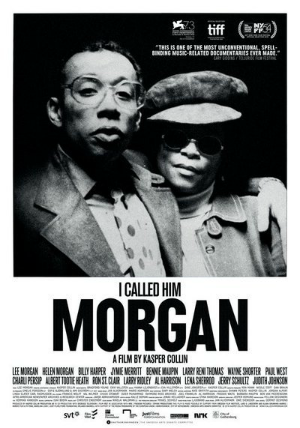

In the early morning hours of February 19, 1972, Lee Morgan and his sextet were about to close a week-long engagement at the notorious Manhattan night club, Slug’s. Morgan’s estranged common-law wife, Helen, who continued to act as his manager, entered the club for the first time that week. After an argument that ended with Helen being pushed into a snow bank, she re-entered the club and shot the trumpeter at point blank range. Lee Morgan died at the scene because the ambulance was delayed by an ongoing blizzard. For many years, there were few places where interested parties could learn further details about this tragic event. But in 2011, jazz historian and disc jockey Larry Reni Thomas published an article which summarized an interview he held with Helen, one month before her death. In that interview, a (possibly intoxicated) Helen presented a highly subjective and rationalized version of her life story, before and during her relationship with Lee. The audio recording of that interview plays a key role in Kasper Collin’s remarkable documentary, “I Called Him Morgan”.

In the early morning hours of February 19, 1972, Lee Morgan and his sextet were about to close a week-long engagement at the notorious Manhattan night club, Slug’s. Morgan’s estranged common-law wife, Helen, who continued to act as his manager, entered the club for the first time that week. After an argument that ended with Helen being pushed into a snow bank, she re-entered the club and shot the trumpeter at point blank range. Lee Morgan died at the scene because the ambulance was delayed by an ongoing blizzard. For many years, there were few places where interested parties could learn further details about this tragic event. But in 2011, jazz historian and disc jockey Larry Reni Thomas published an article which summarized an interview he held with Helen, one month before her death. In that interview, a (possibly intoxicated) Helen presented a highly subjective and rationalized version of her life story, before and during her relationship with Lee. The audio recording of that interview plays a key role in Kasper Collin’s remarkable documentary, “I Called Him Morgan”.

Collin opens the film with a summary of its final act. Cinematographer Bradford Young sets the scene with an abstract upward view of falling snow. The odd shapes of the snowflakes are reminiscent of dust and ash, and the eerie incidental music (uncredited, but probably the work of Gary Welch and Bree Winwood) foreshadows the haunting story. Then Thomas tells us about his first meeting with Helen Morgan, and the long delay before she agreed to an interview. Once we start to hear portions of that interview, Collin alternates between the life stories of Helen and Lee. Eschewing jazz critics and a voiceover narrator, Collin relates Lee’s history through anecdotes told by colleagues like Wayne Shorter, Paul West, Jymie Merritt, Bennie Maupin, Larry Ridley and Albert “Tootie” Heath. More importantly, Collin lets us hear Lee’s music. While there are points where sound bites are laid over the music, there are still plenty of opportunities for the audience to hear and appreciate Lee Morgan’s artistry without commentary. Further, Collin has picked music from either end of Morgan’s career, so viewers can grasp the changes that occurred in his music between 1956 and 1972.

In the interview, Helen paints herself as a tough New Yorker. Born in the South, she pulled herself out of a difficult childhood—she bore two children by the time she was 14, married a bootlegger at 17, and soon became a widow—and through sheer fortitude, restarted her adult life in New York City. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, her Hell’s Kitchen apartment became an open house for musicians. She offered a haven from the hardscrabble urban life with homemade food and great music. At some point, Lee Morgan found his way to her door. He had been a heroin addict for several years, and had sold his horn and pieces of his clothing to maintain his habit. Helen retrieved his overcoat and his trumpet from the pawnbroker, and took Lee under her wing. Lee checked into a Bronx hospital on the methadone program, and after his release, Helen helped him start a new band and land new gigs. Things started to turn sour for the Morgans in 1971, when Lee reconnected with an old friend, Judith Johnson.

It is at this point in the narrative where Collin’s film starts to fall apart. Thomas’ original article includes a stunning accusation from Helen which does not appear in the film: she claims that Lee and Judith were taking cocaine together. In the film, Judith states that Lee’s sexual drive was “very, very, very, very, very, very, very diminished” (funny, every “very” makes me question her credibility even more), but if that was the case, Helen would have been aware of that too. So, in the film, when Helen says that she caught Lee and Judith in the bathroom “doing…you know”, she didn’t catch them having sex; they were shooting up! This hidden fact might be Helen’s best justification for her heinous actions, as Judith was apparently undoing all the drug rehabilitation that Helen had accomplished. Of course, there is every reason to doubt Helen’s word, as her interview basically amounts to a deathbed confession. In his attempt to restore Helen’s reputation, Collin conveniently omits a claim from one of Helen’s children—first reported in James Gavin’s award-winning history of Slug’s—that Helen had stabbed her first husband. If that is true, Helen was literally and figuratively, a black widow. (More hidden information from Helen’s life can be found in Adam Shatz’ superb article on Paris Review).

In watching this film, my biggest shock was the incredible miscarriage of justice that occurred in the wake of the murder. Despite a massive snowstorm, Slug’s was packed on the night of Morgan’s murder. Thus, there were many witnesses to the crime. However, the prosecution seemed unable (or unwilling?) to assemble a case, and in August 1973, they allowed Helen to plead guilty to second-degree manslaughter. The New York Penal Code presently lists the minimum sentence for that crime as 25 years in prison; somehow, Helen was released after less than two years in jail, and while still on probation, she was allowed to leave the state for a visit to her childhood home in North Carolina! She moved there permanently in the mid-1970s, where she became “a celebrity in her church”.

One online reviewer wrote that this film probably gave the most complete story of Lee Morgan’s murder that we would ever hear. That is a shame, for while Collin’s film completely deserves all of its accolades, the omission of crucial facts in Helen’s story (or at least, the acknowledgement that discrepancies exist) leave this fascinating tale incomplete. In a way, telling this story is like proving a JFK conspiracy theory: most of the principals are dead, and no one is likely to be prosecuted. However, we do have an obligation to history, and these stories—no matter how displeasing—need to be told accurately. As our current government displays on a daily basis, we cannot improve our fate if we do not learn from our past.