For Bill Evans, 1968 must have been a very trying year. Since emerging on the jazz scene in the mid-1950s, Evans was known for his passion for beauty; now the world around him was turning very ugly. There was literally no way to miss it. The Vietnam War appeared in all its horrors on the evening news, and the Tet offensive in late January had reinforced the power of the enemy Viet Cong. In a nationally broadcast television special, Walter Cronkite concluded that the Vietnam War could not be won by conventional means. These remarks by Cronkite, known as “the most trusted man in America”, helped convince Lyndon B. Johnson not to seek a second term as US President. While LBJ was not idle during his final year in office, he was essentially a lame-duck president when the country most needed his guidance. Robert F. Kennedy entered the presidential race shortly after Johnson’s announcement, running on a platform of non-aggressive foreign policy and social justice, but after winning the California Democratic primary in June, he was gunned down in the kitchen of Los Angeles’ Ambassador Hotel. Two months later, chaos would reign at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Two months before Kennedy’s murder, civil rights leader Martin Luther King was assassinated outside a motel room in Memphis. King’s death sparked riots throughout the country, with 46 people dead in the aftermath. On the global front, students and workers essentially shut down the city of Paris in May through a combination of protests and strikes. The hope of democracy in Eastern Europe ended when Soviet tanks plowed through the capital of Czechoslovakia, thus crushing the “Prague Spring”. In music, jazz’s dwindling audience was divided by the increasingly dissonant sounds of free jazz, and the gigantic influence of rock music, which was moving from pop-oriented songs into complex album-oriented styles.

Despite all of these concurrent events, Evans was still able to create lyrical masterpieces alone and with his trio. Yet at the same time, he seemed willing to let the ensemble sound evolve in new ways. When drummer Arnold Wise left the trio in the early months of 1968, Evans’ bassist Eddie Gomez suggested Jack DeJohnette as a replacement. DeJohnette started out as a pianist in Chicago, but was best known at the time as the powerful drummer in Charles Lloyd’s quartet. In truth, DeJohnette had always been a sensitive player—just listen to him on Lloyd’s album “Forest Flower” for abundant examples—but his brief tenure in the Evans trio gave him plenty of opportunities to express himself at reduced volume. The surviving recordings of the Evans trio show that DeJohnette could work wonders with brushes, but he could also provide active, explosive commentary rarely matched by any of Evans’ previous or consequent drummers.

It is not entirely clear how long DeJohnette remained in the Evans trio. Wise was still playing with the group during an engagement at the Village Vanguard in early February. In an interview conducted in London during the following summer, Evans told Les Tomkins that the trio with DeJohnette had played three television shows and a two-week engagement at the Top of the Gate (located above the Village Gate club in New York) before traveling to Europe. While on the Continent, they performed at the Montreux Jazz Festival, recorded a studio album in Villigen, West Germany, did a radio broadcast in Holland, and then played a month-long residency at Ronnie Scott’s in London. The trio was back in New York by mid-August where they played another gig at the Vanguard. The trio returned to the Vanguard in mid-September but with John Dentz at the drums. Five weeks later, when the trio returned to the Top of the Gate, DeJohnette’s permanent replacement, Marty Morell was in place. DeJohnette left Evans to join Miles Davis, replacing Tony Williams who had left to start his group, Lifetime. Davis reportedly heard the Evans trio at Ronnie Scott’s, but DeJohnette states that Davis only offered a job to bassist Dave Holland, who played in a group that alternated sets with the Evans trio (Interestingly, another future Davis sideman also played in that band: guitarist John McLaughlin!) DeJohnette says that he had already subbed for Williams in Davis’ group, and therefore had no need to audition for the trumpeter.

Apparently, DeJohnette’s first recordings with the Evans trio were the three TV appearances, all of which were hosted by “the jazz priest” Father Norman J. O’Connor, produced by Ethel Burns, and aired on New York City’s WCBS. Two of the shows were episodes of O’Connor’s series, “Dial M for Music”, a program designed to encourage young adults to explore jazz. The earliest of these episodes contrasted the piano styles of Evans and Teddy Wilson. No video or audio recordings of this show were available for review, but Evans’ biographer Peter Pettinger states that Evans improvised over two pre-recorded lines on “Emily” to illustrate the overdubbing technique used on Evans’ LP, “Conversations with Myself”. Internet discographer Ehsan Khoshbakht adds that the trio performed “Who Can I Turn To?” Ironically, while both Pettinger and Khoshbakht confirm DeJohnette’s presence on this recording—and it is not known whether they watched a video or listened the audio alone—the drummer has no memory of making this show! On another episode (which aired in July while the Evans trio was still in London) the trio played an electrifying version of “Stella by Starlight” where DeJohnette’s invigorating brush work inspired a finger-busting Gomez solo; when DeJohnette changed to sticks, Evans dug deep into the keyboard, engaging in sublime rhythmic counterpoint with his new drummer. DeJohnette’s stick work also enlivens the second half—basically the jazz section—of a collaboration with the CBS Orchestra on “Granados”. Finally, just before leaving for Montreux, the Evans trio appeared on a remarkable (and extremely rare) live broadcast called “Robert F. Kennedy: A Contemporary Memorial”. This show, which aired just three days after RFK’s assassination, featured a plethora of jazz legends—more details can be found here—with Evans’ trio offering an understated rendition of “Time Remembered”. Here, DeJohnette played brushes throughout but provided intriguing cross-rhythms against Evans and Gomez.

The energy only hinted at during the TV shows is further developed within the trio’s first LP, “Bill Evans at the Montreux Jazz Festival” (Verve 827 844). The trio opens with “One for Helen”, an Evans composition dedicated to his manager Helen Keane. The piece is a rhythmic obstacle course where the ground beat is hard to discern. The trio accentuates the rhythmic play by steering away from the strong beats while throwing ideas from one side of the bandstand to the other. Evans’ arrangement of Harold Arlen’s “A Sleepin’ Bee” trades the song’s peaceful reverie for a dynamic re-structuring of the song’s pulse. While DeJohnette keeps a straight tempo on the ride cymbal, he uses the rest of the drum set to take part in the intense counterpoint initiated by Evans and Gomez. Earl Zindars’ “Mother of Earl” is a calming piece, and DeJohnette’s exquisite brush work anticipates and comments upon the twists and turns of Evans’ improvisation, and his delicate strokes of the cymbals are simply breathtaking. Gomez’s bass seems to be everywhere at the same time; his solo and accompaniment style is much flashier here than in later years, but his busy playing is quite at home with the high level of musical conversation within this trio. “Nardis” is DeJohnette’s feature, but before he solos, he plays brilliant accompaniments to Gomez and Evans as he follows the intricate contours of each solo and discovers the right sounds to comment (and occasionally goad) his fellow soloists. DeJohnette’s own solo displays a masterful sense of dynamics and impressive use of the various pitches within his drum kit.

The energy only hinted at during the TV shows is further developed within the trio’s first LP, “Bill Evans at the Montreux Jazz Festival” (Verve 827 844). The trio opens with “One for Helen”, an Evans composition dedicated to his manager Helen Keane. The piece is a rhythmic obstacle course where the ground beat is hard to discern. The trio accentuates the rhythmic play by steering away from the strong beats while throwing ideas from one side of the bandstand to the other. Evans’ arrangement of Harold Arlen’s “A Sleepin’ Bee” trades the song’s peaceful reverie for a dynamic re-structuring of the song’s pulse. While DeJohnette keeps a straight tempo on the ride cymbal, he uses the rest of the drum set to take part in the intense counterpoint initiated by Evans and Gomez. Earl Zindars’ “Mother of Earl” is a calming piece, and DeJohnette’s exquisite brush work anticipates and comments upon the twists and turns of Evans’ improvisation, and his delicate strokes of the cymbals are simply breathtaking. Gomez’s bass seems to be everywhere at the same time; his solo and accompaniment style is much flashier here than in later years, but his busy playing is quite at home with the high level of musical conversation within this trio. “Nardis” is DeJohnette’s feature, but before he solos, he plays brilliant accompaniments to Gomez and Evans as he follows the intricate contours of each solo and discovers the right sounds to comment (and occasionally goad) his fellow soloists. DeJohnette’s own solo displays a masterful sense of dynamics and impressive use of the various pitches within his drum kit.

Evans had recorded “I Loves You, Porgy” several times, but the Montreux version is a classic, featuring his splendid reharmonization and a wonderfully-controlled sense of rubato. The free tempo continues in the solo opening to another Evans favorite, “The Touch of Your Lips”. When the trio enters, Evans seems to push the rhythm from the keyboard, finding little resistance from Gomez (who flutters around the bass like a hip bumblebee) and DeJohnette (who creates a fine counterpoint with just brushes on snare and cymbals). Gomez’s feature on “Embraceable You” shows the bassist’s stunning dexterity. The arrangement jumps back and forth between two keys and two tempos, and as Pettinger notes, it is very difficult to discern how the group achieved the sudden tempo changes. “Someday My Prince Will Come” expands on the rhythmic maze of “One for Helen” by blurring the lines between triple and duple meter. At times, it sounds like both meters are being played simultaneously; still the group maintains a distinct groove that works within each time signature. Evans darts around the rhythm with remarkable improvised lines, while Gomez works against the beat in his solo. When Evans and DeJohnette trade four-bar exchanges, the meter is 4/4, but DeJohnette keeps the rhythmic ambiguity going with an ongoing triplet feeling on his cymbals. This may have been the last scheduled tune of the set, but the audience wouldn’t let the group leave without an encore or two. Evans jumps into another rhythmic showpiece, “Walkin’ Up” and the performance includes intense solos by all three principals played within three minutes and 20 seconds. The final piece is an elegant solo reading of Denny Zeitlin’s “Quiet Now”. Unissued until the CD era, it is an appropriate closer for this set. Bearing none of the rhythmic interplay of what came before, it offered the audience the peaceful side of Evans’ art—a side which did not surface much during this period.

Five days after the Montreux performance, the Evans trio travelled to Villigen, Germany in the Black Forest to record at the home studio of MPS Records owner, Hans Georg Brunner-Schwer. No satisfactory explanation has ever been given as to why this recording was made. Evans was under exclusive contract to Verve (and the hastily written MPS agreement states that the recordings would not be issued without the permission of Evans and/or Keane). Perhaps the enthusiasm of Brunner-Schwer caused everyone to proceed despite the legal obstacles. Or maybe Evans was eager to make a recording similar to the “Exclusively for my Friends” dates which Oscar Peterson had recorded in the MPS studio. Whatever the reason, the Evans trio recorded 94 minutes of music on June 20. At some point, Brunner-Schwer sequenced an LP and assigned it an MPS catalog number. However, any hopes of releasing it during Evans’ lifetime were dashed when Brunner-Schwer and Keane had an argument regarding a later Evans MPS album, “Symbiosis”. As late as 1982, MPS still had tentative plans to release the recording, but the album was never issued and with the deaths of Evans, Keane, and Brunner-Schwer, the session was basically forgotten. In 2013, Zev Feldman rediscovered the recording and the entire session was recently issued on the 2-CD set “Some Other Time” (Resonance 2019). The album package includes notes by Feldman, Marc Myers and Friedhelm Schulz, along with in-depth interviews of Gomez and DeJohnette.

eager to make a recording similar to the “Exclusively for my Friends” dates which Oscar Peterson had recorded in the MPS studio. Whatever the reason, the Evans trio recorded 94 minutes of music on June 20. At some point, Brunner-Schwer sequenced an LP and assigned it an MPS catalog number. However, any hopes of releasing it during Evans’ lifetime were dashed when Brunner-Schwer and Keane had an argument regarding a later Evans MPS album, “Symbiosis”. As late as 1982, MPS still had tentative plans to release the recording, but the album was never issued and with the deaths of Evans, Keane, and Brunner-Schwer, the session was basically forgotten. In 2013, Zev Feldman rediscovered the recording and the entire session was recently issued on the 2-CD set “Some Other Time” (Resonance 2019). The album package includes notes by Feldman, Marc Myers and Friedhelm Schulz, along with in-depth interviews of Gomez and DeJohnette.

With no imminent release in sight, Evans was apparently feeling experimental at this session. There is an interesting mix of solo, duo and trio tracks (DeJohnette says this was Evans’ idea, although it was rather unusual for an Evans album) and Gomez notes that many of the songs were not regular parts of the group’s repertoire. There were no dips into the pop-rock songbook—those would come years later—but the opening track of the second disc was a fairly recent pop hit (written within the style of the Great American Songbook by Andre and Dory Previn) called “You’re Gonna Hear from Me”. Elsewhere, standards ruled the day, with an engaging version of “You Go to My Head” leading off the album proper. The same push-and-pull of the rhythmic flow that appeared on the Montreux stage is present in the Villigen studio, and the greater presence of the MPS recording makes it easier to hear how each member of the trio contributes to the overall sound. “Very Early” weaves between duple and triple meters like the live version of “Prince”, but the groove seems to pull apart at places. DeJohnette lays out on “What Kind of Fool Am I” and “I’ll Remember April”, and it’s hard to determine why: Evans and Gomez essentially play in the same style as they did in the trio, and there is plenty of room for the drums to enter into the conversation.

The trio version of “My Funny Valentine” will be a shock to those listeners familiar with the up-tempo duo setting recorded by Evans and guitarist Jim Hall in 1959. Here, Evans sticks to the traditional slow tempo even when his improvisations lean toward a faster pulse. There’s one spot where DeJohnette jumps into double-time, but rather than joining in, Evans continues the rhythmic dichotomy by dragging his lines against DeJohnette’s pulse. Gomez steals the show on the duo version of “Baubles, Bangles and Beads” with a stunning bass line that keeps the harmonic and rhythmic pulse intact while adding impressive filigrees between the beats. “Turn out the Stars” is a set highlight, with the trio using shifting dynamics to add intensity to this superb Evans composition. A light-hearted swinging duet version of “It Could Happen to You” provides necessary relief, as does the lilting trio setting of “In a Sentimental Mood” (even though DeJohnette’s forceful cymbals add an unexpected edge to the latter performance). “These Foolish Things” may be the best of the album’s duets, mainly because Evans and Gomez play in a sustained manner which fills the spaces, leaving no room for additional instruments. Indeed, that sustained style continues on the first disc’s closer, “Some Other Time” and DeJohnette’s contributions are limited to occasional brushes on the snare and a few well-placed cymbal rolls.

The first disc of the Resonance set represents Brunner-Schwer’s original selections for issue. However, the tracks on the second disc are all superbly played, and except for the two takes abruptly ended by Evans, any of the selections might have been included on the aborted MPS issue. The two versions of “You’re Gonna Hear from Me” each feature a unique loping swing (with superb interplay on the “master” and fine recurring descending lines on the “alternate”). Played at a slightly slower tempo than at Montreux, “Walkin’ Up” retains its compelling intensity even when opened up for an extra minute-and-a-half of solos. Gomez plays another resourceful bass line on the trio take of “Baubles” while Evans and DeJohnette seem to have their own conversation going. The usually harmonically astute Evans fumbles through a solo version of “It’s All Right with Me”, missing a turnaround and not sounding too sure of the melody. About three minutes in, his frustration starts to show as he throws in a series of Monkish dissonances before giving up altogether. The trio version of “What Kind of Fool” has very energetic swing as well as percussive lines from Evans, but apparently the pianist wasn’t too happy with the results and he closes the take with a corny (and completely unexpected) “shave and a haircut” coda. The rhythmic energy of the trio returns in a hard-swinging version of “How About You”, while the time surges and relaxes through “On Green Dolphin Street”. “Wonder Why” had turned up on Evans’ 1963 live LP from Shelly’s Manne Hole and on a Village Vanguard set from 1967, but the Villigen recording was his last recording of the tune. It’s a shame: the 1968 trio engages the tune thoroughly, jumping on the melody’s unique accents, and giving the entire performance a delightful rhythmic bounce. Before closing with the “alternate” of “You’re Gonna Hear”, the album includes another gem: a sparsely chorded solo version of “Lover Man” that reaches into the core of the song, both in the melody and the unheard lyrics.

On June 22, the trio performed a concert at the VARA Studio 8 in Hilversum, Holland for NRU Radio. The tape’s existence had been documented for years, but it was not until a few months after the release of the MPS recordings that Zev Feldman acquired them for an authorized CD/LP release. The album, “Another Time” (Res onance 2031) presents the entire 48-minute Hilversum concert in stunning fidelity. Evans plays a superbly tuned and voiced piano, and the sounds of Gomez’ bass and DeJohnette’s drums are captured with close-miked presence. The mix makes the listener feel like he is in the middle of the group, with Evans to the left, Gomez to the right, and DeJohnette directly in front. The concert opens with the last tune from the MPS set, “You’re Gonna Hear from Me”, played at a slightly faster tempo with increased drive. Both Gomez and DeJohnette commented about the energy of the live audience, and that quality certainly translates into the music. Gomez leans into the ground beat as he walks, and DeJohnette sounds more animated than in the studio. On “Very Early”, DeJohnette’s brushwork is exquisite, and the groove locks in, despite the cross-rhythms from Evans and Gomez. Evans had recorded versions of “Who Can I Turn To?” and “Alfie” with earlier versions of his trio, but the Hilversum concert tapes contain the first recordings of those songs by this trio. Evans opens “Turn” with a rubato solo introduction, and when the rest of the group enters, they allow the time to ebb and flow through the remainder of the melody chorus. Once Gomez starts soloing, DeJohnette subtly moves into straight time. Gomez’ phrase lengths on this solo are more interesting than the actual notes—he doesn’t create a true improvised melody, but the shapes of the phrases are astounding. Evans plays a fairly short solo, but the passage is notable for the incredible intensity generated by the trio. “Alfie” plays in a broad, slow tempo, and each member of the trio finds unique ways to sub-divide the beats. Without a explicitly stated ground beat, the various rhythmic ideas interact freely like the elements of an Alexander Caulder mobile.

onance 2031) presents the entire 48-minute Hilversum concert in stunning fidelity. Evans plays a superbly tuned and voiced piano, and the sounds of Gomez’ bass and DeJohnette’s drums are captured with close-miked presence. The mix makes the listener feel like he is in the middle of the group, with Evans to the left, Gomez to the right, and DeJohnette directly in front. The concert opens with the last tune from the MPS set, “You’re Gonna Hear from Me”, played at a slightly faster tempo with increased drive. Both Gomez and DeJohnette commented about the energy of the live audience, and that quality certainly translates into the music. Gomez leans into the ground beat as he walks, and DeJohnette sounds more animated than in the studio. On “Very Early”, DeJohnette’s brushwork is exquisite, and the groove locks in, despite the cross-rhythms from Evans and Gomez. Evans had recorded versions of “Who Can I Turn To?” and “Alfie” with earlier versions of his trio, but the Hilversum concert tapes contain the first recordings of those songs by this trio. Evans opens “Turn” with a rubato solo introduction, and when the rest of the group enters, they allow the time to ebb and flow through the remainder of the melody chorus. Once Gomez starts soloing, DeJohnette subtly moves into straight time. Gomez’ phrase lengths on this solo are more interesting than the actual notes—he doesn’t create a true improvised melody, but the shapes of the phrases are astounding. Evans plays a fairly short solo, but the passage is notable for the incredible intensity generated by the trio. “Alfie” plays in a broad, slow tempo, and each member of the trio finds unique ways to sub-divide the beats. Without a explicitly stated ground beat, the various rhythmic ideas interact freely like the elements of an Alexander Caulder mobile.

In the notes to “Another Time”, Gomez reveals that the Montreux version of “Embraceable You” was the first time he had played that piece with the trio, and that he wasn’t particularly comfortable with having a bass feature in the first place. However, he acknowledges that both the Montreux and Hilversum recordings are good renditions. The Hilversum version is much relaxed than Montreux, with a slower tempo to start, and with the speed changes clearly designated. The version of “Emily” which follows alternates between graceful and energetic grooves, with the two moods combining in the final chorus. “Nardis” was a piece that changed from night to night. Although the trio recorded a stunning version at Montreux a week earlier, the Hilversum version is remarkable in its own right. From the quiet opening of Gomez’ unaccompanied solo through an active three-way dialogue during Evans’ improvisation, to DeJohnette’s powerful (yet highly inventive) drum solo, the group amazes the listener with the varied resources it brings to this Miles Davis composition. In contrast to the flowing groove the trio found two days earlier on “Turn out the Stars”, the Hilversum rendition is performed in a very stiff and unyielding tempo, with Evans playing very deliberate dotted-eighth/sixteenth note patterns during his solo. “Five”, the traditional Evans set closer, fulfills that obligation here, although the version here sounds like a top spinning out of control. The tempo is ridiculously fast and the three musicians don’t fully coalesce until the beginning of DeJohnette’s solo. There’s also a quote of “Oleo” in the out-chorus, which makes me think that this piece was thoroughly rehearsed. Sometimes it takes a lot of work to create organized chaos!

The trio’s style transformed during its month-long residency at Ronnie Scott’s in London. While there, all three members told Les Tomkins that they wanted to create a more aggressive approach to the music, and the existing recordings made by DeJohnette (now issued as the Resonance CD/LP, “Live at Ronnie Scott’s“) display considerable changes from the Montreux, Villigen and Hilversum recordings made only a month earlier. The loping gait of “You’re Gonna Hear from Me” becomes a confident strut at Ronnie Scott’s, with DeJohnette on sticks playing short snare rolls and splashy cymbal fills, while Gomez creates a busy counterpoint to Evans’ piano. On “Yesterdays”, DeJohnette’s insistent hi-hat accents push Evans into more aggressive waters, and the group’s energetic rendition of “Waltz for Debby” shakes loose all of the song’s cobwebs, but loses all of its charm as well. Without access to the original tapes, it’s hard to make guesses about specific details, but aural and musical evidence suggest that the recordings were made on at least two different dates. There are tracks (such as the trio version of “Quiet Now”) where the group sounds much as they did earlier in the summer. In other places, Evans cuts his own solos short, as if he is reluctant to compete with his sidemen in such aggressive surroundings. However, many of the tracks show the trio embracing the three-way dialogue that had been a goal of the Evans trios since the classic Evans-Scott LaFaro-Paul Motian edition of 1959-1961. The Resonance set does not offer a “missing link” between the (relatively) sedate European recordings and the highly aggressive Village Vanguard tracks discussed below, but it clearly shows a dramatic change in the aesthetics of this trio.

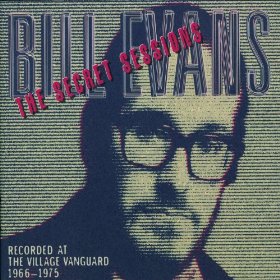

The Vanguard recordings are part of the 8-CD box set “The Secret Sessions” (Milestone 4421), and as the name implies, the music was recorded surreptitiously. Evans fan and amateur pianist Mike Harris snuck a reel-to-reel  recorder and a microphone into the front row of the Vanguard—on several occasions, no less!— and captured the Evans trio performances. The August 23 recordings are the only Vanguard performances with DeJohnette behind the drums. He is a primal force on these tracks and his sound dominates the recordings. It would be tempting to say that DeJohnette is playing too loud and is overbearing, but we must remember that these are amateur recordings, and drums pick up better than any other instrument on non-professional microphones. DeJohnette states unequivocally that Evans never consulted nor complained about the sound or volume of his drums. On the contrary, Evans seemed encouraged by the lively interplay. However, there is no doubt that DeJohnette plays very powerfully on these tracks. Although the tunes—“My Man’s Gone Now”, “Who Can I Turn To?”, “Polka Dots and Moonbeams” and “Emily”—could all qualify as ballads, DeJohnette uses sticks more than brushes throughout and on “My Man’s Gone Now”, he uses his mallets on the floor tom to great dramatic effect.

recorder and a microphone into the front row of the Vanguard—on several occasions, no less!— and captured the Evans trio performances. The August 23 recordings are the only Vanguard performances with DeJohnette behind the drums. He is a primal force on these tracks and his sound dominates the recordings. It would be tempting to say that DeJohnette is playing too loud and is overbearing, but we must remember that these are amateur recordings, and drums pick up better than any other instrument on non-professional microphones. DeJohnette states unequivocally that Evans never consulted nor complained about the sound or volume of his drums. On the contrary, Evans seemed encouraged by the lively interplay. However, there is no doubt that DeJohnette plays very powerfully on these tracks. Although the tunes—“My Man’s Gone Now”, “Who Can I Turn To?”, “Polka Dots and Moonbeams” and “Emily”—could all qualify as ballads, DeJohnette uses sticks more than brushes throughout and on “My Man’s Gone Now”, he uses his mallets on the floor tom to great dramatic effect.

In closing this section of his Evans biography, “How My Heart Sings” (Yale), Peter Pettinger claims that had DeJohnette not received the call from Miles Davis, he might have stayed with Evans much longer. Perhaps so, but as it stands—with DeJohnette leaving Evans within weeks of the August Vanguard gig—this edition of the Bill Evans trio may have already accomplished a primary goal: an expansion of the basic trio sound and a genuine reflection of the troubled times. Even though Evans never aspired to this powerful style again, the 1968 trio with DeJohnette created a small but potent collection of important music.