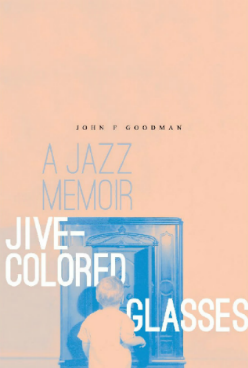

Up until a few years ago, John F. Goodman’s best-known work in jazz journalism was his nine-year tenure as the music critic for Playboy magazine. Prior to that, Goodman had also written for The New Leader, but most of his career was spent teaching English at various universities, and writing for educational and union organizations. Jazz has been a passion for Goodman ever since his childhood, and in 2012 Goodman returned to his jazz roots when he wrote and compiled “Mingus Speaks”, a series of rough-and-tumble interviews with Charles Mingus. Three years later he has self-published a memoir, “Jive Colored Glasses” and while his non-musical experiences are included, the theme of jazz acts as a running background.

Up until a few years ago, John F. Goodman’s best-known work in jazz journalism was his nine-year tenure as the music critic for Playboy magazine. Prior to that, Goodman had also written for The New Leader, but most of his career was spent teaching English at various universities, and writing for educational and union organizations. Jazz has been a passion for Goodman ever since his childhood, and in 2012 Goodman returned to his jazz roots when he wrote and compiled “Mingus Speaks”, a series of rough-and-tumble interviews with Charles Mingus. Three years later he has self-published a memoir, “Jive Colored Glasses” and while his non-musical experiences are included, the theme of jazz acts as a running background.

Goodman was born in 1935 to a prosperous Jewish family in Chicago. Goodman’s father worked in upper management for Florsheim Shoes, and while he claimed to his family (and presumably others) that “this family is like everybody else…just average, ordinary people”, the Goodman family lived in a large house in the suburbs and held several trust funds. Goodman’s father was also a big band fan, and young John first identified his favorite recordings from his father’s collection by the colors of the record labels. In 1950, Goodman père hosted a house concert by Louis Armstrong and his All-Stars! John, 15 years old at the time, was mesmerized by both the music and the men who played it. He recalls several of the tunes that the band played at the concert (including “Black and Blue”, the lyrics of which are reprinted in the book) and the attitudes of the two best-known musicians: Earl Hines didn’t say much to anyone, and Jack Teagarden sported a large case which held his trombone, a clean shirt and a spare bottle of gin. John was already a fan of New Orleans jazz, and in a particularly eloquent passage, he tells of how he first heard the music and how his love of jazz intersected with his father’s. A few years after the Armstrong concert, John discovered bebop. His father never really felt any enthusiasm for bop, but in later chapters, John relates how he brought other family members to modern jazz concerts, usually to positive reactions.

Goodman is quite skilled at finding the essence of jazz, and showing how it relates to other arts. He quotes his perceptive 1969 review of Chick Corea’s album “Now He Sings, Now He Sobs”, which includes comparisons to the music of composer John Cage. In the final chapter of his book, he makes several stunning connections between jazz and Marcel Proust’s “Remembrance of Things Past”. Later in that same chapter, Goodman makes several astute comments about the state of jazz today, noting his personal dislike of free jazz, and making an incisive criticism of a multicultural Vijay Iyer recording (and New York Times reviewer Ben Ratliff’s critique of it). His statements on basic jazz history can raise eyebrows: when discussing Bud Powell he makes an odd comparison to Powell’s right hand style with “Art Tatum playing stoned”, a simile that does neither artist any favors. He also claims that Powell’s harmonic sense came out of the Billy Eckstine and Dizzy Gillespie big bands, when it’s much more likely that those developments were the results of after-hours sessions at Minton’s, Monroe’s and the parlor of Mary Lou Williams. Two paragraphs later, he acknowledges that Thelonious Monk played a crucial role in developing bebop, but instead of addressing those developments, Goodman writes that “Monk went on to do his own thing” and leaves it at that. What is most surprising about these statements is that Goodman’s comments later in the book show that he has a decent understanding of modern jazz. The above statements seem to steer the reader in the wrong direction, without any good reason.

Goodman portrays himself as something of a rebel, and to be sure, his writing style takes more than a few unexpected turns. He relies on his excellence as a storyteller to navigate large chronological jumps as he discusses his relationship with his parents. He leaves out several details, including his actual birth date, his graduation from college and his first teaching jobs. He provides way too much detail about his spouses, girlfriends, and his sex life, but when it comes to discussing famous jazz venues like Slug’s, he includes an extended quote from fellow jazz author James Gavin instead of describing the atmosphere himself. Unfortunately, one of the side effects of today’s world of self-publishing is that manuscripts are published without thorough editing. However, there is one advantage to writing about music in today’s environment: readers who purchase the e-book version of Goodman’s memoir will find hyperlinks throughout the manuscript which take the reader to YouTube clips of the original tracks. For readers new to the music of Louis Armstrong, Charlie Parker, Bud Powell, Art Tatum, Charles Mingus and other jazz greats, this interactive feature can make these classic recordings come alive.