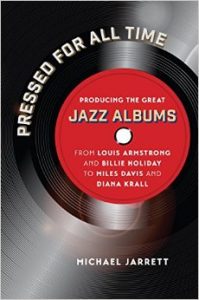

One of the best side effects of the current vinyl revival is that it emphasizes record albums as artistic entities. The first albums, released in the mid-30s, were binders of 78 rpm singles, brandished with cover art and liner notes. When LPs replaced 78s, musicians used the album format to make unique statements, linking all of the tracks through common personnel or thematic concepts. As the art of the album developed, producers took a greater role in shaping the final product. Depending on the artist’s vision, the jazz producer’s job could be as menial as bringing in enough beer and sandwiches to last through the recording session, or as complex as editing and re-structuring tapes. While jazz producers aren’t exactly unsung heroes—many of the best producers have been praised or damned in print—Michael Jarrett’s book “Pressed for All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums” (University of North Carolina Press) offers an interesting oral history of jazz producers from 1936 to the present.

One of the best side effects of the current vinyl revival is that it emphasizes record albums as artistic entities. The first albums, released in the mid-30s, were binders of 78 rpm singles, brandished with cover art and liner notes. When LPs replaced 78s, musicians used the album format to make unique statements, linking all of the tracks through common personnel or thematic concepts. As the art of the album developed, producers took a greater role in shaping the final product. Depending on the artist’s vision, the jazz producer’s job could be as menial as bringing in enough beer and sandwiches to last through the recording session, or as complex as editing and re-structuring tapes. While jazz producers aren’t exactly unsung heroes—many of the best producers have been praised or damned in print—Michael Jarrett’s book “Pressed for All Time: Producing the Great Jazz Albums” (University of North Carolina Press) offers an interesting oral history of jazz producers from 1936 to the present.

The material stems from interviews conducted by Jarrett over the last quarter-century, and he resists the temptation to compare the varied techniques of different producers. Most of Jarrett’s opinions appear in the introductions to the main chapters, and between the lines of the interviews. He lets George Avakian and Chris Albertson tell negative stories about John Hammond, and along the way, there are insinuations that he wasn’t much of a producer. Of course, this is total nonsense: Hammond’s role in both artist support and hands-on record producing has been well-documented—everyone in the book seems to have forgotten his LPs for Vanguard and Columbia—and while Hammond clearly abused his power on numerous occasions, there is no doubt of his importance in the field of jazz recording. Norman Granz fares a little better. There are certainly less negative comments about him, but no one really takes up his banner either. While Granz could be brusque and stubborn, he knew how to create superb jazz recordings in quantity, and his efforts greatly improved the fortunes of musicians like Roy Eldridge, Zoot Sims and Ella Fitzgerald. Even if Granz would not agree to an interview with Jarrett, why not talk to Granz’ biographer, Tad Hershorn? And why is there not a detailed discussion about Alfred Lion and Frank Wolff, who created Blue Note’s amazingly consistent string of high-quality recordings?

Jarrett’s book hits its stride when it celebrates the works of great producers like George Avakian, Milt Gabler, Ahmet Ertegun, Lester Koenig, Orrin Keepnews, Teo Macero, Nat Hentoff, Bob Thiele, Joel Dorn, Michael Cuscuna, Creed Taylor and John Snyder. We get a clear picture of how each of these men worked in the studio, how they dealt with artists, handled interference from outsiders, and created unique albums. Avakian and Macero speak about editing recordings of Miles Davis, Koenig’s son tells of his father’s involvement in the Hollywood studios and how the blacklist caused his career shift into the record business. We discover the different approaches to recording by engineers Tom Dowd (Atlantic) and Rudy Van Gelder (Prestige, Blue Note). Hentoff, Thiele and Dowd talk of their relationships to Charles Mingus, John Coltrane and Rahsaan Roland Kirk, respectively, while Taylor and Snyder discuss their efforts to balance commerce and art at CTI. The book is copiously illustrated with cover photos of classic jazz albums, but readers should not expect detailed explanations of what made each record a masterpiece. In fact, there are several examples where there is no direct discussion of the featured album! Jarrett’s focus is clearly on the producer’s overall work rather than individual successes. The record covers seem to be an attempt to market the book, rather than a guiding principal for the narrative.

“Pressed for All Time” is an enjoyable read, and it contains many factual tidbits not to be found anywhere else. While I question the motive of including the record covers, I am intrigued by some of the obscure recordings, including albums by Kip Hanrahan, Marilyn Crispell and the Italian Instabile Orchestra. Just how long the album format continues to exist is a matter of conjecture, but it seems likely that production will continue to play an important role in the creation of new recordings—even if that work is handled by the artists instead of record company employees or independent contractors. As Jarrett’s narrative makes clear, there’s more to being a producer than just ordering in food and drinks.