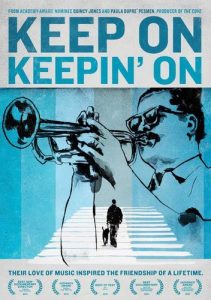

F. Scott Fitzgerald got it wrong: not only are there second acts in American lives, some of them are quite extraordinary. In jazz, one of the best examples is Clark Terry. Terry would have made it into the jazz history books as one of the few musicians to play with both Count Basie and Duke Ellington, his pioneering role as the first African-American studio musician at NBC, and for his unique sound on trumpet and flugelhorn (which, as one commentator put it, has no trace of metal). Yet he has made an even greater impact in his second act, as a mentor and teacher to thousands of jazz students. His first students included Quincy Jones and Miles Davis (both while they were still in school), but it would be hard to find any jazz musician who has not been touched by Clark Terry. A new documentary, “Keep On Keepin’ On”, features Terry as both musician and educator as he helps the young pianist Justin Kauflin discover his own voice.

Early in the film, Terry tells Kauflin that “challenges are a part of life” and both men have plenty of challenges to overcome. Terry is in his 90s, and the diabetes he has had since the 1950s is taking its toll on his health. The blood circulation to his legs is dangerously low, and he’s losing his sight. Kauflin, 26, started playing the piano after losing his sight in the sixth grade. A quick learner, Kauflin developed both the ability and the determination to succeed as a jazz musician. What he needs is a big break to separate him from the competition. At the beginning of the film, that big break is still elusive. He lives in New York City, but he has trouble finding enough gigs to pay the rent. His blindness prevents him from getting a day job, so he moves back to his parents’ home in Virginia Beach, Virginia. But one remaining connection makes an important difference. In the late 90s, Kauflin had been one of Terry’s students at William Paterson University. The two men had maintained a student/teacher relationship since then, even after Kauflin had moved back home and Terry had relocated to his wife’s hometown of Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Terry’s declining health limited his travel to between home and the hospital, so Kauflin traveled to Pine Bluff on a regular basis. Most of the time, they met at Terry’s home for extended lessons, but as Terry’s condition worsened, Kauflin visited Terry in the hospital, sometimes playing a portable keyboard, and other times just offering Terry friendly conversation or a hand to hold.

Early in the film, Terry tells Kauflin that “challenges are a part of life” and both men have plenty of challenges to overcome. Terry is in his 90s, and the diabetes he has had since the 1950s is taking its toll on his health. The blood circulation to his legs is dangerously low, and he’s losing his sight. Kauflin, 26, started playing the piano after losing his sight in the sixth grade. A quick learner, Kauflin developed both the ability and the determination to succeed as a jazz musician. What he needs is a big break to separate him from the competition. At the beginning of the film, that big break is still elusive. He lives in New York City, but he has trouble finding enough gigs to pay the rent. His blindness prevents him from getting a day job, so he moves back to his parents’ home in Virginia Beach, Virginia. But one remaining connection makes an important difference. In the late 90s, Kauflin had been one of Terry’s students at William Paterson University. The two men had maintained a student/teacher relationship since then, even after Kauflin had moved back home and Terry had relocated to his wife’s hometown of Pine Bluff, Arkansas. Terry’s declining health limited his travel to between home and the hospital, so Kauflin traveled to Pine Bluff on a regular basis. Most of the time, they met at Terry’s home for extended lessons, but as Terry’s condition worsened, Kauflin visited Terry in the hospital, sometimes playing a portable keyboard, and other times just offering Terry friendly conversation or a hand to hold.

Director Alan Hicks was a classmate of Kauflin’s at Paterson, and the two students played together in Terry’s school combo. “Keep On” is his first film, and he displays exceptional skill as a storyteller. Part of the joy of this film is watching the story unfold, so I will restrain from revealing the plot, even at the expense of expressing precisely why I admire this film. However, I advise you to pay special attention to the sequence on Kauflin’s performance in the semi-finals of the Thelonious Monk Institute’s piano competition. Hicks builds up the tension as Terry offers his long-distance support (and a personal memento), and Kauflin tries to manage his stage fright as he prepares for the biggest concert of his life. The final two scenes of this sequence—and you’ll recognize them when you see them—are simply unforgettable because Hicks seems to be following an established convention, but is actually leading us down a different path. It is stunning filmmaking, and in retrospect, most appropriate for a documentary about jazz.

Near the end of the film, Terry has to go to the hospital for major surgery. He  confesses to his wife Gwen that he is scared that he won’t survive the operation. Yet he’s less concerned about his own life as he is about his students: There’s a whole lot of people I’d love to help, but I can’t stay here long enough to do it. Thankfully, Terry does survive and he provides Kauflin his golden opportunity by simply letting him play for some of his illustrious friends, including Jones and vocalist Dianne Reeves. Needless to say, Kauflin rises to the occasion (Judging by information in the film’s epilogue, we may be hearing a lot more of Kauflin in the months to come).

confesses to his wife Gwen that he is scared that he won’t survive the operation. Yet he’s less concerned about his own life as he is about his students: There’s a whole lot of people I’d love to help, but I can’t stay here long enough to do it. Thankfully, Terry does survive and he provides Kauflin his golden opportunity by simply letting him play for some of his illustrious friends, including Jones and vocalist Dianne Reeves. Needless to say, Kauflin rises to the occasion (Judging by information in the film’s epilogue, we may be hearing a lot more of Kauflin in the months to come).

In the period since this article was written, it has since appeared on DVD. It is a film that must be seen by all jazz fans, and it could easily bring the music to a greater audience. But I hope that it also inspires jazz musicians to offer guidance to younger players. In the past few years, we’ve lost several of jazz’s best mentors, including Betty Carter, Billy Taylor, and since the release of this film, Clark Terry.

As Jones so eloquently states in “Keep On Keepin’ On”, The most important thing you can give to a young musician is someone who believes in them. It makes you believe in yourself. Well put, Q; well put.