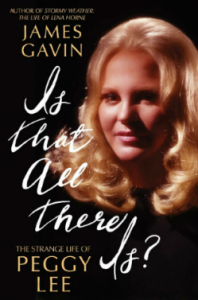

One of the earliest lessons Peggy Lee ever learned about singing was the power of understatement. As a teenager listening to Bing Crosby, she heard how the microphone could amplify a singer’s volume without sacrificing a sense of intimacy. From Count Basie, she discovered how omitting a note could be more powerful than adding thirty. It could be said that this single concept defined everything Lee sang in her professional career. While she had the ability to sing fortissimo over an orchestra, she saved those effects for special arrangements like her whirling Latin version of “Lover”. On most of her repertoire, she would sing softly so that her listeners would focus on the tiniest musical details. As captivating as her records are, she is fascinating to watch on film. Even as a 22-year old singing “Why Don’t You Do Right” with the Benny Goodman band, she mesmerizes us with every raised eyebrow and come-hither look, making us wonder what was happening behind that perfectly-sculpted face and that sensuous voice. In his new biography, “Is That All There Is: The Strange Life of Peggy Lee” (Atria), James Gavin offers an in-depth exploration of Lee’s life and music.

One of the earliest lessons Peggy Lee ever learned about singing was the power of understatement. As a teenager listening to Bing Crosby, she heard how the microphone could amplify a singer’s volume without sacrificing a sense of intimacy. From Count Basie, she discovered how omitting a note could be more powerful than adding thirty. It could be said that this single concept defined everything Lee sang in her professional career. While she had the ability to sing fortissimo over an orchestra, she saved those effects for special arrangements like her whirling Latin version of “Lover”. On most of her repertoire, she would sing softly so that her listeners would focus on the tiniest musical details. As captivating as her records are, she is fascinating to watch on film. Even as a 22-year old singing “Why Don’t You Do Right” with the Benny Goodman band, she mesmerizes us with every raised eyebrow and come-hither look, making us wonder what was happening behind that perfectly-sculpted face and that sensuous voice. In his new biography, “Is That All There Is: The Strange Life of Peggy Lee” (Atria), James Gavin offers an in-depth exploration of Lee’s life and music.

It’s not always a pleasant journey. Lee was born as Norma Deloris Egstrom in North Dakota, where the monochromatic geography of the plains mirrored the staunch, reserved, God-fearing attitudes of the residents. Her father was an alcoholic, and her loving mother passed away when Norma was four. Her stepmother was a tough, brutal woman who certainly abused Norma verbally and possibly physically. Norma escaped as soon as she could. She started her professional career as a radio singer (where a program director gave Norma her professional name) and she eventually moved to Chicago, where she was hired by Goodman. After World War II, when singers took the spotlights from the big bands, she started a solo singing career partnered with the Goodman band’s guitarist, Dave Barbour. Barbour and Lee made a great pair, both as an artistic partnership and as a newlywed couple. They composed and performed a string of early hits, including “It’s a Good Day”, “Mañana” and “What More Can a Woman Do”, but Barbour’s alcoholism led to the couple’s divorce and the end of their professional collaborations. Lee also became addicted to alcohol and prescription drugs, and while her star rose, her personal life descended into chaos. Lee was a hypochondriac, a pathological liar and a diva (a dangerous combination) and she quickly gained a reputation for being difficult and highly eccentric. Lee made up her official biography seemingly out of whole cloth. Gavin does his best to unravel the knots that Lee tied up so well.

Gavin paints a portrait of Lee as a woman constantly at war with everyone in her world—musicians, club owners, personal assistants—yet who can’t grasp why she was unable to find a suitable lover or husband. Lee went through three short-lived marriages in her years after Barbour, and later in life, she invented the fable that she and Barbour were on the verge of reconciliation at the time of his death in 1965. Professionally, Lee seemed trapped in an unchanging pattern, where new and promising projects disintegrated because of her outrageous demands, and in the process, she burned bridges with long-time friends and associates. Unfortunately, Gavin chooses to document every one of these similar incidents in great detail. How many times must we read about Lee’s excessive substance abuse, her voracious sexual appetite, the lawsuits (some frivolous, some not), the verbal abuse to associates, and the shocking neglect of her daughter? I understand that these stories need to be told before the witnesses pass away (especially since Lee’s daughter Nicki died just hours before I wrote this review). Still, these background stories—some of which are undoubtedly tainted by personal experiences—are not the reason why Peggy Lee is legendary, and I doubt that many readers will be interested in examining her recordings after hearing these tales of turmoil.

To be fair, Gavin does include discussions of Lee’s greatest recordings, and he does an exceptional job of explaining the music to a layman audience. We learn how Lee used her longstanding admiration for black music to create distinctive renditions of songs like “Fever” and “I’m A Woman”. Gavin documents Lee’s appearances at New York’s Basin Street East, which was the site of one of her finest albums (although Gavin never mentions that the actual live recordings from the club were only issued after Lee’s death). Yet there could have been much more. Lee’s most influential recordings were made between 1942 (“Why Don’t You Do Right”) and 1969 (“Is That All There Is”). A vivid discussion of the recording session for the latter song appears almost exactly in the middle of the book, leaving over 250 pages of Lee’s behind-the-scenes melodramas and a handful of lesser recordings. Gavin should have condensed the latter half of the book; he could have still hit the high and low points of Lee’s post-1970 career and spared us all of the gruesome details. Clearly, Peggy Lee caused many of her own problems, but if her legacy is to be preserved, the focus of her biography needs to be on her music and not her personal life.