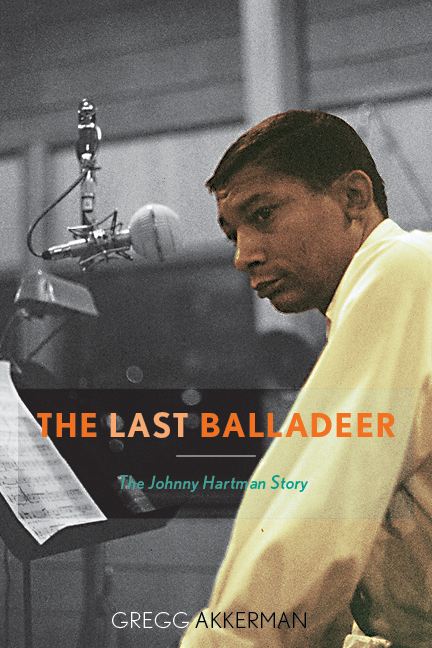

Around 2009, when Gregg Akkerman attempted to research the life and music of Johnny Hartman, he found that there were no books on the perpetually underrated vocalist.. Upon further research, he discovered why: There was a plethora of misinformation on the singer, from his birth date to the circumstances behind his famous collaboration with John Coltrane, and some of that misinformation came directly from the singer himself. Further, there were all kinds of scurrilous stories about bad habits that Hartman never had, and tours he never made. Akkerman has sorted through all of this rubble to create a near-definitive Hartman biography, “The Last Balladeer”. The amount of original research is astounding, as Akkerman interviewed musicians, family members and music business insiders to fill in the historical gaps of Hartman’s checkered career. He also listened to hours of rare and unreleased recordings of Hartman in concert and studio settings. In many cases, these performances were only known to the public through newspaper and magazine reviews, and Akkerman’s research allows him to reassess the music for himself and for us. His concise writing keeps the story moving and holds the reader’s interest throughout.

Around 2009, when Gregg Akkerman attempted to research the life and music of Johnny Hartman, he found that there were no books on the perpetually underrated vocalist.. Upon further research, he discovered why: There was a plethora of misinformation on the singer, from his birth date to the circumstances behind his famous collaboration with John Coltrane, and some of that misinformation came directly from the singer himself. Further, there were all kinds of scurrilous stories about bad habits that Hartman never had, and tours he never made. Akkerman has sorted through all of this rubble to create a near-definitive Hartman biography, “The Last Balladeer”. The amount of original research is astounding, as Akkerman interviewed musicians, family members and music business insiders to fill in the historical gaps of Hartman’s checkered career. He also listened to hours of rare and unreleased recordings of Hartman in concert and studio settings. In many cases, these performances were only known to the public through newspaper and magazine reviews, and Akkerman’s research allows him to reassess the music for himself and for us. His concise writing keeps the story moving and holds the reader’s interest throughout.

Without a doubt, the 1963 Impulse album “John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman” was the singer’s greatest achievement. It brought him more financial and artistic success than any of his other recordings, and it remains one of the greatest vocal jazz albums ever made. Akkerman devotes well over a chapter to this album, and it is here that he presents his best piece of research: The album was not a collection of first takes as Hartman claimed. In two instances, the final tracks combined music from different takes, and there are alternate takes and rehearsal recordings of each title. Further, Coltrane dubbed in his saxophone solos at a later date, and an early pressing of the album left out Coltrane’s part by mistake. The full session reels were presumed lost, but a few years ago, someone tried to auction them off on eBay. The Coltrane family intervened before the auction commenced. Universal Music—who theoretically own anything recorded for Impulse— and the Coltranes—who now possess the tapes—have been wrangling about this music ever since, and we can only hope that the publication of Akkerman’s book will bring resolution between the parties and the eventual release of this important music.

Akkerman is a professional musician and educator, and his book offers superb verbal descriptions of Hartman’s recordings and concert performances. These word-paintings are a valuable part of any musical biography, for they encourage the reader to explore the music. Thus, it is rather surprising to not find a detailed discussion of the Coltrane/Hartman record in this book. Perhaps Akkerman assumed that his audience would already know this classic album, and would not require a detailed description. Yet, his book is precisely the place for an in-depth assessment of this recording, if for no other reason than to discuss the elements—great and small—that make this album such a classic.

One of the lingering questions about Hartman is whether he was a jazz singer or a pop singer. Akkerman spends a lot of time discussing this issue without drawing any real conclusions. In truth, defining a jazz singer is as difficult as defining jazz itself. Like most of his peers, Hartman straddled the fence, finding an audience that appreciated both classic pop and straight-ahead jazz. Hartman’s audience was never as big as it could have been, and it’s anyone’s guess why. Some of Akkerman’s theories for this are quite plausible, but we may never know all of the reasons. Yet, with its bountiful research, “The Last Balladeer” paints a full-color portrait of a singer we only knew through pencil sketches.