No complaints and no regrets.

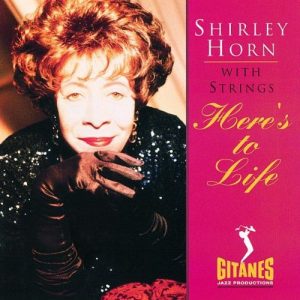

A few days ago, I saw those five words as a Facebook post from a well-known  jazz vocalist. It needed no citation. Several readers recognized the quote as the opening lyrics of “Here’s To Life”, the title song from Shirley Horn’s greatest album. Later that day, I was engaged by another well-known singer for a research project involving female singers of the past. Once again, Shirley Horn was the center of conversation. As I immersed myself in documentaries, concert performances and interviews with Horn, it struck me that all of the material centered on that same album. “Here’s To Life” was Horn’s first collaboration with Johnny Mandel. It’s been hailed as a masterpiece since its release in 1992. It never fails to touch me as a listener, and the album’s themes are even more profound to me now at age 50 than they were when I first heard the album at age 32.

jazz vocalist. It needed no citation. Several readers recognized the quote as the opening lyrics of “Here’s To Life”, the title song from Shirley Horn’s greatest album. Later that day, I was engaged by another well-known singer for a research project involving female singers of the past. Once again, Shirley Horn was the center of conversation. As I immersed myself in documentaries, concert performances and interviews with Horn, it struck me that all of the material centered on that same album. “Here’s To Life” was Horn’s first collaboration with Johnny Mandel. It’s been hailed as a masterpiece since its release in 1992. It never fails to touch me as a listener, and the album’s themes are even more profound to me now at age 50 than they were when I first heard the album at age 32.

“Here’s To Life” was never promoted as a concept album, but there is a constant theme that unites the songs into a unified whole. It is not just an album about life and all its resultant ups and downs, but an album about survival. Horn was in her late 50s when she recorded this CD, and the wisdom and experience of maturity comes through in every syllable she sings. Horn never tells us that life is easy; indeed, she acknowledges the difficulties, but insists that life must continue and we must be resilient despite our troubles. Horn, who was well-known for her love of great lyrics, selected all of the songs for the album, so it was no accident that the songs fused together into a coherent theme. Even with the presence of three Mandel songs on the track list, the real catalyst for tying this music together was the title track. Written by Artie Butler and Phyllis Molinary specifically for Horn, “Here’s To Life” has a poetic lyric than encapsulates the themes developed later in the album. It has the same autumnal quality as the rest of the album’s lyrics, the implied memories of romances good and bad, and the desire to accept life as it is, while discovering new joys and adventures.

The three Mandel songs (each written with different lyricists) contribute their own angles to the album’s theme. “A Time For Love”, probably the best-known of the three, features the pastoral lyrics of Paul Francis Webster, and celebrates love itself and all of the idyllic memories of young romance. Morgan Ames’ lyric to “Quietly There” is about a love affair on the brink of collapse, and “Where Do You Start”, perhaps the finest lyric creation by Marilyn & Alan Bergman, speaks of the absolute end of an affair, with the incidental properties of a couple being split up as they prepare to go their separate ways. Horn’s measured and thoughtful performances of these songs make us think about the lyrics and what they mean. There’s a little chuckle she inserts after the words a time for holding hands together that implies an entire back story of a long-past romantic memory. On “Quietly There” Horn brings out the subtle changes of context that Ames used in setting the title line, and the matter-of-fact way that she sings “Where Do You Start” masks the deep emotional heartbreak that marks the lyric’s subtext. On “A Time For Love” and “Quietly There”, Wynton Marsalis offers superb, understated solos that perfectly compliment Horn’s vocals. The parts were originally slated for Miles Davis, but the trumpeter died before the recording sessions occurred. One can only imagine how different these tracks would have sounded with Davis in a featured role.

One of the most telling examples of how Horn could transform her material is the album’s penultimate track, “If You Love Me”. The credits and notes fail to acknowledge that the song is an English adaptation of “Hymne á l’Amour”, a song co-composed and performed by Edith Piaf. The song was written to Piaf’s great love, boxer Marcel Cerdan. Piaf premiered the song in a live performance about 6 weeks before Cerdan was killed in a plane crash. She recorded it about 6 months after the tragedy with an overblown arrangement featuring full orchestra and chorus. There is a world of difference between the throbbing, emotional Piaf recording and Horn’s understated, conversational version. Horn’s arrangement starts on the bridge, and she simply asks Shall I catch a shooting star? Shall I bring it where you are? If you want me to, I will as if it was the smallest task imaginable. There is an inevitable buildup to the climax, and while it could be thunderous in Horn’s live trio versions, on the recording, the strings and horns build it up to just the right level and then back off to let Horn take the last lines on her own.

On all but two of the songs, Horn recorded her own trio versions first and then sent the tapes to Mandel for him to arrange orchestral backdrops. Mandel, always the most sensitive of arrangers, made his contributions seamless with the trio. In fact, it’s quite surprising to realize that this album was made on two coasts over the period of several months. While Horn was rather slow in adding the songs to her live repertoire (in a Carnegie Hall concert I attended about a month after the album’s release, Horn’s only performance from the new CD was “Return To Paradise”), most of them became highlights of her later concerts. I remember a thrilling trio version of “Here’s To Life” from a concert at the Kennedy Center (ironically, the title tune was one of the songs from the album where Horn didn’t play piano) and several stunning versions of “How Am I To Know” where the indefinite style of the trio arrangement led to long, exploratory tag endings by the group.

During a 2002 radio interview, Horn heard (apparently for the first time) a remixed version of “Return To Paradise” from the compilation album “Verve Remixed”. The DJ, Mark DeClive-Lowe, isolated Horn’s vocal and set it against an up-tempo electronica beat. Horn complained that he had broken up the melody and gave the remix a resounding thumbs-down. To my ears, the worst parts of the remix are the de-humanized sound of Horn’s voice, and the speeding up of the tempo. Horn was such a personal, conversational singer that the re-equalization of her voice removes all of her essence as a performer. But more disturbing is the tempo. Was DeClive-Lowe saying that young audiences were too frenetic and too impatient to listen to a thoughtful, measured performer like Shirley Horn? If so, they need to learn what Horn can still teach, even from the netherworld. For the art of Shirley Horn was in her infinite patience, and her unique way of making every word count. She was, and is, a master storyteller.