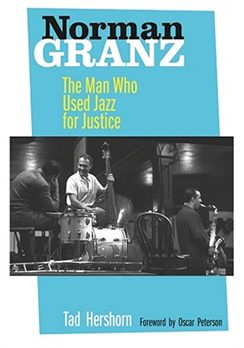

If you wanted to write a jazz biography, you could hardly find a more difficult subject than Norman Granz. Notoriously brusque, with a strong dislike for jazz writers, Granz abandoned an autobiography several years ago, and only gave author Tad Hershorn limited information about his life and career. Nonetheless, Hershorn’s biography, “Norman Granz: The Man Who Used Jazz for Justice” (University of California Press), is a well-researched history of this self-made jazz producer and impresario.

If you wanted to write a jazz biography, you could hardly find a more difficult subject than Norman Granz. Notoriously brusque, with a strong dislike for jazz writers, Granz abandoned an autobiography several years ago, and only gave author Tad Hershorn limited information about his life and career. Nonetheless, Hershorn’s biography, “Norman Granz: The Man Who Used Jazz for Justice” (University of California Press), is a well-researched history of this self-made jazz producer and impresario.

Granz was not a musician, but his efforts to promote the music through his Jazz at the Philharmonic concerts, and the myriad recordings produced under his supervision changed the methods and expectations for how jazz was presented. Put simply, he became a millionaire completely by promoting jazz. Yet, Granz paid his musicians better than anyone else, treated them at premiere hotels and restaurants, and offered financial support to musicians in need. He had a long-standing intolerance of racial segregation, and canceled concerts if he spotted bigoted attitudes among the management or audiences. He claimed to never tell a musician how to play, but the honking tenor saxes and screaming trumpets at the JATP concerts often led to wild audiences and musical cacophony (the word “circus” is quoted several times in Hershorn’s book to describe JATP jam sessions). The success of the JATP live recordings led Granz to start his own record companies, and it could be argued that the best music Granz produced was created in the studio. Through recordings on his labels Clef, Norgran, Verve and Pablo, Granz produced dozens of albums by the musicians he loved, including Art Tatum, Oscar Peterson, Count Basie, Roy Eldridge, Zoot Sims, Stan Getz, Joe Pass, Lester Young, Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald.

Granz did more for Fitzgerald than anyone else. He featured her in JATP, where her imaginative scatting made her a crowd favorite and a peer amongst musicians. When he became her personal manager, he booked her into venues that were not only new to Fitzgerald, but to black entertainers in general. After a long struggle, Granz obtained Fitzgerald’s release from Decca Records. He launched Verve to feature Fitzgerald, starting the “Song Book” series that transformed her into a world-class vocalist, and releasing a plethora of non-songbook recordings that displayed her versatility in a wide variety of live and studio settings. Granz also spearheaded the career of Oscar Peterson, and continued managing both Fitzgerald and Peterson after he sold Verve in 1960 and moved to Geneva.

Hershorn covers all of the aspects of Granz’ career in sharp detail. He is not afraid to question the judgment of his subject, or to specify when Granz made a particularly wrong turn. Although Granz’ concert and recording activities tended to dovetail, Hershorn wisely separates them to keep his story clear. Unfortunately, Hershorn also previews some of the incidents of Granz’ life and then returns to them a few pages later. This causes unnecessary confusion to the reader. For example, on page 381, Hershorn tells us of Granz’ writing large checks to friends in 2000 after learning that he had cancer. The narrative then moves onto his friendships with Clark Terry and John McDonough, and his relationship with his wife, Grete, before returning to the cancer and its effects on Granz on page 384. I suspect that the problem may be with the editing of the book rather than Hershorn’s contribution, but regardless of who is at fault, this odd structuring of the story weakens an otherwise fine book.

The end matter includes a chronology, footnotes, a bibliography and index, but no discography. This seems a major oversight, in that Granz’ legacy is largely documented in the recordings he produced. Hershorn states that Granz seemed ambivalent about his standing in jazz history, but ultimately, that is the job of historians and listeners, and the best way to appreciate the work of Norman Granz is to listen to the music he presented to the world.