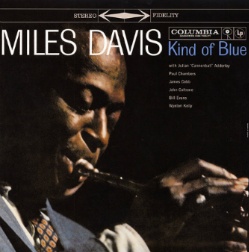

Some nights, you just have to listen to “Kind of Blue”.

Some nights, you just have to listen to “Kind of Blue”.

Around 11:00 last night, I typed that sentence into my Facebook status. An hour earlier, I’d come home from a choir/orchestra dress rehearsal. My legs and feet were tired from excessive standing, my voice was worn out after hours of high-register singing, but my mind was still active, and I wondered if the bottle of Pepsi I had consumed during rehearsal would prevent me from going to sleep. I searched YouTube for a temporary diversion, and I found a hi-resolution remaster of “Kind of Blue”. Perfect. While I doubt that the recording I heard contained the ultimate high-fidelity it promised, the music by Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb comforted me like a warm blanket, and transported me by the sheer beauty of the music. Just like a child who asks a parent to repeat a well-known fairy tale as a bedtime story, or an adult who revisits a movie they’ve seen dozens of times, “Kind of Blue” has the power to revitalize us, long after we’ve learned all of its lessons.

It is no accident that this particular album is the highest-selling recording in jazz history. Even when discounting the multiple copies jazz fans have purchased since its original release in 1959 (LP, CD, CD speed-corrected remaster, 180g half-speed remastered vinyl, mono versions, surround sound, hi-res, reissues, et.al.), the fact remains that the sales numbers credited to “Kind of Blue” far outnumber the group of straight-ahead jazz fans. Although “Kind of Blue” has converted many listeners into jazz fans, you don’t have to make that leap in order to enjoy the music. My friend and colleague Mick Carlon is a public school teacher in Massachusetts. He requests that every one of his middle school students buy a copy of “Kind of Blue” and he offers to buy back the disc from anyone who doesn’t love the music. In 30 years, only three students have ever asked for the reimbursement. The kids that kept the album may not have purchased any other iconic jazz albums, but I’m sure that some of them keep the album around for the same sort of listening experience which I had last night.

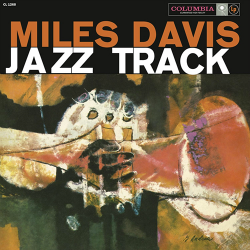

Every jazz history textbook states that “Kind of Blue” was an important album because of its use of modal improvisation. Of course, that statement is absolutely true, but that does not explain the album’s phenomenal popular and artistic success. To my ears, the modes were the means to an end; “Kind of Blue” would have been just another historical milepost if not for the musicians’ collective aesthetic pursuit of beauty. Had any other jazz album ever focused on poetic improvised lines in the manner of “Kind of Blue”? “Charlie Parker with Strings” and “Clifford Brown with Strings” had set the bar, but Davis and Evans raised that standard both on “Kind of Blue” and its immediate studio predecessor, the second side of “Jazz Track”. “Jazz Track” was an intriguing album: the first side featured excerpts from Davis’ improvised score to the Louis Malle film “Elevator to the Gallows”. On that soundtrack, Davis experimented with the modal forms which he had previously used on “Milestones” and what would become the major structural device on “Kind of Blue”. But the French soundtrack was a one-off project created in a single night; when Davis returned to the States, he formed a new sextet—the same group that would create “Kind of Blue”—and he tried to find a way to create intense performances which depended on dramatic statements from the soloists. The band’s versions of “Green Dolphin Street”, “Stella by Starlight” and “Fran-Dance” met the objectives with spectacular results. Then the band got edgy and wanted to swing. Davis turned around and said “Love for Sale” and kicked off a medium tempo. The energetic release of the rhythm section and the exuberance of the solos by Davis, Adderley and Evans transformed the mood. Coltrane experimented with overlaying modal ideas on top of the chordal structure, and he missed some of the changes along the way. Some have blamed Coltrane for the track remaining unissued, but the simple fact is that “Love for Sale” just didn’t fit—in more ways than one. Not only was the feel of “Love for Sale” completely different from the other tracks; at nearly 12 minutes, it was just too long to fit onto a single LP side with the other 20 minutes of music recorded that day. So “Love for Sale” remained in the Columbia vaults until 1972, when it appeared on a compilation called “Black Giants”.

new sextet—the same group that would create “Kind of Blue”—and he tried to find a way to create intense performances which depended on dramatic statements from the soloists. The band’s versions of “Green Dolphin Street”, “Stella by Starlight” and “Fran-Dance” met the objectives with spectacular results. Then the band got edgy and wanted to swing. Davis turned around and said “Love for Sale” and kicked off a medium tempo. The energetic release of the rhythm section and the exuberance of the solos by Davis, Adderley and Evans transformed the mood. Coltrane experimented with overlaying modal ideas on top of the chordal structure, and he missed some of the changes along the way. Some have blamed Coltrane for the track remaining unissued, but the simple fact is that “Love for Sale” just didn’t fit—in more ways than one. Not only was the feel of “Love for Sale” completely different from the other tracks; at nearly 12 minutes, it was just too long to fit onto a single LP side with the other 20 minutes of music recorded that day. So “Love for Sale” remained in the Columbia vaults until 1972, when it appeared on a compilation called “Black Giants”.

The rest of the musicians may have forgotten about “Love for Sale”, but Davis remembered the lessons of that session. Certainly, he realized that modal improvisation would support the type of intense improvisations that he wanted to hear from his band. In a 1958 interview with Nat Hentoff, Davis said of modal playing, When you go this way, you can go on forever. You don’t have to worry about changes and you can do more with the line. “Love for Sale” was actually a very good performance (Coltrane not withstanding), but it swung too hard to maintain the dramatic mood. All of these things were probably on Davis’ mind when he and Bill Evans began their collaboration on “Kind of Blue”. Evans had left Davis’ band by October 1958, but Davis—who was obviously trying to capture this sound before it completely disappeared—realized that Evans’ impressionistic approach was a key ingredient of his new concept.

Rather than playing familiar melodies, Davis wanted his listeners to focus on the improvisations. Thus, the tunes were designed to be nearly anti-melodic. “Flamenco Sketches” has no discernible melody at all, and those who cover this track generally play some version of Davis’ opening solo as the melody chorus (Bob Belden once suggested creating a melodic line from Davis’ solos on the existing five takes of this track). Similarly, “Blue in Green”—written by Evans from a pair of chords suggested by Davis—has an opening theme which sounds like an improvisation. The album’s first two tracks, “So What” and “Freddie Freeloader” feature the same exact main motive, played at the same pitches on both tracks. Finally, “All Blues” offers the barest sketch of melody which floats over a 6/8 blues progression, and offers only one small point of melodic tension.

In subsequent years, millions of musicians and fans have memorized those melodic scraps, but more importantly, we have memorized the solos on those tracks (We’ve even remembered what happens in the background: who doesn’t mime Cobb’s brilliant cymbal crash at the beginning of Davis’ solo on “So What”?). In creating memorable solos, the Miles Davis Sextet exceeded all expectations. Although they had not seen this music prior to the recording sessions, they seemed to understand the import of this music, and they created solos that defied the limits of time. The open-ended quality of the modes allowed the musicians to create long, exquisite lines, but beyond that, the improvisations seemed uniquely personal and intimate, so that hearing them played by other musicians appeared less genuine. While the soloists of this band recorded many tender, heart-rending improvisations in subsequent years, it is as if they all hit their peaks on these two recording dates in 1959. Beauty was sought and discovered on those days, and the result was a masterpiece for the ages. That might sound like an overstatement, but if “Kind of Blue” was merely a historical landmark, would it be the record we reach for at the end of a long, exhausting day?

I have linked to versions of the original albums above; however, for those who would like to have all of this music together, seek out the 2-CD 50th Anniversary Legacy edition, which includes all of the issued “Kind of Blue” masters and alternates, plus the complete “Green Dolphin Street”/“Stella by Starlight”/“Love for Sale” session.