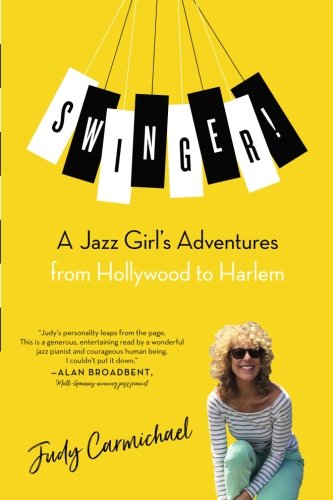

One of jazz’s unique attributes is the coexistence of styles. No matter what genre attracts a musician, they will find colleagues who will want to play with them, and (eventually) audiences who will pay to hear the music. Still, the appearance of the young, blonde, and stunningly attractive stride pianist Judy Carmichael was a shock to musicians and fans alike. Growing up in the less-than-glamorous Southern California town of Pico Rivera, Carmichael—then known as Judy Hohenstein—learned piano by ear, and mastered Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” at age 11 to win a challenge from her paternal grandfather, who gave her $50 for her efforts (Grandfather then withdrew his offer of $100 to learn “Cannonball Rag”!). Years later, a friend gave Judy a cassette copy of the Bennie Moten band’s recordings with their pianist, Bill Basie. Basie’s brilliant showcase on “Prince of Wails” made the twenty-something a dedicated stride piano fan, as it helped to realize the way she could combine improvisation with the ragtime she had loved since childhood. Carmichael’s recounting of this eureka moment is one of the highlights of her recently published memoir, “Swinger!: A Jazz Girl’s Adventure” (C & D Productions).

One of jazz’s unique attributes is the coexistence of styles. No matter what genre attracts a musician, they will find colleagues who will want to play with them, and (eventually) audiences who will pay to hear the music. Still, the appearance of the young, blonde, and stunningly attractive stride pianist Judy Carmichael was a shock to musicians and fans alike. Growing up in the less-than-glamorous Southern California town of Pico Rivera, Carmichael—then known as Judy Hohenstein—learned piano by ear, and mastered Scott Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag” at age 11 to win a challenge from her paternal grandfather, who gave her $50 for her efforts (Grandfather then withdrew his offer of $100 to learn “Cannonball Rag”!). Years later, a friend gave Judy a cassette copy of the Bennie Moten band’s recordings with their pianist, Bill Basie. Basie’s brilliant showcase on “Prince of Wails” made the twenty-something a dedicated stride piano fan, as it helped to realize the way she could combine improvisation with the ragtime she had loved since childhood. Carmichael’s recounting of this eureka moment is one of the highlights of her recently published memoir, “Swinger!: A Jazz Girl’s Adventure” (C & D Productions).

As “Swinger!” is not a standard autobiography, Carmichael’s narrative jumps around in time. She opens with her 2003 diagnosis of cervical cancer, then jumps back fifty years to tell of her parents and her childhood. It seems obvious that the book was not written in sequence, and there are several head-shaking moments where Carmichael seems to introduce a subject which was actually discussed in detail twenty or thirty pages earlier! The narrative stays fairly chronological for the first third of the book, but the problems start to appear after Carmichael writes about recording her first album “Two-Handed Stride”. Carmichael made the album in 1980 without a record label’s support (much rarer then than now) and it took some time before Progressive Records agreed to issue and distribute the recording. Carmichael includes a flurry of anecdotes relating to her early meetings with jazz legends. The stories seem to appear in random order, as she tells us that this situation happened before (or just after) “Two-Handed Stride” was released. Authors have used the non-linear time approach for years—most notably Kurt Vonnegut in “Slaughterhouse-Five”—but Carmichael’s use of the technique is awkward and jarring.

Still, Carmichael is an engaging storyteller, and once the reader accepts the narrative jumps, the memoir is both entertaining and enlightening. Trust me: you will never think of the song “I Found a New Baby” in the same way after reading Carmichael’s tale of a Chinese interpreter who translated the title quite literally. She also relates a secret about getting through airport security with potentially embarrassing items in her carry-on. And just to offer a sample of her witty writing style, here’s a brief passage regarding a trip to the ancient Greek city of Ephesus:

Everyone visited Ephesus: Cleopatra, Paul, the Virgin Mary, Sting, Ray Charles—all the biggies. This is where Paul wrote his letter to the Ephesians, discouraging the selling of idols. Idol-selling continues to this day, of course. I just saw Nunzilla, a fire-breathing wind-up nun doll, in our local toy store yesterday, so obviously no one listened to Paul. It’s so easy to ignore a letter.

Not everything in Carmichael’s book is light and cheery. While her family seemed outwardly normal and happy, it was highly dysfunctional. Her father hid his two decades of alcoholism from Carmichael until she was in her twenties, and her mother only seemed happy when the spotlight was on her. Carmichael’s father’s condition grew worse and worse, and he was homeless when he took his own life. A few years later, Carmichael’s mother was diagnosed with cancer after the disease had spread throughout her body. Carmichael’s descriptions of her last visits with both parents, and her discovery of their deaths is chilling and unforgettable. What becomes apparent is that Carmichael was in the same situation faced by many artists: she received more encouragement from her peers and colleagues than she ever did from her family (and this, from parents who—at least on the surface—were supportive of her career choice). As with her eventual tales of her own cancer recovery, Carmichael drops in light-hearted stories about her parents to lighten the mood. However, anyone who has experienced similar traits in their own family will share Carmichael’s deep emotional pain.

Elsewhere in the book, Carmichael addresses life as a working musician, her occasional appearances as a sideperson, her responses to fans who discover that she has remained unmarried, her experiences playing on cruise ships, her friendships with famous people (not all from the jazz world) and her work as a radio host and interviewer (her long-running series “Jazz Inspired” appears on Sirius XM radio and on iTunes). We read about a wide variety of characters ranging from a stuffed toy character from “Where the Wild Things Are” to the all-too-amorous Vice President of Brazil. While musicians might wish for more details on Carmichael’s influences and style, for the general public, “Swinger!” is a delightful journey through the life of a fascinating woman.