If you (or someone you know) is new to jazz and trying to understand just how this music works, buy a copy of Gary Burton’s new autobiography, “Learning to Listen” (Berklee Press) and proceed directly to Chapter 28. That chapter, “Understanding the Creative Process” contains the most eloquent descriptions of improvisation and jazz performance practices that I’ve ever read. In answering the old question “What does a jazz musician think about when they improvise?” Burton tells us that he tries to not think of anything in particular, so as not to disturb his unconscious mind, which is actually creating the music. He elaborates that he (and all jazz musicians for that matter) can communicate with the unconscious mind to guide the performance from being repetitious or complex. He makes precise analogies to human speech and to the perceptional abilities of humans and animals. It is an intelligent essay that draws on Burton’s dual careers as educator and musician.

If you (or someone you know) is new to jazz and trying to understand just how this music works, buy a copy of Gary Burton’s new autobiography, “Learning to Listen” (Berklee Press) and proceed directly to Chapter 28. That chapter, “Understanding the Creative Process” contains the most eloquent descriptions of improvisation and jazz performance practices that I’ve ever read. In answering the old question “What does a jazz musician think about when they improvise?” Burton tells us that he tries to not think of anything in particular, so as not to disturb his unconscious mind, which is actually creating the music. He elaborates that he (and all jazz musicians for that matter) can communicate with the unconscious mind to guide the performance from being repetitious or complex. He makes precise analogies to human speech and to the perceptional abilities of humans and animals. It is an intelligent essay that draws on Burton’s dual careers as educator and musician.

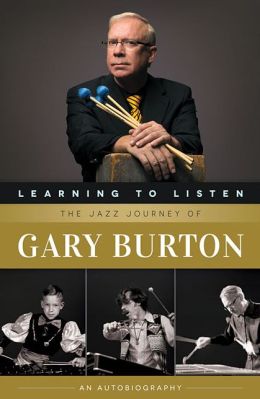

Born in Indiana in 1943, Burton was a child prodigy who began playing when he was six years old. He won a television amateur talent show at 10, and started performing professionally while still in high school. After graduation, he spent a summer working with country musicians such as Hank Garland and Boots Randolph (thus laying the groundwork for his later country/jazz LP “Tennessee Firebird”). While still underage, he had launched his recording career with RCA, recording primarily under his own name. He then moved to Boston where he became a student at the Berklee School of Music (and, in a move rarely replicated with other artists, his record company helped pay his tuition and living expenses!) By the time he was old enough to vote, he was touring with George Shearing and soon after that, he became the vibraphonist and road manager for the Stan Getz Quartet. Such a quick ascent to jazz stardom must have quite overwhelming for Burton, and it certainly informs Burton’s sharp criticisms of Shearing’s restrained musical style and Getz’s notorious mood swings.

After leaving Getz in 1967, Burton created his own quartet (with Larry Coryell, Steve Swallow and Roy Haynes) which fused rock music and jazz on the album “Duster“. Moving into the 1970s, he recorded duets with Chick Corea, performed solo vibraphone concerts, and assembled new groups that brought musicians like Pat Metheny, Makoto Ozone and Julian Lage into the spotlight. Burton talks about each of his albums, but does not go into details about the individual tracks, leaving the analysis for others. Along the way, he discusses several of his heroes and inspirations in a series of short profiles. His piece on Thelonious Monk tells of the pianist’s eccentricities while reflecting Burton’s respect for his artistry. He first speaks of a shared double bill at the Village Vanguard where Monk continuously played the melody of his tunes throughout his quartet’s set (and was finally lifted from the piano bench by drummer Ben Riley). But then, Burton describes a later meeting with Monk from the 1971 Giants of Jazz tour where Monk didn’t even recognize the vibist. Burton is also quite sympathetic to the drug-induced plights of Bill Evans, but cannot muster the same sympathy for Anita O’Day. He’s mean and spiteful when telling how the Art Ensemble of Chicago’s large collection of instruments once delayed his own plane departure from Italy. Elsewhere in the book, Burton goes into considerable detail about his educational career at Berklee. He has been both an instructor and an administrator at his alma mater, and he was responsible for adding rock music, music therapy and music technology to the curriculum.

In the most personal parts of the book, Burton discusses his struggles with being a homosexual. When he first realized that he was gay, he could not come out because of the rampant anti-gay sentiments of most jazz musicians. He notes that when his career started in the 1960s, homosexuality was considered a sickness. There’s a certain sting every time Burton recounts being called a “faggot” (especially when the epithet came from his boss, Getz). Eventually, Burton went through psychoanalysis and two straight marriages before coming out privately in the early 1990s, and publically on Terry Gross’ radio show “Fresh Air”. Burton is candid but not graphic as he tells of his gay life, and at the end of the book, he says that he would be happy to be remembered as “the gay man who happened to be a jazz musician”, “the jazz musician who happened to be gay” or just “the jazz musician who played with four mallets”. Burton’s book doesn’t provide all of the answers to his life or career (like why and how he plays with four mallets), but it is a fascinating narrative by an important and sophisticated musician.