Columbus Calvin “Duke” Pearson, Jr. was born in Atlanta, Georgia on August 17, 1932. Tagged with the nickname “Duke” by his Ellington-loving uncle, Pearson played piano until the age of twelve. He developed a deep passion for brass instruments, and through most of his teens and early twenties he neglected the piano and studied trumpet. It wasn’t until 1959, when he met Wynton Kelly, that he again turned his attention to the piano. Over the course of the next ten years, Pearson would enjoy the most productive phase of his career, arranging tunes for Donald Byrd, touring with Nancy Wilson and was the A & R man on a number of Blue Note recordings (with Carmen McRae, Grant Green and Bobby Hutcherson).

Columbus Calvin “Duke” Pearson, Jr. was born in Atlanta, Georgia on August 17, 1932. Tagged with the nickname “Duke” by his Ellington-loving uncle, Pearson played piano until the age of twelve. He developed a deep passion for brass instruments, and through most of his teens and early twenties he neglected the piano and studied trumpet. It wasn’t until 1959, when he met Wynton Kelly, that he again turned his attention to the piano. Over the course of the next ten years, Pearson would enjoy the most productive phase of his career, arranging tunes for Donald Byrd, touring with Nancy Wilson and was the A & R man on a number of Blue Note recordings (with Carmen McRae, Grant Green and Bobby Hutcherson).

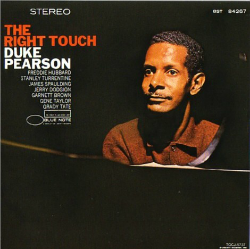

Of the seventeen albums Duke Pearson recorded during his 10-plus years as a bandleader, “The Right Touch” was his crowning achievement. The record showed the world that Pearson’s playing could be as deft and delicate as Duke Ellington or as harmonically rich as Bill Evans. The six tunes on the album demonstrated the breadth of Pearson’s compositional skills, offering music that drew from early blues, Latin jazz and late bebop. Recorded on September 13, 1967 at the Van Gelder Studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, “The Right Touch” was Pearson’s tenth recording as a leader. Over the rhythm section of Pearson, bassist Gene Taylor and drummer Grady Tate, Freddie Hubbard and Garnett Brown acted as brass section and saxophonists Stanley Turrentine (tenor), James Spaulding (alto) and Jerry Dodgion (alto and flute) rounded out the personnel.

The opener, “Chili Peppers,” is a pulsing seven minute Latin jazz piece that blends the East Coast aggressiveness of Charles Mingus with the easy-going West Coast swing of Stan Getz. After a quick two-bar opening riff, Pearson, Tate and Taylor settle into an energetic samba riff, setting the table for the horns to feast on the tune’s verse and chorus figures. Turrentine gets the first taste of the spotlight, dropping a solo that’s by turns honking bop and melodic pop. Pearson chooses to stay in the middle of the keyboard for his turn, taking a chunky, chordal approach to his sixty-four bars. The cut ends on a sly and subtle note, with the horn section repeating a spry four note figure over a quick fade out. “Make It Good” is straight Ellingtonian swing, a feature piece for Pearson who dives headlong into his solo section right at the top of the number. Pearson shows a deft and delicate touch as he glides over the instrument’s upper register. Hubbard takes his first solo here with an homage to Miles Davis, playing in a sparse, angular, deceptive style. Taylor’s bass is rich, organic and substantial while Tate’s playing is effective and swinging without being overbearing. Once again, a sly repeating figure closes the tune with a subtle fade out. Hubbard kicks off “My Love Waits,” a seductive, low key Latin lounge piece, pushed along by Tate’s brush-and-cross-stick rhythm pattern and accentuated by smokey chord figures from the rest of the horn section. Hubbard is typically charming here, with a warm, round tone that stays right in the center of the instrument’s sweet spot. Pearson plays it cool here, as well, repeating the melodic solo approach he took on “Make It Good.”

Whatever solace the listener might feel from “Make It Good” is immediately broken by the fast, furious electricity of “Los Malos Hombres.” Hubbard blows hard here, insistent and cajoling, while Spaulding sees the spotlight for the first time, his approach at times arching, at times jagged, at times emulating John Coltrane‘s “A Love Supreme“. Tate’s only solo is on this piece, his rapid fire left hand skittishly jumping across the snare drum throughout his time alone. The straight slow blues piece, “Scrap Iron” is all gospel horn riffs, Pearson playing coy and Tate feeling woozy, not entirely locked into 12/8, playing about with a bit of 4/4, as well, as the mood seems to strike him. Turrentine is dark and dirty, sometimes growling, sometimes yearning, his solo an eminently thoughtful portrayal of a man alone with the blues. The album comes full circle with the closing cut, “Rotary.” It’s the biggest band arrangement on what is otherwise a small band album. Hubbard leans into his solo with a needful urge to break loose, sounding a bit antsy, as if he’s restraining himself. Tate swings looser here than elsewhere on the album, playing around the beat a bit more while Brown makes the most of his one trombone solo. While nothing here is earth-shattering by historical standards, “The Right Touch” demonstrates the many facets of Pearson talent, and it proved that he was worthy of greater attention as a player and arranger.

Editor’s note: This review refers to the LP version of this album; the digital version (linked above) also includes an alternative take of “Los Malos Hombres”.