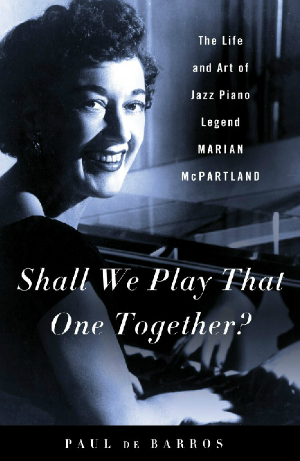

Marian McPartland is a survivor. At 95, she has outlived her contemporaries, and has only recently retired from performing and broadcasting. Her long career has shown steady growth as performer, both in technique and depth. She frequently referred to the interaction with her guests on NPR’s “Piano Jazz” as “getting a piano lesson”, and her infectious joy of learning was one of that show’s greatest features. Yet there is more to McPartland than just a genteel personality with abundant enthusiasm and a strong musical identity. Through the superb film documentary “In Good Time” and Paul de Barros’ new McPartland biography, “Shall We Play That One Together” (St. Martin’s), we’ve learned that she is also a tough-minded businesswoman and a demanding artist, with a weakness for dirty jokes.

Marian McPartland is a survivor. At 95, she has outlived her contemporaries, and has only recently retired from performing and broadcasting. Her long career has shown steady growth as performer, both in technique and depth. She frequently referred to the interaction with her guests on NPR’s “Piano Jazz” as “getting a piano lesson”, and her infectious joy of learning was one of that show’s greatest features. Yet there is more to McPartland than just a genteel personality with abundant enthusiasm and a strong musical identity. Through the superb film documentary “In Good Time” and Paul de Barros’ new McPartland biography, “Shall We Play That One Together” (St. Martin’s), we’ve learned that she is also a tough-minded businesswoman and a demanding artist, with a weakness for dirty jokes.

Drawing on published and original interviews with McPartland, her family, friends, colleagues and occasional enemies, de Barros paints a vivid picture of the pianist’s life and career. He quotes several letters from McPartland’s personal archive. More than most jazz biographies, we learn several intimate details about the subject’s personal life (de Barros even takes a chapter-long detour to offer a biography of McPartland’s long-time husband, cornetist Jimmy McPartland). But de Barros’ biggest bombshell is a discussion of McPartland’s decade-long extramarital affair with drummer Joe Morello. Clearly, McPartland gained most of her early popularity as the pianist in Jimmy’s Dixieland combo, but her own muse led her to modern styles. By hiring Morello for her trio, she drew on his innate musicianship to grow as a pianist. She loved both men dearly, and it took several sessions with a psychoanalyst for her to decide which man was best for her. De Barros also details McPartland’s turbulent (but non-sexual) relationship with composer Alec Wilder, and traces how Wilder’s influence paved the way for “Piano Jazz”.

Throughout the book, de Barros includes succinct descriptions and critiques of McPartland’s major recordings. He traces her development from a classically-oriented traditional player through her long 1950s residency at New York’s Hickory House (which codified her bebop style) and her gradual adoption of post-bop styles from the 1960s through the present. He accurately notes several of McPartland’s greatest efforts, including the Savoy and Capitol albums recorded at the Hickory House, her tribute albums to Wilder, Benny Carter, Mary Lou Williams and Billy Strayhorn, and her piano duet recordings, “Just Friends” and “85 Candles”. He also discusses the highs and lows of the “Piano Jazz” broadcasts, which were once available on Concord Jazz’s subsidiary Jazz Alliance, but are now available for streaming from NPR.

One of the book’s few weaknesses lies in de Barros’ flexible approach to chronology. He opens the book with a letter written by McPartland shortly after D-Day, then jumps back nearly a hundred years to relate the histories of her grandparents. While this sort of device has been used in many biographies, de Barros uses it to excess, leapfrogging forward and backward to cover different aspects of McPartland’s career. The overall effect is a muddled chronology that is unnecessarily confusing. Also confusing is de Barros’ approach to women musicians: at times, he shares McPartland’s indignation at being discussed differently than male counterparts, but then he offers elaborate descriptions of McPartland’s outfits from her album covers! There are also a few outright mistakes: the 1981 “Women in Jazz” series was made for A&E, not PBS, and comparing Teddi King to Mabel Mercer shows little understanding of either artist.

Despite these flaws, de Barros’ book ranks as one of the finest jazz biographies of recent years. McPartland had unsuccessfully attempted to write an autobiography for several years, but clearly it took an outsider to find her true core. While not everything in de Barros’ book is flattering, it accomplishes what few biographies do: it enhances the subject’s image instead of tarnishing it.