.C. Handy”?!) In discussing Abbey Lincoln’s appearance on the show, Harrod goes into a paragraph-long discussion of other pianists who accompanied vocalists who didn’t bring their own, but he never mentions Lincoln’s pianist, Phil Wright! The circumstances Harrod gives for the eventual cancellation of “Stars of Jazz” are murky at best, and he never makes his own comparisons of “Stars of Jazz” with other jazz shows. In essence, Harrod reverses but never answers the old joke: “Stars of Jazz” was very good, but why such small portions?