George Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess” lives in two separate worlds. It is an  opera, yet it premiered in a Broadway theatre. Its premiere run was for 124 performances—a flop by Broadway standards, but an impressive record for a contemporary American opera. Gershwin composed the work in the established style of European grand opera, but the music reflected the American genres he loved: jazz, blues, ragtime, folk songs, and black sacred music. He was criticized for including “hit songs” into a serious opera, but those songs became the work’s greatest legacy. In addition to creating an indigenous sound for American opera, the music from “Porgy and Bess” was performed by jazz and pop musicians all over the world, and it was loved by audiences who had never seen the opera in its stage or film versions.

opera, yet it premiered in a Broadway theatre. Its premiere run was for 124 performances—a flop by Broadway standards, but an impressive record for a contemporary American opera. Gershwin composed the work in the established style of European grand opera, but the music reflected the American genres he loved: jazz, blues, ragtime, folk songs, and black sacred music. He was criticized for including “hit songs” into a serious opera, but those songs became the work’s greatest legacy. In addition to creating an indigenous sound for American opera, the music from “Porgy and Bess” was performed by jazz and pop musicians all over the world, and it was loved by audiences who had never seen the opera in its stage or film versions.

George Gershwin first read DuBose Heyward’s 1925 novel “Porgy” in a single sitting. Heyward was a novelist from Charleston, South Carolina, who based his title character on Sammy Smalls, a crippled black beggar known as “Goat Cart Sammy” for his primary mode of transportation. Smalls had died or disappeared by the time Heyward wrote his book, but Heyward knew Smalls’ neighborhood well: it was called Cabbage Row and it was not far away from Heyward’s home. Heyward and his mother had studied the Gullah culture practiced in Cabbage Row (renamed Catfish Row for the novel and all later adaptations). After Heyward had successfully captured the atmosphere in his novel, his new wife, Dorothy, adapted the novel into a stage play. Gershwin approached Heyward with the idea of an opera around 1928, but he didn’t start composing the opera for another five years. At Heyward’s insistence, Gershwin spent several months in South Carolina learning and absorbing the Gullah culture for himself, becoming quite skilled at “shouting” in black church services.

The opera’s libretto was written jointly by DuBose and Dorothy Heyward, with significant lyric contributions by Ira Gershwin. The Gershwins and their estate have always insisted on all-black casts in English-language productions of “Porgy and Bess”, and with the lack of integrated opera companies at the time, Broadway seemed a logical place to stage the new work. The first performance in Boston ran nearly four hours, and Gershwin started the arduous process of cutting the work down. However, a vocal score was created during this period, preserving pieces of music that never played on the Broadway stage. The New York premiere was on October 10, 1935 at the Alvin Theatre and the show closed on January 26, 1936. A month later, Bob Crosby’s band was using “Summertime” as its theme song, and in July, Billie Holiday became the first jazz vocalist to record it.

Tom Lord lists over 1700 recorded versions of “Summertime” in his online “Jazz Discography”, but this study does not deal with the isolated jazz recordings of that song or any others from “Porgy and Bess”. Rather, we will examine several concept albums which present “Porgy and Bess” as a total entity. Some of these recordings follow the original song sequence from the score, but even the most complete jazz version does not include all of the music. The synopsis here provides the opera’s original storyline, characters and song sequence. The synopsis will open in a separate window, and we highly recommend keeping it open for reference while reading the essay.

The first album-length jazz adaptation of “Porgy and Bess” was also the most  elaborate. Bethlehem’s all-star recording was originally issued as a 3-LP set, and presented the opera with nearly all of its themes and dramatic action intact. Only the recitatives and a few minor arias were cut, and the gaps were filled with narration. It was an audacious project for an independent label to undertake, but Bethlehem’s roster had a deep talent pool and nearly all of their artists took part in this album. Mel Tormé was the biggest star on the label and his interpretation of Porgy holds this production together. He sings the part with great feeling and superb musicianship. His version of “They Pass by Singin’” imbues all of the loneliness contained in his character. Playing opposite Tormé is Frances Faye as Bess. Faye is nearly forgotten today, but she was one of the first flamboyantly bisexual performers in show business. She performed in cabarets and her vocal style was a loud mixture of shouting and singing. She was chosen to play Bess because she shared the character’s tough demeanor. However, Bess’ character goes through a great transformation in the course of the opera, and Faye was unable to communicate those dramatic changes. When Faye bellows “Porgy, I’s Your Woman Now”, it sounds more like a threat than a declaration of love.

elaborate. Bethlehem’s all-star recording was originally issued as a 3-LP set, and presented the opera with nearly all of its themes and dramatic action intact. Only the recitatives and a few minor arias were cut, and the gaps were filled with narration. It was an audacious project for an independent label to undertake, but Bethlehem’s roster had a deep talent pool and nearly all of their artists took part in this album. Mel Tormé was the biggest star on the label and his interpretation of Porgy holds this production together. He sings the part with great feeling and superb musicianship. His version of “They Pass by Singin’” imbues all of the loneliness contained in his character. Playing opposite Tormé is Frances Faye as Bess. Faye is nearly forgotten today, but she was one of the first flamboyantly bisexual performers in show business. She performed in cabarets and her vocal style was a loud mixture of shouting and singing. She was chosen to play Bess because she shared the character’s tough demeanor. However, Bess’ character goes through a great transformation in the course of the opera, and Faye was unable to communicate those dramatic changes. When Faye bellows “Porgy, I’s Your Woman Now”, it sounds more like a threat than a declaration of love.

Clara is played by Betty Roché, a former vocalist for the Duke Ellington band. Roché had a seductive vocal style and her version of “Summertime” sounds like its being directed to a man instead of a baby, but her scat solos later in the set are delightful and inventive. Frank Rosolino sings the part of Jake. His quirky vocal style works well on the light-hearted “A Woman Is a Sometime Thing”, but a little hard to believe on the work song “It Takes a Long Pull to Get There”. Impressionist George Kirby is serviceable as Sportin’ Life, and Sallie Blair sings a throbbing version of “My Man’s Gone Now” as Serena, but the big surprise is Johnny Hartman as Crown. Best known as a romantic singer, Hartman adds a rough edge to his sound and makes the part his own. He carries the dramatic tension in his duet with Faye, “What You Want Wid Bess” and struts his way through the blues-inspired “A Red-Headed Woman”. The choral parts throughout are sung by the Pat Moran Quartet, and while they sing well as a group, their style sounds hopelessly dated today.

The connecting narration was penned by a CBS script writer Al Moritz, and read by disc jockey Al “Jazzbeaux” Collins. Collins does his best to infuse enthusiasm into the script, but he doesn’t have much to work with, and the liner notes imply that Moritz’ script was pruned to fit within the time limits of the recording. Russ Garcia adapted and conducted the music, and his arrangements included spots for the Australian Jazz Quintet and a small jazz group led by Stan Levey, as well as full orchestra (There was a previously recorded version of “Summertime” by Duke Ellington inserted into the album, and that was the only arrangement not written by Garcia). As with several arrangers discussed in this study, Garcia took many liberties with Gershwin’s score, but included several of the original countermelodies in his settings.

In his autobiography, Tormé wrote that he hated the Bethlehem recording because the “polyglot” approach belittled the original material. To be sure, the Bethlehem version has many flaws, but in its attempt to present the entire work (albeit in abbreviated form), it inspired many other jazz artists to explore Gershwin’s rich score. The flood of jazz “Porgy and Bess” albums in the late 50s can also be traced to two other sources: the popularity of jazz adaptations of Broadway shows, starting with Shelly Manne’s hit album of songs from “My Fair Lady”, and the highly-publicized film version of “Porgy and Bess”, produced by Samuel Goldwyn, and starring Sidney Poitier, Dorothy Dandridge, Sammy Davis, Jr. and Pearl Bailey. In 1959, as the film was being prepared for release, nearly every existing record company had a version of “Porgy and Bess” for sale. The film itself was criticized for adapting the original material into a standard movie musical style. When the film’s copyright expired, the Gershwin estate had the film withdrawn, and they have attempted to destroy all existing prints.

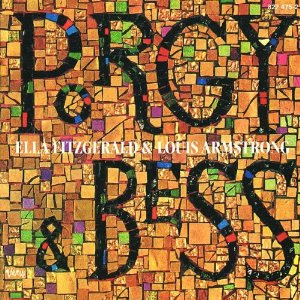

One of the most popular approaches in creating album-length versions of “Porgy and Bess” was to match a male and female vocalist, and have each singer perform all of the parts of their respective gender. The backing arrangements would be for big band or full orchestra, and tailored for the featured artists. Such was the case with the Norman Granz-produced recording featuring Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald. Granz gave the album the “deluxe treatment” with extensive liner notes and striking cover art. However, most of the music on the 2-LP set was recorded in a single marathon session, with little time for second takes or rehearsals. Of course, Armstrong, Fitzgerald and the studio orchestra, led—once again—by Russ Garcia, were used to working with Granz, and were up for the challenge. Armstrong and Fitzgerald’s beautifully-nuanced version of “Summertime” reportedly brought tears to the eyes of Ira Gershwin, and if Fitzgerald’s rendition of “My Man’s Gone Now” lacks a sense of repressed anger, it is a heartfelt evocation of melancholy. Armstrong relishes the lyric of “A Woman Is a Sometime Thing” and makes us want to join him on a “Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York”. The spirit is there for “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’”, but Armstrong botched a key lyric—“the folks with plenty of plenty” have “nuttin’” in his reading—and the resulting confusion of the message should have signaled a retake. Fitzgerald asked to sing “It Ain’t Necessarily So” with Armstrong, and her reading of the lyric is delightfully slinky and a great contrast to Armstrong’s majestic trumpet and straight (for him) singing. Both get the chance to scat in the interludes, and later, when Fitzgerald sings about Methuselah, Armstrong improvises the hilarious response “Ol’ ‘Thusie”. One of the most beloved versions of “Porgy and Bess”, the Armstrong/Fitzgerald album finds the two principals in top form. While the album might have benefited from more rehearsal and recording time (I wish that Armstrong would have sung the counter melody on “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” instead of scatting his own line), the natural chemistry between Ella and Louis makes this album a classic.

One of the most popular approaches in creating album-length versions of “Porgy and Bess” was to match a male and female vocalist, and have each singer perform all of the parts of their respective gender. The backing arrangements would be for big band or full orchestra, and tailored for the featured artists. Such was the case with the Norman Granz-produced recording featuring Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald. Granz gave the album the “deluxe treatment” with extensive liner notes and striking cover art. However, most of the music on the 2-LP set was recorded in a single marathon session, with little time for second takes or rehearsals. Of course, Armstrong, Fitzgerald and the studio orchestra, led—once again—by Russ Garcia, were used to working with Granz, and were up for the challenge. Armstrong and Fitzgerald’s beautifully-nuanced version of “Summertime” reportedly brought tears to the eyes of Ira Gershwin, and if Fitzgerald’s rendition of “My Man’s Gone Now” lacks a sense of repressed anger, it is a heartfelt evocation of melancholy. Armstrong relishes the lyric of “A Woman Is a Sometime Thing” and makes us want to join him on a “Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York”. The spirit is there for “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’”, but Armstrong botched a key lyric—“the folks with plenty of plenty” have “nuttin’” in his reading—and the resulting confusion of the message should have signaled a retake. Fitzgerald asked to sing “It Ain’t Necessarily So” with Armstrong, and her reading of the lyric is delightfully slinky and a great contrast to Armstrong’s majestic trumpet and straight (for him) singing. Both get the chance to scat in the interludes, and later, when Fitzgerald sings about Methuselah, Armstrong improvises the hilarious response “Ol’ ‘Thusie”. One of the most beloved versions of “Porgy and Bess”, the Armstrong/Fitzgerald album finds the two principals in top form. While the album might have benefited from more rehearsal and recording time (I wish that Armstrong would have sung the counter melody on “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” instead of scatting his own line), the natural chemistry between Ella and Louis makes this album a classic.

Two further examples of the dual-vocalist approach should be mentioned here.  Sammy Davis, Jr. played Sportin’ Life in the Goldwyn film. He was under contract to Decca, who did not allow Columbia to use Davis’ film tracks for the soundtrack album, so Cab Calloway subbed for Davis on Columbia, and Decca made their own “Porgy and Bess” album with Davis and Carmen McRae. McRae’s solo versions of “Summertime” and “My Man’s Gone Now” are faithful to the opera, even including the original arrangements. Davis’ solos, which constitute the majority of the album, sound like Vegas-cum-Hollywood versions of the songs, with flashy arrangements, and Davis’ pseudo-hipster finger snaps and vocal asides. “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” is the only McRae/Davis duet, and the sound of the recording makes me suspect that the vocals were recorded separately. Better overall

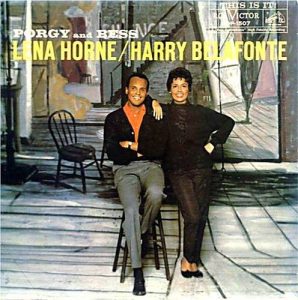

Sammy Davis, Jr. played Sportin’ Life in the Goldwyn film. He was under contract to Decca, who did not allow Columbia to use Davis’ film tracks for the soundtrack album, so Cab Calloway subbed for Davis on Columbia, and Decca made their own “Porgy and Bess” album with Davis and Carmen McRae. McRae’s solo versions of “Summertime” and “My Man’s Gone Now” are faithful to the opera, even including the original arrangements. Davis’ solos, which constitute the majority of the album, sound like Vegas-cum-Hollywood versions of the songs, with flashy arrangements, and Davis’ pseudo-hipster finger snaps and vocal asides. “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” is the only McRae/Davis duet, and the sound of the recording makes me suspect that the vocals were recorded separately. Better overall  was RCA’s album featuring Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne. Belafonte refused the role of Porgy in the Goldwyn film, and Horne was never asked—by Goldwyn or anyone else—to play Bess. Horne’s thrilling performances on “My Man’s Gone Now” and “I Loves You, Porgy” show that she would have been anexceptional Bess, and judging from her sly version of “It Ain’t Necessarily So”, she could have played Sportin’ Life, too! Belafonte sings his selections in a wonderfully relaxed manner, working exceptionally well with the big band settings. He is also suitably intense on the medley of street vendor calls. Belafonte and Horne sing together on the side closers, “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” and “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York”. Unfortunately, the placement of “Boat” at the end of the album might lead listeners unfamiliar with the opera to believe that at the finale, Porgy and Bess travel together to New York to find greater fortunes. While the opera’s third act is dramatically weak as it is, this imagined ending is far worse!

was RCA’s album featuring Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne. Belafonte refused the role of Porgy in the Goldwyn film, and Horne was never asked—by Goldwyn or anyone else—to play Bess. Horne’s thrilling performances on “My Man’s Gone Now” and “I Loves You, Porgy” show that she would have been anexceptional Bess, and judging from her sly version of “It Ain’t Necessarily So”, she could have played Sportin’ Life, too! Belafonte sings his selections in a wonderfully relaxed manner, working exceptionally well with the big band settings. He is also suitably intense on the medley of street vendor calls. Belafonte and Horne sing together on the side closers, “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” and “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York”. Unfortunately, the placement of “Boat” at the end of the album might lead listeners unfamiliar with the opera to believe that at the finale, Porgy and Bess travel together to New York to find greater fortunes. While the opera’s third act is dramatically weak as it is, this imagined ending is far worse!

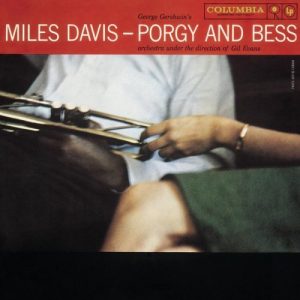

Gil Evans once called Miles Davis “a great singer of songs”. The vocal quality  of Davis’ trumpet style had been glimpsed in several earlier recordings (including the Evans-arranged version of “My Ship” on “Miles Ahead“), and it was the focus of the Davis/Evans collaboration on “Porgy and Bess”. Like a great opera singer, Davis is at center stage, surrounded by Evans’ richly colored orchestrations. There is little that can prepare the listener for the screaming intensity of the trumpets on the opening track, “Buzzard Song”, or the sheer power at the climax of “My Man’s Gone Now”. And while Evans has jettisoned Gershwin’s original orchestrations and tune sequence, he has created splendid original music of his own, including the jaunty tuba/bass line on “Buzzard”, the nearly-iconic counter melody on “Summertime” and the fast, straight-ahead variant on the funeral theme “Gone”. And could anyone but Miles Davis offer such a wide range of emotions without uttering a single word? He makes these songs personal, and that engages us as listeners. There are many other wonders to this recording: Evans’ acute dramatic sense (notice that the climax of “My Man’s Gone Now” is only a few bars, but its effect carries on much longer), Davis’ unique approach to modal improvisation (still a new concept in jazz at the time), and the glimpses of other “Porgy” arias inserted into the improvisations and arrangements (The notes mention the interpolation of “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’” at the beginning of “It Ain’t Necessarily So”, but I doubt that many recognize “They Pass By Singin’” as the intro to “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” or the reprise of the “Gone” motive near the end of “Boat”). An album that truly rewards repeated listening, the Davis/Evans version of “Porgy and Bess” is a brilliant transformation of Gershwin’s score, and a stunning musical achievement in its own right.

of Davis’ trumpet style had been glimpsed in several earlier recordings (including the Evans-arranged version of “My Ship” on “Miles Ahead“), and it was the focus of the Davis/Evans collaboration on “Porgy and Bess”. Like a great opera singer, Davis is at center stage, surrounded by Evans’ richly colored orchestrations. There is little that can prepare the listener for the screaming intensity of the trumpets on the opening track, “Buzzard Song”, or the sheer power at the climax of “My Man’s Gone Now”. And while Evans has jettisoned Gershwin’s original orchestrations and tune sequence, he has created splendid original music of his own, including the jaunty tuba/bass line on “Buzzard”, the nearly-iconic counter melody on “Summertime” and the fast, straight-ahead variant on the funeral theme “Gone”. And could anyone but Miles Davis offer such a wide range of emotions without uttering a single word? He makes these songs personal, and that engages us as listeners. There are many other wonders to this recording: Evans’ acute dramatic sense (notice that the climax of “My Man’s Gone Now” is only a few bars, but its effect carries on much longer), Davis’ unique approach to modal improvisation (still a new concept in jazz at the time), and the glimpses of other “Porgy” arias inserted into the improvisations and arrangements (The notes mention the interpolation of “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’” at the beginning of “It Ain’t Necessarily So”, but I doubt that many recognize “They Pass By Singin’” as the intro to “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” or the reprise of the “Gone” motive near the end of “Boat”). An album that truly rewards repeated listening, the Davis/Evans version of “Porgy and Bess” is a brilliant transformation of Gershwin’s score, and a stunning musical achievement in its own right.

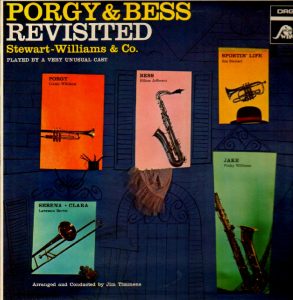

An interesting variation on the instrumentalist-as-character theme comes in the 1959 Warner Brothers LP, “Porgy and Bess Revisited”. Backed by arrangements by Jim Timmens, the main characters of the opera are played by a cast of Ellington alumni, who portray their characters through their unique instrumental voices. The majestic trumpet of Cootie Williams brings strength to the character of Porgy, and the tender warmth of Hilton Jefferson’s alto sax enriches his portrayal of Bess. The impish half-valve and muted effects of cornetist Rex Stewart makes him a natural as Sportin’ Life, and Lawrence Brown brings his smooth trombone style to the dual roles of Clara and Serena. The only non-Ellingtonian soloist was baritone saxophonist Pinky Williams, whose rough-hewed style was perfect for the fisherman Jake. Timmens is virtually forgotten today, but during this period, he created similar jazz treatments of Gilbert and Sullivan, and Jerome Kern’s “Show Boat”. His arranging style is quite uneven, with some settings offering fresh, re-imagined versions of the originals, while others seem unduly syrupy or needlessly hyperactive. Still, it is the soloists that make this album a success, and Stewart, Brown, and Cootie Williams are in spectacular form. The album was reissued by DRG Swing in the early 80s, and sealed copies of that vinyl edition can still be purchased online.

An interesting variation on the instrumentalist-as-character theme comes in the 1959 Warner Brothers LP, “Porgy and Bess Revisited”. Backed by arrangements by Jim Timmens, the main characters of the opera are played by a cast of Ellington alumni, who portray their characters through their unique instrumental voices. The majestic trumpet of Cootie Williams brings strength to the character of Porgy, and the tender warmth of Hilton Jefferson’s alto sax enriches his portrayal of Bess. The impish half-valve and muted effects of cornetist Rex Stewart makes him a natural as Sportin’ Life, and Lawrence Brown brings his smooth trombone style to the dual roles of Clara and Serena. The only non-Ellingtonian soloist was baritone saxophonist Pinky Williams, whose rough-hewed style was perfect for the fisherman Jake. Timmens is virtually forgotten today, but during this period, he created similar jazz treatments of Gilbert and Sullivan, and Jerome Kern’s “Show Boat”. His arranging style is quite uneven, with some settings offering fresh, re-imagined versions of the originals, while others seem unduly syrupy or needlessly hyperactive. Still, it is the soloists that make this album a success, and Stewart, Brown, and Cootie Williams are in spectacular form. The album was reissued by DRG Swing in the early 80s, and sealed copies of that vinyl edition can still be purchased online.

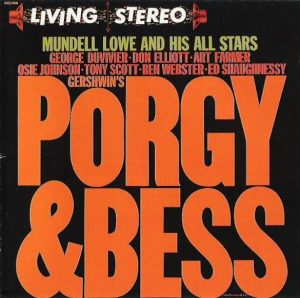

Most actors will admit that they can’t order from a menu without a script; on the other hand, most jazz musicians are best at playing themselves, While several of the albums discussed in this essay demanded a certain degree of dramatic aptitude, the rest of the recordings used the music from “Porgy and Bess” as vehicles for improvisation, with no characterization provided or implied. In 1958, Mundell Lowe recorded 10 songs from the score for an album on RCA’s  budget label, Camden. Seven of the tracks used a septet featuring Art Farmer (trumpet), Don Elliott (mellophone and vibes), Ben Webster (tenor sax), Tony Scott (clarinet and bari sax), Lowe (guitar), George Duvivier (bass) and Osie Johnson (drums). The remaining tracks feature the rhythm section, with Ed Shaughnessy replacing Johnson and doubling on vibes. All of the tracks are heavily arranged with tight block chords for the horns, and minimal solo space. The stiff arrangement on “I Loves You, Porgy” nearly stifles the trio’s creativity, but the chart on “A Long Pull to Get There” has an attractive loose rhythm and a welcome reprieve from the block chord horn voicings. Scott takes all of his solos on bari, featuring a gruffer sound that expected, and when Webster takes over for him on “Summertime”, the tenor man is warm and tender (Webster’s gruff side comes in later). After Webster, Farmer—who doesn’t get nearly enough solo space on the album—offers a beautifully nuanced variation. Elliott is featured on both of his instruments, with a fine ensemble lead and mellophone solo on “My Man’s Gone Now” and a swinging vibes solo on “A Red-Headed Woman”. Lowe improvises a marvelous block-chord solo on “Oh, Bess, Where’s My Bess” and imbues “It Ain’t Necessarily So” with bluesy bent notes. Throughout the album, he shows why he was considered one of the tastiest guitarists of his time. Although it is a modest effort, Lowe’s version of “Porgy and Bess” is pleasant and swinging, if not terribly challenging.

budget label, Camden. Seven of the tracks used a septet featuring Art Farmer (trumpet), Don Elliott (mellophone and vibes), Ben Webster (tenor sax), Tony Scott (clarinet and bari sax), Lowe (guitar), George Duvivier (bass) and Osie Johnson (drums). The remaining tracks feature the rhythm section, with Ed Shaughnessy replacing Johnson and doubling on vibes. All of the tracks are heavily arranged with tight block chords for the horns, and minimal solo space. The stiff arrangement on “I Loves You, Porgy” nearly stifles the trio’s creativity, but the chart on “A Long Pull to Get There” has an attractive loose rhythm and a welcome reprieve from the block chord horn voicings. Scott takes all of his solos on bari, featuring a gruffer sound that expected, and when Webster takes over for him on “Summertime”, the tenor man is warm and tender (Webster’s gruff side comes in later). After Webster, Farmer—who doesn’t get nearly enough solo space on the album—offers a beautifully nuanced variation. Elliott is featured on both of his instruments, with a fine ensemble lead and mellophone solo on “My Man’s Gone Now” and a swinging vibes solo on “A Red-Headed Woman”. Lowe improvises a marvelous block-chord solo on “Oh, Bess, Where’s My Bess” and imbues “It Ain’t Necessarily So” with bluesy bent notes. Throughout the album, he shows why he was considered one of the tastiest guitarists of his time. Although it is a modest effort, Lowe’s version of “Porgy and Bess” is pleasant and swinging, if not terribly challenging.

One of the most beloved adaptations of the Gershwin score is “The Jazz Soul of Porgy and Bess”, a big band album arranged andconducted by Bill Potts. The album, recorded in January 1959, was a major breakthrough for Potts, who was best known for his charts for Washington, DC’s big band, THE Orchestra. Potts’ career was interrupted when he was injured in a serious auto accident, and the “Porgy and Bess” album marked his first recordings since his involuntary hiatus. Potts studied Gershwin’s score for six weeks, and then created his own arrangements, which took a further thirteen weeks. While some of Potts’ hard-swinging charts sound radically different than the originals, he did not abandon the original score entirely: throughout the album, he stealthily hints at parts of Gershwin’s incidental music, sometimes disguising the fragments as background riffs set in radically different tempos than Gershwin’s originals. Elsewhere, he transforms the opera into exciting big band jazz, as on the opening track, an intensely swinging (and nearly unrecognizable) “Summertime”. As the album progresses, the momentum never drops as the band thrillingly executes Potts’ powerful ensemble figures. The band is loaded with amazing soloists who bring this score to life: Al Cohn and Zoot Sims swing effortlessly through “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’”, Bill Evans and Art Farmer offer elegant interpretations of “I Loves You, Porgy”, Phil Woods projects the deep emotion of “Bess, You Is My Woman”, and Bob Brookmeyer and Charlie Shavers are superbly paired in “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess”. The album also offers fine solo examples of lesser-known musicians: trumpeter Marky Markowitzplays a glorious solo on “My Man’s Gone Now”, baritone saxophonist Sol Schlinger performs a sprightly improvisation in a medley of minor themes, and trombonists Earl Swope and Rod Levitt are featured on “A Woman Is a Sometime Thing” and “It Ain’t Necessarily So”, respectively. While Bill Potts was active as an arranger for many years, he never again reached the success that he achieved with this album.

One of the most beloved adaptations of the Gershwin score is “The Jazz Soul of Porgy and Bess”, a big band album arranged andconducted by Bill Potts. The album, recorded in January 1959, was a major breakthrough for Potts, who was best known for his charts for Washington, DC’s big band, THE Orchestra. Potts’ career was interrupted when he was injured in a serious auto accident, and the “Porgy and Bess” album marked his first recordings since his involuntary hiatus. Potts studied Gershwin’s score for six weeks, and then created his own arrangements, which took a further thirteen weeks. While some of Potts’ hard-swinging charts sound radically different than the originals, he did not abandon the original score entirely: throughout the album, he stealthily hints at parts of Gershwin’s incidental music, sometimes disguising the fragments as background riffs set in radically different tempos than Gershwin’s originals. Elsewhere, he transforms the opera into exciting big band jazz, as on the opening track, an intensely swinging (and nearly unrecognizable) “Summertime”. As the album progresses, the momentum never drops as the band thrillingly executes Potts’ powerful ensemble figures. The band is loaded with amazing soloists who bring this score to life: Al Cohn and Zoot Sims swing effortlessly through “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’”, Bill Evans and Art Farmer offer elegant interpretations of “I Loves You, Porgy”, Phil Woods projects the deep emotion of “Bess, You Is My Woman”, and Bob Brookmeyer and Charlie Shavers are superbly paired in “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess”. The album also offers fine solo examples of lesser-known musicians: trumpeter Marky Markowitzplays a glorious solo on “My Man’s Gone Now”, baritone saxophonist Sol Schlinger performs a sprightly improvisation in a medley of minor themes, and trombonists Earl Swope and Rod Levitt are featured on “A Woman Is a Sometime Thing” and “It Ain’t Necessarily So”, respectively. While Bill Potts was active as an arranger for many years, he never again reached the success that he achieved with this album.

There are only a few instrumental versions of “Porgy and Bess” for rhythm section alone. In 1959, Hank Jones recorded a version for Capitol with Kenny Burrell, Milt Hinton and Elvin Jones. The arrangements were written by Al  Cohn. Unfortunately, all of the tunes were very short, and many of the solos were little more than melodic paraphrases. However, the Jones album may be the only place to hear jazz versions of the picnic music “I Ain’t Got No Shame” and “Oh, I Can’t Sit Down”. The Oscar Peterson Trio’s version was part of a series of albums devoted to Broadway shows, and it was recorded in a single day in October 1959. The team of Peterson, Ray Brown and Ed Thigpen had only been together for about a year, but the group was already amazing audiences and musicians with their tight rhythmic feel and extraordinary non-verbal communication. It sounds like the

Cohn. Unfortunately, all of the tunes were very short, and many of the solos were little more than melodic paraphrases. However, the Jones album may be the only place to hear jazz versions of the picnic music “I Ain’t Got No Shame” and “Oh, I Can’t Sit Down”. The Oscar Peterson Trio’s version was part of a series of albums devoted to Broadway shows, and it was recorded in a single day in October 1959. The team of Peterson, Ray Brown and Ed Thigpen had only been together for about a year, but the group was already amazing audiences and musicians with their tight rhythmic feel and extraordinary non-verbal communication. It sounds like the  trio is playing loose arrangements, but they only use them as guides for balanced performances, not for structured ensemble passages. For the most part, Peterson keeps his prodigious technique in check, allowing Brown to create lovely counter melodies to the pianist’s improvisations (especially on “I Loves You, Porgy”). Thigpen gets fewer opportunities, but he is tremendously effective on “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leaving Soon for New York”, where he kicks the band along between Peterson’s lines. On medium- and up-tempo pieces like “Summertime”, ‘It Ain’t Necessarily So”, and “Oh Lawd, I’m On My Way”, the trio creates unshakeable grooves that are hard to resist. Peterson also includes two of the street vendor calls, “Here Comes De Honey Man” and “Strawberry Woman” in short but effective arrangements. Both “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess” and “Bess, You Is My Woman” open and close with unaccompanied piano solos, and each displays Peterson’s subtle touch and refined sense of rubato.

trio is playing loose arrangements, but they only use them as guides for balanced performances, not for structured ensemble passages. For the most part, Peterson keeps his prodigious technique in check, allowing Brown to create lovely counter melodies to the pianist’s improvisations (especially on “I Loves You, Porgy”). Thigpen gets fewer opportunities, but he is tremendously effective on “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leaving Soon for New York”, where he kicks the band along between Peterson’s lines. On medium- and up-tempo pieces like “Summertime”, ‘It Ain’t Necessarily So”, and “Oh Lawd, I’m On My Way”, the trio creates unshakeable grooves that are hard to resist. Peterson also includes two of the street vendor calls, “Here Comes De Honey Man” and “Strawberry Woman” in short but effective arrangements. Both “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess” and “Bess, You Is My Woman” open and close with unaccompanied piano solos, and each displays Peterson’s subtle touch and refined sense of rubato.

Peterson returned to the Gershwin score seventeen years later for a duet album with Joe Pass. Playing a clavichord (an 18th century keyboard  instrument), Peterson brings a fragile quality to the music. Pass plays acoustic guitar and the similar sounds of the two instruments enhances the music’s intimacy. At times, the music sounds like it was lifted from another era, but elsewhere, the pairing sounds at home within a jazz setting. “Bess, You Is My Woman” becomes the most delicate of duets here, while “It Ain’t Necessarily So” becomes a sassy strut that could have been played on the duo’s modern instruments (In fact, it might have been better that way: like most ancient keyboard instruments, clavichords don’t respond well to fast fingers and heavy hands, and at several points on the album, the instrument sounds like it’s going out of tune). Because the clavichord is a relatively quiet instrument, Pass’ guitar becomes an equal partner with the keyboard, and it is noteworthy that there are two solo guitar tracks but no solo clavichord performances. Both of Pass’ solo pieces, “My Man’s Gone Now” and “They Pass by Singin’”, deal with different aspects of loneliness, and Pass barely improvises on either, letting Gershwin’s melodies tell the stories. As on his earlier version, Peterson starts “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess” with a slow unaccompanied solo, but here the mood lightens when Pass enters with a brisk jazz waltz background. The closing track, “Strawberry Woman” undergoes the greatest changes. Peterson and Pass take this tiny piece of original music and expand it into a nearly six minute performance, exploiting the bluesy nature of its melody and harmony. With its sound dominated by plucked strings, the piece sounds like a modern version of the Lonnie Johnson/Eddie Lang guitar duets, and that is a compliment to all four musicians.

instrument), Peterson brings a fragile quality to the music. Pass plays acoustic guitar and the similar sounds of the two instruments enhances the music’s intimacy. At times, the music sounds like it was lifted from another era, but elsewhere, the pairing sounds at home within a jazz setting. “Bess, You Is My Woman” becomes the most delicate of duets here, while “It Ain’t Necessarily So” becomes a sassy strut that could have been played on the duo’s modern instruments (In fact, it might have been better that way: like most ancient keyboard instruments, clavichords don’t respond well to fast fingers and heavy hands, and at several points on the album, the instrument sounds like it’s going out of tune). Because the clavichord is a relatively quiet instrument, Pass’ guitar becomes an equal partner with the keyboard, and it is noteworthy that there are two solo guitar tracks but no solo clavichord performances. Both of Pass’ solo pieces, “My Man’s Gone Now” and “They Pass by Singin’”, deal with different aspects of loneliness, and Pass barely improvises on either, letting Gershwin’s melodies tell the stories. As on his earlier version, Peterson starts “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess” with a slow unaccompanied solo, but here the mood lightens when Pass enters with a brisk jazz waltz background. The closing track, “Strawberry Woman” undergoes the greatest changes. Peterson and Pass take this tiny piece of original music and expand it into a nearly six minute performance, exploiting the bluesy nature of its melody and harmony. With its sound dominated by plucked strings, the piece sounds like a modern version of the Lonnie Johnson/Eddie Lang guitar duets, and that is a compliment to all four musicians.

The Modern Jazz Quartet’s version of “Porgy and Bess” was released in 1965, in time to commemorate the opera’s 30th anniversary. While most album versions contained 10-12 songs from the opera, John Lewis chose only seven pieces, which allowed time for more elaborate settings (Like Gil Evans and Bill Potts, Lewis also included melodic fragments from the opera as introductions to longer works). “Summertime” became one of the MJQ’s most requested concert numbers, but the album’s finest arrangement is “My Man’s Gone Now”. Starting with Percy Heath’s double-stops, Connie Kay’s precise finger cymbals and Lewis’ dramatic piano lines, the group ebbs and flows under Milt Jackson’s expressive theme statement and improvisation. The level of each crescendo builds successively, and then the tempo pushes forward as the group approaches the emotionally overwhelming climax. Then, to bring everything down before the recapitulation, Lewis plays a brief unaccompanied solo. Lewis’ setting of “It Ain’t Necessarily So” fragments the theme against frequently changing tempos and meters, and Kay’s drum improvisation. The tempo changes are very precise (and Lewis avoids writing similar sections in the same tempo). It is a testament to this wonderful ensemble that they lock into new grooves instantaneously, even when they only last for a few measures. The tempo is also quite flexible in “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess” as the group plays in a kind of controlled rubato. “Bess, You Is My Woman”, “I Loves You, Porgy”, “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York” and the aforementioned “Summertime” balance the program with straight-forward arrangements and more inspired solos.

The Modern Jazz Quartet’s version of “Porgy and Bess” was released in 1965, in time to commemorate the opera’s 30th anniversary. While most album versions contained 10-12 songs from the opera, John Lewis chose only seven pieces, which allowed time for more elaborate settings (Like Gil Evans and Bill Potts, Lewis also included melodic fragments from the opera as introductions to longer works). “Summertime” became one of the MJQ’s most requested concert numbers, but the album’s finest arrangement is “My Man’s Gone Now”. Starting with Percy Heath’s double-stops, Connie Kay’s precise finger cymbals and Lewis’ dramatic piano lines, the group ebbs and flows under Milt Jackson’s expressive theme statement and improvisation. The level of each crescendo builds successively, and then the tempo pushes forward as the group approaches the emotionally overwhelming climax. Then, to bring everything down before the recapitulation, Lewis plays a brief unaccompanied solo. Lewis’ setting of “It Ain’t Necessarily So” fragments the theme against frequently changing tempos and meters, and Kay’s drum improvisation. The tempo changes are very precise (and Lewis avoids writing similar sections in the same tempo). It is a testament to this wonderful ensemble that they lock into new grooves instantaneously, even when they only last for a few measures. The tempo is also quite flexible in “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess” as the group plays in a kind of controlled rubato. “Bess, You Is My Woman”, “I Loves You, Porgy”, “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York” and the aforementioned “Summertime” balance the program with straight-forward arrangements and more inspired solos.

In 1976, the Houston Grand Opera staged a new production of “Porgy and Bess”, including much of the music cut before the New York premiere. It was the first time an American opera company had performed the work, and the production led to a general re-appraisal of the original opera. RCA obtained the rights to record the production for its Red Seal label, and around the same time, Norman Granz produced a new jazz recording of the work for RCA  Victor. Ray Charles was selected to play Porgy. Charles lobbied to have Gladys Knight play Bess, but Granz wanted Cleo Laine for her extraordinary vocal range and her experience as an actress. Granz eventually won out, but that was far from the end of the problems for this recording. Reportedly, Charles was unprepared when he came to the studio, and at times, Laine sounds as if she’s coming off a cold. The duo recorded for four days in April with a large all-star orchestra arranged and conducted by Frank DeVol. Seventeen songs were recorded, but when Granz tallied the timings, there was only 62 minutes of music—too long for a single LP, and too short for two. He padded the album by bringing Charles and his rhythm section back into the studio to record instrumental versions of the songs recorded earlier. On the 2-LP set, the instrumental versions appeared next to the vocal renditions, which slowed the pace of the album. With the padding, the LPs ran 82 minutes, so much of the padding was removed when RCA reissued the album on CD.

Victor. Ray Charles was selected to play Porgy. Charles lobbied to have Gladys Knight play Bess, but Granz wanted Cleo Laine for her extraordinary vocal range and her experience as an actress. Granz eventually won out, but that was far from the end of the problems for this recording. Reportedly, Charles was unprepared when he came to the studio, and at times, Laine sounds as if she’s coming off a cold. The duo recorded for four days in April with a large all-star orchestra arranged and conducted by Frank DeVol. Seventeen songs were recorded, but when Granz tallied the timings, there was only 62 minutes of music—too long for a single LP, and too short for two. He padded the album by bringing Charles and his rhythm section back into the studio to record instrumental versions of the songs recorded earlier. On the 2-LP set, the instrumental versions appeared next to the vocal renditions, which slowed the pace of the album. With the padding, the LPs ran 82 minutes, so much of the padding was removed when RCA reissued the album on CD.

For all of the problems in its production, the finished album is quite good, especially when the instrumental versions are omitted. As in the other duo-vocalist versions discussed above, each singer sings the solos of their own gender, with occasional exceptions (Laine sings Porgy’s “They Pass By Singin’” and several solo pieces, including “Summertime” and “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’” became duets). Charles made his career by transforming other people’s music into his own sound, and he does that brilliantly here. His immense vocabulary of swoops, hollers and other melodic variations enliven tracks like “A Woman Is a Sometime Thing”, “Buzzard Song” and “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York”. Laine uses her musical and theatrical background to create interpretations that are intense (“My Man’s Gone Now”), reverent (“Oh Doctor Jesus”), romantic (“I Loves You, Porgy”) and saucy (“It Ain’t Necessarily So”). When Charles and Laine sing together, the chemistry works more times than not, and DeVol’s arrangements are also quite good overall. The set also includes a fine extended liner essay by British critic Benny Green, which includes copious information on the opera and its various adaptations, but also includes enough strong opinions to alienate most readers!

During the 1990s, Joe Henderson recorded several concept albums for Verve, including a 1997 collection of “Porgy and Bess” themes. The album maintains the song sequence from the opera (even grouping the songs by operatic act), and the liner notes are limited to the opera’s synopsis. Yet, there is no apparent instrumental characterization here, just a well-planned adaptation of the show’s highlights. Henderson’s arrangements use an all-star septet, but he rarely uses the entire group at once, even excluding his own tenor on a couple selections. The opening “Jasbo Brown’s Blues” sets the atmosphere, both in the traditional-sounding voicings and in the startling sound of John Scofield’s wailing electric guitar. “Summertime” features a subdued Chaka Khan on the vocal, and a restless broken rhythm pattern set up by Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette. Henderson balances the melody and progressive ideas in his solo, and Scofield’s improvisation breaks up the time against the rhythm section. Brief versions of “Here Comes de Honey Man” and “They Pass By Singin’” are played by trio (Henderson, Scofield and Stefon Harris) and duet (Conrad Herwig and Harris) respectively, before the instrumentalists (all those listed above, plus Tommy Flanagan) play a medium-tempo version of “My Man’s Gone Now” that bubbles with growing intensity, and a briskly grooving take on “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’”. Flanagan essays the theme of “Bess, You Is My Woman” unaccompanied, with Henderson joining in after the bridge. Their understated duet is one of the highlights of the disc. I’m less impressed with Sting’s vocal on “It Ain’t Necessarily So” which is so tied to the beat that the lyric’s meaning is diminished (somehow, he misses the humor in the line about Pharaoh’s daughter finding Moses—she said—in a stream). “I Loves You, Porgy” starts with Henderson’s tenor and Scofield’s acoustic guitar alone, before the rest of the rhythm section slides in underneath. It is the closest thing to a standard jazz ballad on this album, and it is quite effective, despite its brevity. Holland’s tiptoeing bass and DeJohnette’s quietly cooking drums enliven “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York”, and a jazz waltz version of “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess” concludes the album. Henderson is still underappreciated as an arranger, but his subtly unified settings of the “Porgy and Bess” music shows another way to retain the mood of a great work without copying the original settings.

During the 1990s, Joe Henderson recorded several concept albums for Verve, including a 1997 collection of “Porgy and Bess” themes. The album maintains the song sequence from the opera (even grouping the songs by operatic act), and the liner notes are limited to the opera’s synopsis. Yet, there is no apparent instrumental characterization here, just a well-planned adaptation of the show’s highlights. Henderson’s arrangements use an all-star septet, but he rarely uses the entire group at once, even excluding his own tenor on a couple selections. The opening “Jasbo Brown’s Blues” sets the atmosphere, both in the traditional-sounding voicings and in the startling sound of John Scofield’s wailing electric guitar. “Summertime” features a subdued Chaka Khan on the vocal, and a restless broken rhythm pattern set up by Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette. Henderson balances the melody and progressive ideas in his solo, and Scofield’s improvisation breaks up the time against the rhythm section. Brief versions of “Here Comes de Honey Man” and “They Pass By Singin’” are played by trio (Henderson, Scofield and Stefon Harris) and duet (Conrad Herwig and Harris) respectively, before the instrumentalists (all those listed above, plus Tommy Flanagan) play a medium-tempo version of “My Man’s Gone Now” that bubbles with growing intensity, and a briskly grooving take on “I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’”. Flanagan essays the theme of “Bess, You Is My Woman” unaccompanied, with Henderson joining in after the bridge. Their understated duet is one of the highlights of the disc. I’m less impressed with Sting’s vocal on “It Ain’t Necessarily So” which is so tied to the beat that the lyric’s meaning is diminished (somehow, he misses the humor in the line about Pharaoh’s daughter finding Moses—she said—in a stream). “I Loves You, Porgy” starts with Henderson’s tenor and Scofield’s acoustic guitar alone, before the rest of the rhythm section slides in underneath. It is the closest thing to a standard jazz ballad on this album, and it is quite effective, despite its brevity. Holland’s tiptoeing bass and DeJohnette’s quietly cooking drums enliven “There’s A Boat Dat’s Leavin’ Soon for New York”, and a jazz waltz version of “Oh Bess, Where’s My Bess” concludes the album. Henderson is still underappreciated as an arranger, but his subtly unified settings of the “Porgy and Bess” music shows another way to retain the mood of a great work without copying the original settings.

The most recent adaptation of the Gershwin score is titled “A Different Porgy and Another Bess”, and it features vocals by French-Belgian David Linx and Portuguese Maria João backed by the Brussels Jazz Orchestra. As its title implies, the album veers from Gershwin’s score in several ways. For example, the album opens with “A Red-Headed Woman”(!) arranged by trombonist Lode Mertens, who discovers several new avenues for this simple song, including an intriguing mixed-meter feel, vocal duets with new lyrics by Linx, an intense solo passage for alto saxophonist Dieter Limbourg, and a warmly-scored chorus for the brass. Each track was scored by a different arranger, so there are several different and unexpected approaches to the music. However, a prevalence of triple-time settings and a common language of instrumental voicings unify the album. The Brussels Jazz Orchestra plays with precision, emotion and swing, which should cause most Americans to reevaluate their prejudices about European big bands. The individual soloists are also very impressive, including Hendrik Braeckman (guitar), Nathalie Loriers (piano), Kurt van Herck and Bart Defoort (tenor sax), Pierre Drevet (trumpet) and the aforementioned Mertens and Limbourg. The vocalists may not be native English speakers, but their control of the language is exemplary, and their portrayals of the characters are quite convincing. Both scat well and they have excellent command of the jazz style. Linx’ voice gets a little strident at times, and João’s little-girl voice and throbbing vibrato is rather cloying, but their voices blend well when they sing together.

The most recent adaptation of the Gershwin score is titled “A Different Porgy and Another Bess”, and it features vocals by French-Belgian David Linx and Portuguese Maria João backed by the Brussels Jazz Orchestra. As its title implies, the album veers from Gershwin’s score in several ways. For example, the album opens with “A Red-Headed Woman”(!) arranged by trombonist Lode Mertens, who discovers several new avenues for this simple song, including an intriguing mixed-meter feel, vocal duets with new lyrics by Linx, an intense solo passage for alto saxophonist Dieter Limbourg, and a warmly-scored chorus for the brass. Each track was scored by a different arranger, so there are several different and unexpected approaches to the music. However, a prevalence of triple-time settings and a common language of instrumental voicings unify the album. The Brussels Jazz Orchestra plays with precision, emotion and swing, which should cause most Americans to reevaluate their prejudices about European big bands. The individual soloists are also very impressive, including Hendrik Braeckman (guitar), Nathalie Loriers (piano), Kurt van Herck and Bart Defoort (tenor sax), Pierre Drevet (trumpet) and the aforementioned Mertens and Limbourg. The vocalists may not be native English speakers, but their control of the language is exemplary, and their portrayals of the characters are quite convincing. Both scat well and they have excellent command of the jazz style. Linx’ voice gets a little strident at times, and João’s little-girl voice and throbbing vibrato is rather cloying, but their voices blend well when they sing together.

However, I must object to the politically correct language on the Brussels recording. We are subjected to titles and lyrics that the Gershwins never wrote, such as “I’ve Got Plenty of Nothing”, “Bess, You Are My Woman” and “I Love You Porgy” (They don’t include “It Ain’t Necessarily So”; would it have become—in Benny Green’s prophetic 1976 quip—“It Is Not Necessarily Thus”?). Even the new Broadway production, which claims to bring Gershwin’s work up to date, retains most of the original dialect. After all, the Gershwins composed the deliciously ungrammatical “I Got Rhythm”, and they could have easily set “Porgy and Bess” in American English. Instead, they tried to capture the feeling of the Gullah dialect, and George deliberately set his recitatives to the Gullah speech rhythms. While there are several moments in the opera that are stereotypical and pandering, the Gershwins and the Heywards present a loving view of a poorly educated, but well-adjusted community. Opera is a far different form than documentaries, but the listener gets a better view of the Gullah people through “Porgy and Bess” than they would of the Japanese from “The Mikado” or the gypsies through “Carmen”. While both the current Broadway production and the Brussels Jazz Orchestra recording have several fine moments, I doubt that either will stand up to future audiences as well as George Gershwin’s original masterpiece.