At the beginning of 1956, Duke Ellington was coming off a fallow period. Five years earlier, his star soloist alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges left the band to lead his own group. Several other key players left around the same time, and while Ellington was able to fill most of the void with young players like Clark Terry, Willie Cook and Louis Bellson, he found it difficult to replace Hodges, even with great players like Willie Smith and Hilton Jefferson in his employ. Ellington suffered an ever greater loss when composer-arranger Billy Strayhorn left in 1953 due to disagreements regarding royalties and composition credits. With Strayhorn gone, Ellington had to take on all of the writing for the band, and while he had done that work before, he was certainly accustomed to sharing the workload with Strayhorn.

By the end of 1955, Hodges and Strayhorn had returned to the fold. Hodges wrangled a comfortable salary from Ellington (there are many tales of Hodges on the bandstand rubbing his thumb and forefingers together, signaling Ellington that he wanted a raise). Strayhorn negotiated an agreement which insured that all future Ellington/Strayhorn collaborations were credited under both names, and that Strayhorn would be recognized for his own compositions. In the end, Strayhorn didn’t get all of the credit he deserved (Ellington did his best, but Strayhorn’s name was conspicuously absent from liner notes and record reviews). Further, Ellington and Strayhorn perpetuated a myth that their composing styles were so similar that one of them could take up writing where the other left off, and no one could tell the difference. It was a myth that stood for many years until the manuscript scores of both men were collected and studied.

Strayhorn’s first project upon his return was an LP collaboration with vocalist Rosemary Clooney, “Blue Rose”. The album marked the Ellington band’s first recordings for Columbia since December 1952. It was an unusual project in that Clooney was pregnant and under doctor’s orders not to travel. So, in January 1956, the Ellington band recorded Strayhorn’s instrumental backgrounds in New York. Then Strayhorn traveled to Los Angeles where he rehearsed with Clooney, who then overdubbed her vocals in February. Such technical wizardry was uncommon in those days, but Columbia had used overdubbing before and their engineers were very good at making the final results transparent. Perhaps this session was the enticement Ellington needed to return to the Columbia roster, for while Strayhorn and Clooney were overdubbing in LA, Ellington routed his troops into a Chicago studio, where in just two days they recorded enough music to fulfill Ellington’s existing contract with Bethlehem Records.

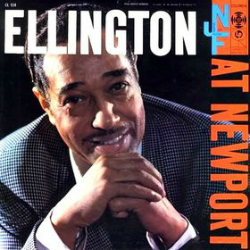

The Ellington orchestra was slated to perform at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1956. Ellington was planning to play a standard set (including his infamous “hits medley”), but both festival producer George Wein and Columbia Records’ A&R man George Avakian—who wanted to record the band live at Newport— convinced him that he needed to write something new to premiere at the festival. Ellington and Strayhorn complied with the “Newport Jazz Festival Suite”, but ironically it was tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves’ 27-chorus solo on the Ellington classic, “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” that caused a sensation with the festival audience. Within a few weeks, Ellington was on the cover of Time magazine, and the corresponding article told of the triumph at Newport.

The Ellington orchestra was slated to perform at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1956. Ellington was planning to play a standard set (including his infamous “hits medley”), but both festival producer George Wein and Columbia Records’ A&R man George Avakian—who wanted to record the band live at Newport— convinced him that he needed to write something new to premiere at the festival. Ellington and Strayhorn complied with the “Newport Jazz Festival Suite”, but ironically it was tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves’ 27-chorus solo on the Ellington classic, “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” that caused a sensation with the festival audience. Within a few weeks, Ellington was on the cover of Time magazine, and the corresponding article told of the triumph at Newport.

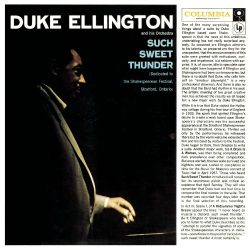

Less than two weeks after Newport, Ellington, Strayhorn and the orchestra traveled to Canada for the Stratford Shakespearean Festival. The band was scheduled to play on two non-consecutive nights, but Ellington and Strayhorn stayed for most of the week, catching performances of Shakespeare’s plays, and discussing the Bard with several of the festival’s staff members. Ellington promised a new suite of Shakespeare-related pieces for the 1957 festival. Ellington and Strayhorn realized they would need some time to research and develop the suite. Both men had the texts of Shakespeare’s complete works in their home libraries. Strayhorn’s knowledge of the plays was so thorough that some of the band members nicknamed him “Shakespeare”. Ellington knew his Shakespeare, too, and according to Don George, Ellington’s copy of the Shakespeare works was filled with underlined passages marking the characters and lines that piqued his interest. Ellington and Strayhorn collected these volumes and took them on the road so they could research while touring with the band. They sought out Shakespeare experts wherever they could find them, and over the course of a few months, they had conceptualized a new suite which would be called “Such Sweet Thunder”. The premiere was scheduled for April 28, 1957 at New York’s Town Hall, and the piece was slated to be recorded by Columbia.

Ellington and Strayhorn had a lot on their plate during late 1956 and early 1957. Starting in September 1956 (and continuing through the end of the year), the band recorded Ellington and Strayhorn’s idiosyncratic history of jazz, “A Drum is a Woman”. In addition to the Columbia LP, the piece was scheduled as an hour-long television special airing live and in color on May 8, 1957. The production involved singers, dancers and the Ellington band, and Ellington was in constant demand during the weeks preceding the broadcast. Because of these time restraints, the Shakespeare suite was written in just under three weeks. During this time, Ellington asked Strayhorn to rename a couple of his earlier pieces to fit the Shakespeare theme. It was not as wild of an idea as it sounded: a piece recorded under the title “Lately” became a musical portrayal of Cleopatra on her barge called “Half the Fun”, and the Hodges ballad feature “Pretty Girl” was transformed into the “Romeo and Juliet” scene, “The Star-Crossed Lovers”. Even utilizing these time-saving measures, the last movement of the work had not been composed when the premiere took place. Ellington substituted a previously recorded Paul Gonsalves feature called “Cop-Out”. According to George Avakian, no one in the audience got the joke: “It was such a straight crowd that they didn’t even know they were being put on.” By the end of the week, the suite had been completed (with a new finale, “Circle of Fourths”) and recorded for Columbia.

Instrumental music is basically abstract, but when a composer decides to write a descriptive work, he depends on his audience’s acceptance of the work’s  description in the program notes. This concept is particularly important with “Such Sweet Thunder” for some of the movements were composed without any reference to Shakespeare, and others originally depicted different scenes and characters than those listed in the final program. For example, the opening movement shares its title with the album. The suite’s title came from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, but the movement’s original title was “Cleo”. And if that wasn’t confusing enough, Ellington typically introduced the movement by saying that it was inspired by Othello’s wooing of Desdemona! The piece could have described Cleopatra on her barge, but the Othello reading works better: To impress Desdemona’s father—and eventually Desdemona herself—Othello tells of his experiences as a soldier and slave. He tells of being in a jungle amidst cannibals and men whose heads were below their shoulders. This is a great fit for Ellington, as “jungle music” was one of his early specialties. Set to a 12-bar blues structure, the opening movement features the plunger-muted trumpets that were part of Ellington’s repertoire at the Cotton Club. The piece also has a swagger that could represent the Moor’s confident walk, and while the mood softens during Ray Nance’s cornet solo—perhaps depicting Othello retelling his story to Desdemona—Sam Woodyard maintains the crackling backbeat throughout the movement. According to Strayhorn biographer Walter van de Leur (who has studied Strayhorn’s manuscript scores) this is the only instance in the suite where Ellington and Strayhorn wrote parts of the same movement. Van de Leur’s Strayhorn biography offers a breakdown of the choruses, but the measure numbers did not line up with what I counted from the recording. In an e-mail, van de Leur confirmed my educated guess that Strayhorn composed the four-bar interlude between the fourth and fifth choruses.

description in the program notes. This concept is particularly important with “Such Sweet Thunder” for some of the movements were composed without any reference to Shakespeare, and others originally depicted different scenes and characters than those listed in the final program. For example, the opening movement shares its title with the album. The suite’s title came from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, but the movement’s original title was “Cleo”. And if that wasn’t confusing enough, Ellington typically introduced the movement by saying that it was inspired by Othello’s wooing of Desdemona! The piece could have described Cleopatra on her barge, but the Othello reading works better: To impress Desdemona’s father—and eventually Desdemona herself—Othello tells of his experiences as a soldier and slave. He tells of being in a jungle amidst cannibals and men whose heads were below their shoulders. This is a great fit for Ellington, as “jungle music” was one of his early specialties. Set to a 12-bar blues structure, the opening movement features the plunger-muted trumpets that were part of Ellington’s repertoire at the Cotton Club. The piece also has a swagger that could represent the Moor’s confident walk, and while the mood softens during Ray Nance’s cornet solo—perhaps depicting Othello retelling his story to Desdemona—Sam Woodyard maintains the crackling backbeat throughout the movement. According to Strayhorn biographer Walter van de Leur (who has studied Strayhorn’s manuscript scores) this is the only instance in the suite where Ellington and Strayhorn wrote parts of the same movement. Van de Leur’s Strayhorn biography offers a breakdown of the choruses, but the measure numbers did not line up with what I counted from the recording. In an e-mail, van de Leur confirmed my educated guess that Strayhorn composed the four-bar interlude between the fourth and fifth choruses.

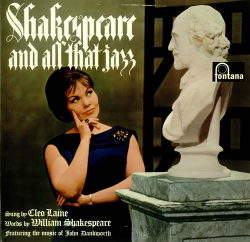

From a musicological standpoint, the most distinctive movements in “Such Sweet Thunder” are the four sonnets. Only two of the four pieces survive in autograph scores and both of those are in Ellington’s hand. It’s probably a safe bet that Ellington composed all four, as Strayhorn never claimed any of them as his own. In the sonnets, Ellington follows the exact structure that Shakespeare used: 14 lines of ten beats each in iambic pentameter, set in three quatrains and a closing couplet. As Jack Chambers has noted, Ellington also followed the rhythm of the poetic lines, putting all of the rhymes, tied notes and held notes on the second or fourth beats of the measure. With this strict attention to the poetic structure, the texts of any of Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets can be overlaid onto Ellington’s melodies without any alterations. For example,  when Cleo Laine recorded two of these pieces for her 1964 LP “Shakespeare and All That Jazz”, she used Sonnet 147 (“My Love is as a Fever”) for “Sonnet for Caesar” and Sonnet 40 (“Take All My Loves”) for “Sonnet to Hank Cinq”. The original setting of “Sonnet for Caesar” features Jimmy Hamilton’s clarinet against sustained chords from the trombone section, a questioning motive from the low saxophones and a martial background from Woodyard. “Hank Cinq” (aka Henry V) is a complete contrast with Britt Woodman playing a brisk wide-ranging melody—spanning two octaves and a fourth!—with his gruff trombone sound. In the original liner notes, Ellington stated that “the changes in tempo have to do with the changes of pace and the map as a result of wars”. The “Sonnet for Sister Kate” is another trombone feature, this time for plunger specialist Quentin Jackson. The crying effect Jackson gets from his horn certainly sounds like the wailing of Katarina as she is being deliberately mistreated by Petruccio in “Taming of the Shrew”. Ellington made the source of the other sonnet a mystery. As he explained it, the title “Sonnet in Search of a Moor” might refer to Othello (the Moor of Venice), the witches of “Macbeth” (who lived on a moor), or an abstract piece whose title is a pun on the French word for love, amour. Since Othello and the Witches have their own movements elsewhere in the suite, I think the pun might be the key to this melancholy episode. Ellington starts the movement with an extended piano introduction that spans the entire range of the keyboard (he later referred to it as his “hi-fi introduction”). Jimmy Woode plays the primarily stepwise melody on bass, backed by a clarinet trio.

when Cleo Laine recorded two of these pieces for her 1964 LP “Shakespeare and All That Jazz”, she used Sonnet 147 (“My Love is as a Fever”) for “Sonnet for Caesar” and Sonnet 40 (“Take All My Loves”) for “Sonnet to Hank Cinq”. The original setting of “Sonnet for Caesar” features Jimmy Hamilton’s clarinet against sustained chords from the trombone section, a questioning motive from the low saxophones and a martial background from Woodyard. “Hank Cinq” (aka Henry V) is a complete contrast with Britt Woodman playing a brisk wide-ranging melody—spanning two octaves and a fourth!—with his gruff trombone sound. In the original liner notes, Ellington stated that “the changes in tempo have to do with the changes of pace and the map as a result of wars”. The “Sonnet for Sister Kate” is another trombone feature, this time for plunger specialist Quentin Jackson. The crying effect Jackson gets from his horn certainly sounds like the wailing of Katarina as she is being deliberately mistreated by Petruccio in “Taming of the Shrew”. Ellington made the source of the other sonnet a mystery. As he explained it, the title “Sonnet in Search of a Moor” might refer to Othello (the Moor of Venice), the witches of “Macbeth” (who lived on a moor), or an abstract piece whose title is a pun on the French word for love, amour. Since Othello and the Witches have their own movements elsewhere in the suite, I think the pun might be the key to this melancholy episode. Ellington starts the movement with an extended piano introduction that spans the entire range of the keyboard (he later referred to it as his “hi-fi introduction”). Jimmy Woode plays the primarily stepwise melody on bass, backed by a clarinet trio.

Ellington takes a great deal of poetic license with two further movements. “Lady Mac” is not the scheming and eventually insane Queen of Scotland we encounter in “Macbeth”. Ellington portrays her with a ragtime-tinged jazz waltz, claiming in his concert introductions that she was indeed a woman of royal birth, but “we suspect she had a little ragtime in her soul”. Whether or not the listener buys into Ellington’s premise, the piece is a charming interlude featuring a fine melody statement by the saxophone section which blossoms into a variation by the brass section. Ellington’s piano adds commentary throughout, and Russell Procope and Clark Terry play graceful solos on alto sax and flugelhorn, respectively. The last chorus foresees Lady Macbeth’s downfall with strong, stabbing triplet block chords by the ensemble and a striking “doomsday” motive—a low, accented descent of a minor second—at the end (Versions of this motive also appear at the conclusion of “Such Sweet Thunder” and “Sonnet to Hank Cinq”; its exact textual purpose is unclear, but had it been used in more of the movements, it might have acted as a glue to hold this expansive suite together). On “The Telecasters”, Ellington combines characters from two plays: the three Witches from “Macbeth”—portrayed by the trombone trio—and Othello’s nemesis, Iago—played by baritone saxophonist Harry Carney. Ellington explained the title by noting that all four characters always had something to say. His setting starts with the trombones arguing with Woode’s bass, and then calmly backing Carney’s stopping-and-starting melody statement. Later, the piece becomes a true conversation between Carney and the trombones, with the principals commenting on each other’s musical ideas.

Billy Strayhorn composed three movements for “Such Sweet Thunder”. The  one that he wrote specifically for the suite is the delightful “Up and Down, Up and Down (I Will Lead Them Up and Down)”. In recreating the scene in “Midsummer Night’s Dream” where the four lovers, Fairy Queen Titania and Bottom are all under the spell of a magic love potion administered by Fairy King Oberon and his assistant, Puck, Strayhorn groups the featured soloists in pairs: Hamilton (clarinet) and Nance (violin), Hodges (alto) and John Sanders (trombone), Procope (alto) and Gonsalves (tenor). In an inspired case of musical casting, Clark Terry (on flugelhorn) plays Puck. In contrast to the rest of the suite, Strayhorn’s writing is highly contrapuntal, with variations of the initial motive bouncing between the solo pairs while Terry improvises commentary with half-valve techniques and a plunger mute. At the end of the originally issued take, Terry speaks Puck’s famous line “Lord, what fools these mortals be” through his horn (more on this quote below). With all of the exotic atmosphere evoked by the Cleopatra movement, “Half the Fun”, it’s hard to believe that this piece was composed without any connection to Shakespeare. Ellington said that “the generally accepted theory [of Cleopatra’s encounter with Marc Antony] is that the mood was specific”. Johnny Hodges’ alto oozes mystical sexuality as does the enticing rhythmic pattern set by Woodyard. Strayhorn’s orchestration brings forth exotic sounds with its mixtures of clarinets and muted brass. Hodges’ ballad is the gorgeous “Star-Crossed Lovers”. The liner notes try to convince us that this is a duet between Hodges (as Juliet) and Gonsalves (as Romeo), but Gonsalves does not get any solo time on this track, so as some have said, it might have been better for Strayhorn to retain the original title (“Pretty Girl”) and state that it was Juliet’s lament for her young groom. Musically, the work creates harmonic instability with extensive use of chords built on the fourth and fifth scale degrees. Aside from the harmonic theory, it’s easy to appreciate Hodges’ rich alto tone and his sumptuous long glides between notes.

one that he wrote specifically for the suite is the delightful “Up and Down, Up and Down (I Will Lead Them Up and Down)”. In recreating the scene in “Midsummer Night’s Dream” where the four lovers, Fairy Queen Titania and Bottom are all under the spell of a magic love potion administered by Fairy King Oberon and his assistant, Puck, Strayhorn groups the featured soloists in pairs: Hamilton (clarinet) and Nance (violin), Hodges (alto) and John Sanders (trombone), Procope (alto) and Gonsalves (tenor). In an inspired case of musical casting, Clark Terry (on flugelhorn) plays Puck. In contrast to the rest of the suite, Strayhorn’s writing is highly contrapuntal, with variations of the initial motive bouncing between the solo pairs while Terry improvises commentary with half-valve techniques and a plunger mute. At the end of the originally issued take, Terry speaks Puck’s famous line “Lord, what fools these mortals be” through his horn (more on this quote below). With all of the exotic atmosphere evoked by the Cleopatra movement, “Half the Fun”, it’s hard to believe that this piece was composed without any connection to Shakespeare. Ellington said that “the generally accepted theory [of Cleopatra’s encounter with Marc Antony] is that the mood was specific”. Johnny Hodges’ alto oozes mystical sexuality as does the enticing rhythmic pattern set by Woodyard. Strayhorn’s orchestration brings forth exotic sounds with its mixtures of clarinets and muted brass. Hodges’ ballad is the gorgeous “Star-Crossed Lovers”. The liner notes try to convince us that this is a duet between Hodges (as Juliet) and Gonsalves (as Romeo), but Gonsalves does not get any solo time on this track, so as some have said, it might have been better for Strayhorn to retain the original title (“Pretty Girl”) and state that it was Juliet’s lament for her young groom. Musically, the work creates harmonic instability with extensive use of chords built on the fourth and fifth scale degrees. Aside from the harmonic theory, it’s easy to appreciate Hodges’ rich alto tone and his sumptuous long glides between notes.

In the opening act of “Hamlet”, the young prince is haunted by the ghost of his father, who claims that he was murdered by his brother, King Claudius. Hamlet decides to feign madness so that he can discover the truth without suspicion from his stepfather (Claudius) and his mother, Gertrude. Ellington’s setting of this episode, “Madness in Great Ones”, is one of his most of his most complex compositions, and a highlight of the album. It starts with an odd theme played by Carney and at least one of the trumpets. Just as the theme establishes its groove, a trombone interjection (taken up by the remaining trumpets) sets the whole thing askew, and within a few bars, there is a unique mixture of completing styles, including pyramid chords by the trumpets, a boogie figure by the trombones, and a Basie coda by Carney. The brass and reed sections seem to battle each other with diametrically opposing ideas until Hamilton’s clarinet initiates a fugue. About halfway through the track, Ellington introduces a brilliant motive: two or three of the trumpets play a dotted eighth pattern in 3/8 time that is performed against the rest of the band’s 4/4 swing beat. This use of polymeter is virtually unheard of in jazz, and I suspect that Ellington had been studying Stravinsky alongside Shakespeare. About two minutes into the track, lead trumpeter Cat Anderson makes his appearance as Hamlet. He plays a majestic figure which starts over the band but closes with an upward rip played without accompaniment. The other trumpets pick up the 3/8 figure again while Anderson shoots for higher and higher notes. The final notes he hits are above the range of a piccolo! This crazy quilt of music holds together exceptionally well, as if Ellington was quite sure that under the mask, Hamlet was sane all along.

As noted above, at the Town Hall premiere, “Cop-Out” was a last-minute finale to the suite. Both this piece and its replacement, “Circle of Fourths” were up-tempo blowing vehicles for Paul Gonsalves. “Cop-Out” was a minor blues with Gonsalves soloing against block chord commentary from the brass section. It is a solid piece of music that would have been a sufficient finale to the suite. However, Ellington and Strayhorn must have thought they could wrap up the Shakespeare suite with something both more exciting and more fitting to the subject. Someone made the connection between music’s circle of fourths and Shakespeare’s mastery of four dramatic forms (history, comedy, tragedy and romance—although Ellington usually substituted sonnets for romance in his announcements). Basically, the circle of fourths is the arrangement of keys in tonal music: start in any key and go up the interval of a perfect fourth to add a flat to the key signature and thus modulate to the next key in the series. Continue the process and you’ll eventually get back to the key where you started. For Ellington’s new finale “Circle of Fourths”, he had Gonsalves improvise over a chord sequence that modulated by fourths through all 12 keys in just over a minute and a half. The fast tempo and Gonsalves’ bravura performance makes ‘Circle of Fourths” a brilliant conclusion to the suite.

While the suite was recognized as one of Ellington and Strayhorn’s finest collaborations to date, Ellington only programmed a few of the movements in the band’s concerts. However, the band did play the complete suite live on at least two occasions. One was the performance at the 1957 Stratford festival. Ellington was not initially invited to return, but “Such Sweet Thunder” gave him additional leverage: The Stratford Festival are not repeating any of the jazz artists this year that they had last year. But I’ve already informed [them] that there’s one hazard in allowing us to do the Shakespearean suite… [W]e are liable to get publicity on it, which will sort of throw them into the position of having to be more or less graceful and inviting us back this year. An incomplete broadcast recording of the Stratford performance was recently unearthed. Ellington shuffled the order of the movements for this performance, notably moving the title movement into the second half, placing “Circle of Fourths” at the end of the first half, and closing the suite with “Madness in Great Ones”. The broadcast signal failed 55 seconds into “Circle of Fourths” and the problem was not fixed until the band was in the midst of “Sonnet in Search of a Moor”. No version of “Half the Fun” exists from this concert, and it is highly possible that it was played during the interruption of the broadcast.

For the other live performance, which took place at Chicago’s Ravinia Park on July 1, 1957, a radio broadcast (embedded below) has survived. It appears that the concert started about a half hour before the broadcast commenced. Ellington and the band were already halfway through the suite by that time, so when CBS radio cued him to start, the band played a brief reprise of the opening movement and then Ellington picked up where they left off in the concert. With the exception of transposing the order of “Sonnet for Sister Kate” and “Up and Down”, the band plays the second half of the suite in the same order as the LP. Musically, there are a few changes from the studio recording: Jackson adds a little growl on “Kate”, Terry plays his solos open on “Up and Down” (and Ellington rearranges the band on stage to spotlight the couples), Hodges uses dynamics to heighten the drama on “Star-Crossed”, Anderson’s coda on “Madness” is even more flamboyant and he shoots for higher notes than before, “Half the Fun” is played at a significantly faster tempo which makes it lose some of its unhurried exoticism, and Gonsalves’ solo on “Circle of Fourths” retains its excitement, despite a slower tempo.

In November 1957, Ellington and the band were back in Chicago to perform at the Blue Note. They were invited to appear on WGN-TV’s new culture series “World of Music”. Included within the hour-long performance were three movements from “Such Sweet Thunder”: the title track, “Lady Mac” and “The Telecasters” (incidentally, all of these tracks were from the first side of the LP, so with the Ravinia broadcast, we have live performances of most of the suite). On the previous month’s broadcast, Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony performed Berlioz’s “Queen Mab” scherzo from “Romeo and Juliet”; the show’s host links the Berlioz and Ellington settings by noting their differences but not judging one as superior to the other. Ellington’s propensity to increase tempos in live performances appears here, with the suite’s title movement taken so briskly that the swagger so prominent in the original recording is nearly gone (he also omits the “doomsday motive” at the end). “The Telecasters” plays basically the same as on the recording, and “Lady Mac” retains her grace even at a slightly faster tempo.

The original Columbia LP was recorded in both mono and stereo, yet until 1999, only the mono version was issued. The stereo LP was listed in catalogues and advertised, but the project was mysteriously abandoned in November 1957. For the long-awaited CD reissue, producer Phil Schaap restored (almost) all of the original tracks in their stereo versions. The results are stunning: the sound is full, spacious and well-balanced between the two channels. In a tedious liner essay, Schaap claims that the reason the stereo LP was abandoned not because of the music, but because of the ambience (room sound) between the tracks! To get the effect that the original producer Irving Townsend wanted, the musicians had to remain still for several seconds after the music ended—and Schaap claims that Ellington’s band couldn’t do that (in an audacious quote, Schaap writes “In short, the New York Philharmonic cut the Duke Ellington Orchestra when it came to keeping quiet”). This theory is utter nonsense. For years, musicians have known that they had to keep quiet for a few seconds after recording a take, and to say that Ellington’s band couldn’t do that amounts to a blatant insult. Even if they didn’t know this basic rule, all Townsend would have had to do was remind the musicians before they started recording. Further, Ellington or Strayhorn could have held their palm out (like a policeman directing traffic) to signal the musicians to hold their places once the music ended. At any rate, the ambience is virtually inaudible on the original LP record, as it is masked by surface noise. It can be heard on the CD, but the effect only comes through when listening with headphones.

So why didn’t Columbia issue the stereo LP as advertised? The answer probably lies within another mistake on the CD. The mono take of “Up and Down” was take 12; the stereo was take 1. The actual takes are not terribly different, except for one crucial point: on the stereo take, Clark Terry plays a flurry of notes over the final chord instead of intoning Puck’s quotation. This leads us to two conclusions. First, in between takes 1 and 12, someone—probably Ellington or Strayhorn—asked Terry to “say” the quote through his horn using half-valve effects. Terry agreed, and the quote became a permanent part of the arrangement. Second, something must have gone wrong with the stereo tape recorder during this time, because Columbia obviously didn’t have a stereo take with Terry’s Puck quote. Two of the other tracks would have had alternate takes for the stereo LP, but with the Puck quote specifically mentioned in the album’s liner notes, Columbia probably realized that they could not get away with issuing a stereo version that did not contain the quote. Moving ahead to the CD reissue, I find it very hard to believe that no one on the production team listened to this stereo master and recognized the obvious error. Schaap could have simply admitted that the stereo take of “Up and Down” was the only one available, and then inserted the originally issued mono take as a bonus track. As it stands, collectors need to hold on to their old mono LPs (or buy one from a used dealer) to have the correct take of “Up and Down”.

The bonus section of the CD is a mixed bag. There are the stereo alternates of “Star-Crossed Lovers” and “Circle of Fourths” alluded to above, plus an alternate of “Half the Fun” and a nine-minute sequence of takes of the original recording of “Star-Crossed Lovers” (when it was still titled “Pretty Girl”). However, Schaap also includes multiple takes of three tunes recorded at the same sessions, but which have no relationship to the Shakespeare suite. I can understand the rationale of issuing these tracks on the CD since they stand little chance of being issued elsewhere, but not when the space could be better used to include music that is directly related to the main album. For example, the original finale to the suite, “Cop-Out” was recorded in March 1957 and was issued on a 45 single. Why was that track not included on the CD? And while the Ravinia broadcast had not yet been discovered in 1999, the WGN “World of Music” broadcast had been available on an unauthorized LP since 1990 or earlier. Where were those tracks?

With all of these important supplemental recordings now available, I think it’s time for Sony Music to reissue “Such Sweet Thunder” in a definitive CD set. As owner of some of the undisputed classics of American music, Sony has a responsibility to keep this music available to the general public. Several of the Schaap-produced discs are flawed, including “Such Sweet Thunder” and the tinny sounding Benny Goodman Carnegie Hall Concert. Jazz fans should not have to buy foreign reissues—most of which do not originate from the master recordings—just to get properly made digital versions of their favorite albums. It’s time to give these jazz masterpieces the treatment they deserve.