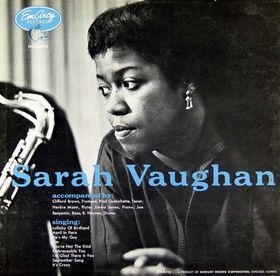

Around Christmas 1951, Sarah Vaughan was headlining at New York’s Café Society. Also on the bill was a rhythm and blues group from Philadelphia called Chris Powell and His Blue Flames. Vaughan listened to the group while she was offstage and was very impressed with Powell’s newest band member, a 22-year old unrecorded trumpeter named Clifford Brown. Vaughan and Brown discussed making a recording together, but it would be nearly three years before the sessions took place. Vaughan was recording for Columbia in 1951, and one of her recent albums featured Miles Davis, so Columbia was probably not too keen on pairing with another jazz trumpet player. Instead, she recorded several pop sides for Columbia until her contract expired in early 1953. About a year later, she signed an unusual deal with Mercury, recording pop sides for the parent label, and jazz for the subsidiary, EmArcy. By the time Vaughan and Brown collaborated on record, both were recording for EmArcy, and Brown had become one of the most popular young jazz trumpeters on the scene. Originally titled “Sarah Vaughan” (and later repackaged to promote Brown’s presence), the album was Vaughan’s second jazz date for the label and her first recording for 12-inch LPs.

Around Christmas 1951, Sarah Vaughan was headlining at New York’s Café Society. Also on the bill was a rhythm and blues group from Philadelphia called Chris Powell and His Blue Flames. Vaughan listened to the group while she was offstage and was very impressed with Powell’s newest band member, a 22-year old unrecorded trumpeter named Clifford Brown. Vaughan and Brown discussed making a recording together, but it would be nearly three years before the sessions took place. Vaughan was recording for Columbia in 1951, and one of her recent albums featured Miles Davis, so Columbia was probably not too keen on pairing with another jazz trumpet player. Instead, she recorded several pop sides for Columbia until her contract expired in early 1953. About a year later, she signed an unusual deal with Mercury, recording pop sides for the parent label, and jazz for the subsidiary, EmArcy. By the time Vaughan and Brown collaborated on record, both were recording for EmArcy, and Brown had become one of the most popular young jazz trumpeters on the scene. Originally titled “Sarah Vaughan” (and later repackaged to promote Brown’s presence), the album was Vaughan’s second jazz date for the label and her first recording for 12-inch LPs.

The album was recorded in two sessions during December 1954. Vaughan’s working trio of pianist Jimmy Jones, bassist Joe Benjamin and drummer Roy Haynes, was augmented by Brown, tenor saxophonist Paul Quinichette and flutist Herbie Mann. Mann was a busy New York session player during this time. He had heard about Brown as early as 1949, and was ecstatic when Quincy Jones—an old friend of Brown’s—secured him a place on the Vaughan date. Quinichette was one of Lester Young’s most ardent disciples, and was dubbed “Vice-Pres” for his dedication to Young’s style. Neither Mann nor Quinichette was a top-flight improviser at the time, but being in the presence of Vaughan and Brown inspired them to some of their finest recorded work to that time. Vaughan claimed that Brown knew none of the songs that she and arranger Ernie Wilkins had prepared for the album, but he certainly knew “Lullabye of Birdland”, and was probably familiar with “April in Paris” and “September Song”. In any case, Brown was intrigued with the repertoire, as witnessed by an unissued practice tape I heard while visiting Brown’s widow, LaRue. On it, Brown improvised new solos while his recorded solos from this album played on a phonograph.

“Lullabye of Birdland” opens the album, and it features Vaughan’s only scat solos of the date. She improvises four-bar phrases against the horns, and in the only alternate take of the date, we can hear Vaughan and the band in an earlier attempt at the solo section. “April in Paris” gets an elegant treatment with Vaughan singing an exquisite first chorus supported only by Jones, and a cup-muted Brown offering perfectly modulated responses in Vaughan’s second chorus. “He’s My Guy” has Vaughan at her sassiest, a swinging chorus by Quinichette, glorious open trumpet by Brown, and tasty piano from Jones. The last chorus is a total delight, with Vaughan sliding around the melody while the horns support her with a groovy little riff. “Jim” was a little-recorded tune when Vaughan and Brown made their version, and the excellence of this recording has kept many other singers from attempting it. It’s hard to imagine anyone topping this rendition, with Vaughan’s heartfelt delivery and Brown’s eloquent solo, but when I heard expatriate American Sara Lazarus sing it at the Paris nightclub New Morning, it was clear that everyone in the room knew the Vaughan recording note-for-note, and Lazarus carefully avoided Vaughan’s melodic and rhythm variations without losing the spirit of the original recording, When the first chorus ended, we nearly expected to hear a new solo by Clifford Brown.

The glowing sound of Brown’s trumpet opens the second side with “You’re Not the Kind”. The rhythm section locks into a tight swinging groove, and Vaughan uses her elastic sense of rhythm in the opening chorus. Quinichette rides the rhythm like Young, Mann has good ideas, but his anemic tone is no match for Brown’s rich tone. And what a solo Brown plays, dotted with beautifully executed double-time and great melodic sequences. Vaughan’s final chorus is a brilliant melodic variation, and in the coda, she nails a chromatic sequence that had given her trouble in a previous recording. In a cruel irony, that earlier version featured the young bop trumpeter Freddie Webster, who died less than two years after the recording; when Clifford Brown died eighteen months after this recording, Vaughan removed the song from her repertoire and never recorded it again. “Embraceable You” features Vaughan with the trio, and she performs a remarkable variation on the Gershwin melody. The lyrics of “September Song” take on extra poignancy considering Brown’s early (and accidental) passing, but the trumpeter’s double-time solo lightens the funereal mood. Vaughan includes the oddly-measured verse to “I’m Glad There Is You”, and her entrance to the chorus is the only place where her ornamentation seems overdone. No such complaints from that point on, though—her final half-chorus contains more breathtaking variations. This was a special song for Brown, as the sentiments of the lyric expressed his feelings about his new bride, who was sitting in the studio as they made this recording. The album closes with the light-hearted “It’s Crazy”, which inspires Brown’s fieriest solo of the date and a Quinichette solo that opens with a quote from Lester Young’s solo on “Jive At Five”.

The music recorded on those two winter days more than a half-century ago remains vibrant and alive, even though all but one of the participants have passed on. Only Roy Haynes survives, and he may be even more creative today than in the mid-50s. The rest created great music in their remaining days, with Vaughan’s voice and artistry growing more profound as her career continued. Even Clifford Brown topped himself repeatedly with only a year and a half left to create. His recordings with Max Roach and Sonny Rollins remain unquestioned jazz masterpieces, with the extraordinary musical communication between the principals adding spark to their inventive music. Quinichette recorded several fine albums, including a collaboration with John Coltrane, and Mann’s music was a commercial success in the sixties and seventies. Jones was in constant demand as a vocal accompanist (including stints with Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald and Shirley Horn), and Benjamin toured with Dave Brubeck and Ellington. The plainly-titled album “Sarah Vaughan” has been properly acclaimed as one of the finest vocal albums ever made. Yet in a sense, it is more profound than that: it represents a high point from musicians who would find even greater heights to conquer.