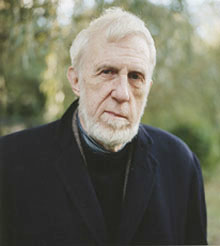

In classical vocal music, ac companists are a steadying force. They are expected to play a written part exactly the same way every time, and to stay attuned to the needs of the vocalist, providing help whenever the singer goes astray. Since jazz contains significant amounts of improvisation, the role of a jazz accompanist does not require the exact repetition of the harmonic structure—voicings and rhythms can change from performance to performance—but the accompanist still takes a secondary role to the vocalist, and the accompanist is expected to come to the rescue in case of a vocal emergency. For over 50 years, pianist Ran Blake (left) has taken an alternative approach. His 1962 LP with Jeanne Lee, “The Newest Sound Around” was a revelation in the sheer independence of Blake’s piano lines. Starting with Lee—and continuing through the present—Blake expects his vocalists to know their music so well that they find their way without his assistance. As vocalist Sara Serpa noted a few years ago, Ran is not a typical piano player who will follow the rules. He might change the tempo or the key right in the middle of the song and you have to be really aware of what is going on. It’s always challenging, thinking that you never know what will happen next. To be sure, only the most advanced vocalists can successfully work with Blake. The CDs reviewed below feature Blake in duet settings with two vocalists who are both progressive but possess significantly different styles.

companists are a steadying force. They are expected to play a written part exactly the same way every time, and to stay attuned to the needs of the vocalist, providing help whenever the singer goes astray. Since jazz contains significant amounts of improvisation, the role of a jazz accompanist does not require the exact repetition of the harmonic structure—voicings and rhythms can change from performance to performance—but the accompanist still takes a secondary role to the vocalist, and the accompanist is expected to come to the rescue in case of a vocal emergency. For over 50 years, pianist Ran Blake (left) has taken an alternative approach. His 1962 LP with Jeanne Lee, “The Newest Sound Around” was a revelation in the sheer independence of Blake’s piano lines. Starting with Lee—and continuing through the present—Blake expects his vocalists to know their music so well that they find their way without his assistance. As vocalist Sara Serpa noted a few years ago, Ran is not a typical piano player who will follow the rules. He might change the tempo or the key right in the middle of the song and you have to be really aware of what is going on. It’s always challenging, thinking that you never know what will happen next. To be sure, only the most advanced vocalists can successfully work with Blake. The CDs reviewed below feature Blake in duet settings with two vocalists who are both progressive but possess significantly different styles.

Originally from Mumbai, India, Christine Correa teaches Jazz Performance at Columbia University. Like Jeanne Lee, she has a deep interest in poetry, and she has performed settings of modern poets like Frank Carlber g, Nicholas Urle and Steve Grover. Her album with Blake, “The Road Keeps Winding” (Red Piano 4415) is the duo’s second volume of a tribute to Abbey Lincoln. In retrospect, it’s odd that Lincoln never made an album with Blake, but Correa’s renditions of Lincoln’s songs give an approximation of what a Lincoln/Blake album might have sounded like. From the opening track, “Straight Ahead”, Correa brings out the edgy, in-your-face Lincoln style, without sounding like a copy. Blake’s opening accompaniment is almost traditional—he even plays a few notes of the melody with Correa!—but before long, he’s exploring new directions, adding little solo lines and opaque impressionistic chords. Correa’s powerful vocal on “The River” is sung over an eerie buzzing drone, and a sole maraca provides the only other accompaniment. Correa also tempers her vocal tone over the course of the album, sounding quite tender on two songs by R.B. Lynch, “When Autumn Sings” and “Love Lament”. Many contemporary singers have covered Lincoln’s original, “Throw It Away”, and it appears in two separate versions on this albums. Ironically, Blake plays them both as piano solos! The first version floats in time, as Blake explores the lowest registers of the piano; the second is in fairly strict time, and while it includes some murky chord voicings, it is essentially a straight-forward improvisation on the song. The album’s highlight may be “Midnight Sun”, a song with a descending vocal line that can be fiendishly difficult to keep in tune. Trusting Correa to negotiate the tricky passage on her own, Blake plays ascending chord patterns against the line at the beginning, and then finds a number of surprising ways to provide counterpoint to the vocal line. Yet beyond the trickery lays a deep understanding of the song, and the performance here ranks as one of the finest made of this well-worn standard.

g, Nicholas Urle and Steve Grover. Her album with Blake, “The Road Keeps Winding” (Red Piano 4415) is the duo’s second volume of a tribute to Abbey Lincoln. In retrospect, it’s odd that Lincoln never made an album with Blake, but Correa’s renditions of Lincoln’s songs give an approximation of what a Lincoln/Blake album might have sounded like. From the opening track, “Straight Ahead”, Correa brings out the edgy, in-your-face Lincoln style, without sounding like a copy. Blake’s opening accompaniment is almost traditional—he even plays a few notes of the melody with Correa!—but before long, he’s exploring new directions, adding little solo lines and opaque impressionistic chords. Correa’s powerful vocal on “The River” is sung over an eerie buzzing drone, and a sole maraca provides the only other accompaniment. Correa also tempers her vocal tone over the course of the album, sounding quite tender on two songs by R.B. Lynch, “When Autumn Sings” and “Love Lament”. Many contemporary singers have covered Lincoln’s original, “Throw It Away”, and it appears in two separate versions on this albums. Ironically, Blake plays them both as piano solos! The first version floats in time, as Blake explores the lowest registers of the piano; the second is in fairly strict time, and while it includes some murky chord voicings, it is essentially a straight-forward improvisation on the song. The album’s highlight may be “Midnight Sun”, a song with a descending vocal line that can be fiendishly difficult to keep in tune. Trusting Correa to negotiate the tricky passage on her own, Blake plays ascending chord patterns against the line at the beginning, and then finds a number of surprising ways to provide counterpoint to the vocal line. Yet beyond the trickery lays a deep understanding of the song, and the performance here ranks as one of the finest made of this well-worn standard.

While Correa’s edgy voice seems to speak of hard times and real-world experience, Sara Serpa’s light voice sounds pure and innocent. Yet, Serpa’s astonishing flexibility and musical imagination make her one of the most remarkable vocalists working today. Her partnership with Blake started when she was one of hi s students at the New England Conservatory. “Kitano Noir” (Sunnyside 1362) is their third album together, and in contrast to the Correa disc, Blake’s voicings seem lighter to match Serpa’s voice. A few of the tracks are remakes of songs that they’ve recorded on their earlier albums. However, the fertile creativity of both vocalist and pianist ensure that the current versions are considerably different that their earlier incarnations. For example, “When Sunny Gets Blue” opened the duo’s first album, “Camera Obscura” (Inner Circle 15) and that recording had a clearly delineated vocal and a few surprising note choices. The new version finds Serpa taking a looser approach to the underlying tempo, and features some of Serpa’s most daring harmonic inventions on record. However, the best moments of this recording occur on the new pieces, including Serpa’s stunning a cappella version of “Mãe Preta” and Blake’s “Indian Winter” (which features delightful Monkish interplay between Serpa and Blake). Blake creates a dense reharmonization of “Mood Indigo” which enhances Serpa’s simultaneously heartfelt and exploratory reading. “Round Midnight” gets a similar treatment, but the closing chorus contains a fascinating abstraction of the familiar introduction with both Serpa and Blake playing pivotal roles in its presentation. The whimsical version of Chris Connor’s “Moonride” that appears between these two jazz classics benefits both from Blake’s tongue-in-cheek accompaniment and Serpa’s charming Portuguese accent. As on the Correa album, Blake has a few solo features, and this album includes a dramatic version of “Good Morning Heartache”.

s students at the New England Conservatory. “Kitano Noir” (Sunnyside 1362) is their third album together, and in contrast to the Correa disc, Blake’s voicings seem lighter to match Serpa’s voice. A few of the tracks are remakes of songs that they’ve recorded on their earlier albums. However, the fertile creativity of both vocalist and pianist ensure that the current versions are considerably different that their earlier incarnations. For example, “When Sunny Gets Blue” opened the duo’s first album, “Camera Obscura” (Inner Circle 15) and that recording had a clearly delineated vocal and a few surprising note choices. The new version finds Serpa taking a looser approach to the underlying tempo, and features some of Serpa’s most daring harmonic inventions on record. However, the best moments of this recording occur on the new pieces, including Serpa’s stunning a cappella version of “Mãe Preta” and Blake’s “Indian Winter” (which features delightful Monkish interplay between Serpa and Blake). Blake creates a dense reharmonization of “Mood Indigo” which enhances Serpa’s simultaneously heartfelt and exploratory reading. “Round Midnight” gets a similar treatment, but the closing chorus contains a fascinating abstraction of the familiar introduction with both Serpa and Blake playing pivotal roles in its presentation. The whimsical version of Chris Connor’s “Moonride” that appears between these two jazz classics benefits both from Blake’s tongue-in-cheek accompaniment and Serpa’s charming Portuguese accent. As on the Correa album, Blake has a few solo features, and this album includes a dramatic version of “Good Morning Heartache”.

Both of these albums show that vocal/piano duets can be equal partnerships, rather than an uneven match between singer and accompanist. Blake’s uncompromising style allows his contributions to come forward, even in the middle of a vocal chorus. By asserting his unique approach, Blake becomes an integral part of the vocal/piano duet, and by insisting that singers use their ears to guide them through performances, he makes those vocalists stronger musicians (The best recordings I’ve heard by Jeanne Lee, Dominique Eade and Sara Serpa have all been with Blake). At 80, Blake is still a powerful creative force and one of jazz’s true masters. If anything, he seems to be recording more these days, and that’s good news for everyone involved: Blake certainly deserves greater recognition for his accomplishments, and these recordings offer abundant proof of how his accompaniments can enrich the performances of talented vocalists. Yet it may be the listeners who benefit most of all, as they witness the extraordinary range of music that can be produced by a pair of adventurous souls.